11 Tips on How to Apply for a Fellowship

Published in Astronomy

If you are looking for a job, you will soon realize that there are less jobs in research than people applying for them. After trying all the regular post-doc calls without luck, you may easily find yourself flirting with the idea of a Fellowship. Or, as happened to many of us, someone may express interest in working with you – with the massive caveat that you should “find your own funding” by way of a Fellowship.

But how can you do that? How should you even start?

Here are 11 tips that I wish someone told me when I was in your shoes.

1. Don’t try to write a fellowship application on your own.

Writing a fellowship application is a skill: you have to learn the tricks. It’s as difficult as learning how to write a paper. Yet it’s not like writing a paper. It’s a whole new skill set that you have to master.

So don’t think you can do it all alone. (I have. Big mistake.)

Seek out support. Preferably a whole department or office (at your prospective host institute) specializing in grant writing. They will be happy to assist you: this is their job. Asking for their help is not an admission of being slow-witted! It is a sign that you are ready to learn.

Trying it without help will probably not lead to success, and thus it may destroy your self-confidence. And you need your self-confidence if you are going to do this.

2. Expect a (potentially successful) fellowship application to take a long, a really long time to write.

In my case, it was well over 3 month of FTE (full-time-equivalent). Yes. I’m serious. Some people may be able to do it in less time, and it’s really up to you, but in general you better expect that it will take long.

According to a small study I have conducted (collecting the self-reported responses of 50 fellowship holders), 2/3rd of the people who got a fellowship had spent more than 1 month of FTE on it [1].

So to stand a chance, you should probably consider allocating a comparable amount of effort to it too.

This also means that your supervisor needs to get on board. They should understand why you’re not making too much progress during these months in your research project (cf. my point #9). But as I said, it’s a skill. It simply takes time to learn all the tricks of creating a competitive application.

The good news is, it gets better, if slowly. For example, you can reuse some parts of an old, failed application when starting a new one; so even a rejected application is not a complete waste of time.

3. You’ll have to learn how to sell. Oh, and it may hurt.

Prepare yourself psychologically that your first draft of ideas, the one that you worked on for weeks, put your whole heart in, developed and cherished because it’s your first independent science project, will be crushed. Criticized. Picked apart. You’ll need to change it, and change it again, and again.

Not necessarily because they are bad ideas, but because they are not (or at the very least, not yet read like) what grant juries wish to give money to.

You’ll learn how to sell yourself. Yeah.

That may sound scary now, or even immoral (after all, science should be driven by pure, objectively decided values and directions – well, it’s not, or not always) but that’s how it is. Unfortunately, if you cannot stomach this, there is a very limited chance you succeed in today’s academic world. (And your chance is already quite limited, let’s be honest*.)

*Pssst. I’m not saying it’s a good system, or that I like it. If anyone wishes to organize a grassroot movement of PhDs and post-docs, unionize them or something, I would support it! It would be great to change the system, unite the masses of the voiceless so to speak, in order to create a more balanced job market. I’d prefer a system that properly serves science and the scientific community, including those without power. Do count me in for such a movement. But in the meantime, the reality that we face is pretty damn dire, so let’s be realistic, learn a few tips to survive, and do some self-help too.

4. Prepare yourself for failure.

Expect that your application, the one you have spent many months FTE on writing and put your living-breathing soul into, will be rejected.

Develop an armour of self-belief.

Seek out advice on how to cope with rejection. There are many articles on the subject, do a search online too.

Have close friends to cry on their shoulders. You’ll cry a lot. Crying helps, embrace it. (Especially if you’re a guy!) It’s not a sign of weakness – no, it’s a great way to get better and collect your inner strength.

5. Be aware of impostor syndrome, and figure out what you can bring to the table.

Don’t think you are worthless just because you see people around you who seem to be more clever or more productive.

First of all, they may perceive you the same way... impostor syndrome is real, my friend.

Second, science does need people like you, too. You do have special skills that the community can (honestly, should) make good use of.

Some people may be good in grasping theoretical details more quickly, but may not be as good in explaining them to students as those who themselves needed more time to understand them in the first place.

Or, some people might just have had luck discovering something worth a Nature paper (they must have put the effort in it, I’m not saying they didn’t!) while you may find the same luck one day in the future, just not as early as they did.

Or, some people may be very good at working alone or with a supervisor, but not able to work in a team – and especially not able to manage a team, becoming a leader, a good PI... which you might have the talent to be. Some projects are only possible in groups, after all – so we do need good managers.

Indeed, some people may be great in deriving stuff or carrying out complex tasks, but do they possess the broader view, a scientific “vision” that is needed for a successful career nowadays?

I could list yet a dozen things that you may or may not have. Writing up things quickly and clearly, being able to think in systems, being good in statistical methods and big data, giving great presentations, producing brilliantly under time pressure, organizing the most efficient meetings, having a special talent for visualizing data, being able to “translate” between the jargon of different research fields etc. etc. etc.

It really comes down to finding what strengths and weaknesses you have, and building on the strengths while gradually eliminating (or at least carefully avoiding) the weaknesses.

6. Network.

Do network a lot. You never know which new person brings you the next big opportunity. Or, if you don’t like thinking of networking like this (seemingly “using” people for your own gains), think about it in terms of what you can give to people. Cause you will give things to people, be it your expertise and fresh ideas, or “just” your joyful and motivating personality. So, network!

7. Go to workshops on fellowships. And then, try again.

Some universities offer such workshops for free. I went to several of them. I was told there repeatedly that after you have done all the things listed here, it comes down to luck. Because many people have done these things too. There are more eligible candidates than fellowships.

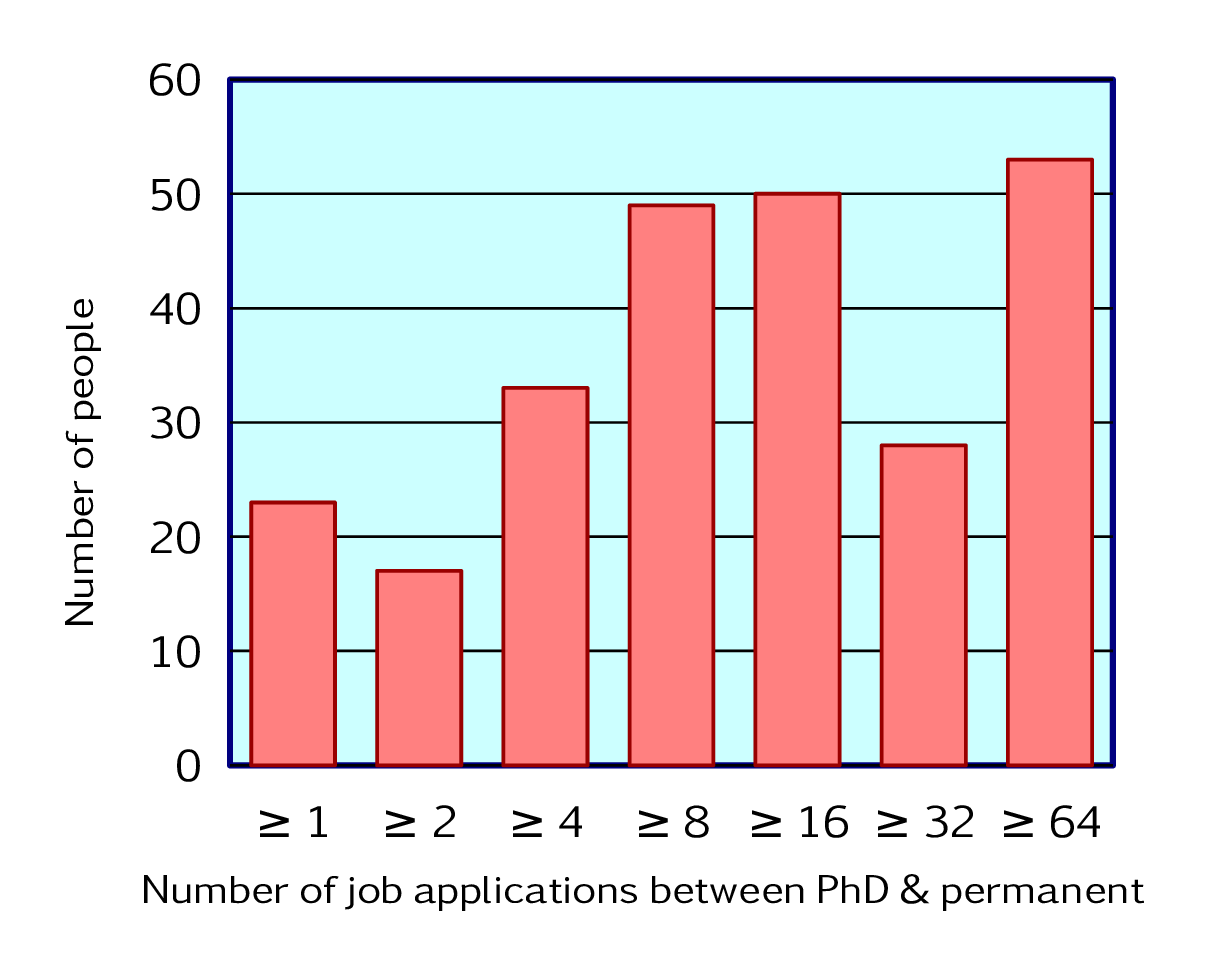

In fact, another small study I have conducted [2] shows that the number of job applications a tenured person has written between her PhD and getting the permanent position can easily be as high as 60 (see figure).

Which means that the fact that someone gets rejected several dozen times, does not necessarily imply that she is a bad scientist.

It only implies that the chances of getting a job in today’s academia are extremely low.

So, the more times you apply, the higher your chances become to get a job – and that applies for fellowships too. Remember that.

8. Learn from the process, even if failed.

When people express interest to work with you but expect you to “find your own funding”, don’t take this as a discouragement. It means they are willing to help with the preparation of the application. Which is great! You can harvest their initial brainstorm about the overall approach. They may share their earlier (successful or unsuccessful) proposals with you. They can read and discuss your drafts.

These are all crucial steps.

The chances to get that particular fellowship may still be low, but what you get out of the process is the mentorship. You will be sharpening your ideas and learning to formulate them better. You will be able to sell your ideas (see my point #3) so that someone outside of your field can get excited about them, and vote in your favour.

Big universities in the West typically have excellent grant writing support offices. If you manage to find a person who is willing to host you at one of these big universities (cf. my point #10 though) and get you in touch with the grant support office, you’ll get all the help you need. Rely on their help, cf. my point #1. They will of course tell you their honest opinion about your research plan, which may hurt, but see again my point #3.

Even if you don’t get the job at the end, you have the chance to learn from the process.

9. Try to find a regular post-doc job, in the meantime.

Even if it means you have to change your subject. Even if it seems you have to make almost a second PhD in a whole new field of research. Don’t be afraid of applying for jobs that don’t perfectly fit your profile! They may still want you. And you may find happiness in the change of subject because it can provide you with new experience, broader knowledge and perspectives.

That said, you may eventually want to find a common motive between your old and new research interests – and use this motive to sell your ideas in your fellowship proposal!

And if you do find a regular post-doc job, make sure your supervisor/boss is aware that you are applying for fellowships. Tell them this right before accepting the offer. Upon getting an offer, you have the opportunity to negotiate the conditions. Make sure your first condition is that you are going to spend, say, 2 month FTE of your time on application writing (cf. my point #2). They must understand this. Don’t be afraid to negotiate; after all, if they offer you a job, it means they want you. So, be brave and stand up for yourself.

10. Look outside of your (Western) bubble.

For Westerners: Don’t be afraid of accepting a job in a developing country. It may seem weird at first, but it is an option, and there are many nice people in those countries doing great research. (And under much less pressure to compete, in many cases at least – which may be good for your mental health!)

Plus, you may learn some important cultural lessons and become a better human being. All while staying in science, strengthening your publication list, and having a chance to apply for fellowships as many times as you need until you succeed. Who knows, moving to an exotic country may be the best decision you ever make, leading to the biggest adventure of your life!

For non-Westerners, like myself: I’m not going to lie to you, dear. To get into a Western country, it may take you ten times the effort than the other way around. I’m not saying it’s fair but it’s true (see my point #3 too, though it'd be worth a whole other article to discuss the particular difficulties of getting a job in the West as a non-Westerner). Prepare for an uphill battle as a lone fighter. Because you can climb that hill. I know you can. Prepare that it may take all you have, but it is possible.

And once you’re there, don’t forget where you’ve come from. Try to make the track climbable for those who may want to step in your footsteps!

11. Take all of it with a grain of salt.

All advice is given from a personal perspective. Yes, that includes these ones as well! They are all informed by personal experiences that don’t necessarily generalize well. Everyone’s advice is based on how they succeeded, and how they might have seen their close colleagues succeed or fail.

There may be some typical pathways to a permanent job in academia, and a fellowship certainly helps. But we all have seen many people forging their own paths in their own special ways. You are unique. Find what makes you unique, and use this special talent wisely.

If it includes going for a fellowship, that’s cool. But if not, that’s cool too.

There is no “right way” to succeed in academia: there are almost as many ways as people.

***

So, as a conclusion, don’t give up. If someone tells you that you’d be wasting your time on applying, or that a fellowship is just not for you, screw them. It’s probably their own frustration with the job market talking. But their own experiences/possibilities are surely different from what yours are.

Maybe something that didn’t work for them, will work for you.

The job market is competitive, and there is a lot of luck involved. But if there is a job/group/department/fellowship you are really excited about, it’s almost always worth the effort of applying. Because not applying is the only way to be sure you won’t get it.

And you will get it. Just don’t give up, okay?

-----------------

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Such great advice for PhDs and postdocs! It's always really helpful to hear from someone who successfully landed a fellowship.

Thanks, Eva! :) <3