Why was a hedgehog taken to Antarctica?

It sounds like a riddle, but it is just one example of the hundreds of alien species that have been intentionally or accidentally introduced to the icy continent and the remote, mostly uninhabited islands in the surrounding Southern Ocean. This and other curiosities, along with species now of major conservation concern, are now made openly available using modern standards as we outline in the paper.

There are many terms to describe alien species (e.g., introduced, invasive, non-native, exotic), but essentially, they are species in places outside their native range due to the influence of people. Alien species can be found everywhere, and the Antarctic region is, sadly, no exception.

The last sheep on Marion Island, 1978. Domestic stock were introduced to many of the Southern Ocean Islands by sealers, whalers, early scientists and settlers (Photo credit: V. Smith, Antarctic Legacy of South Africa archive)

Stowaways, survivors, and those left behind

When early explorers, sealers, whalers, scientists, and settlers set sail for the Southern Ocean Islands, they went prepared. They intentionally released livestock for food, planted vegetable gardens and windbreaks, brought pets and ornamental plants, and explored new farming practices (e.g., livestock, forestry, aquaculture).

To raise sheep, new grasses were introduced. To control the rats and mice that likely survived earlier shipwrecks, cats were released. Different plants were trialled in scientific and forestry experiments. And with cargo and food supplies, many small invertebrates and seeds stowed away.

Reindeer exclusion plot on South Georgia, 2014, showing the recovery of indigenous Acaena magellanica vegetation in response to the removal of grazing pressure, as well as alien dandelions, Taraxacum officinale (Photo credit: S. L. Chown)

Some of these invasions have had devastating consequences for the indigenous species and ecosystems on the islands. Notable examples include widespread cat predation on nesting seabirds, like burrowing petrels, and the transformation of sub-Antarctic vegetation by introduced herbivores, including rabbits and reindeer.

On the Antarctic continent itself, species introductions have spanned teams of sled dogs on the ‘heroic’ expeditions, to more modest infestations of research station sewerage systems by cosmopolitan gnats.

Overall, there have been fewer successful biological invasions on the continent than the Southern Ocean Islands, mostly due to the continent’s harsh environmental conditions. As the climate continues to warm, however, and human activity increases across the region, more alien species will find new, suitable ice-free habitat in Antarctica, unless biosecurity is enhanced.

Cat on Marion Island, 1970’s. Cats were estimated to kill up to ~450,000 burrowing petrels each year on the island until their eradication in 1991 (Photo credit: V. Smith, Antarctic Legacy of South Africa archive)

Changing environmental attitudes over time

Over the last century, attitudes have slowly shifted on the ethics of trying to transform pristine ecosystems into farmland or intentionally releasing non-native species onto islands. We also seem to be altogether less concerned with providing for castaways.

These changing attitudes have been reflected in international agreements on biodiversity, and through local advances in biosecurity and management practices.

The United Nation’s Convention on Biological Diversity recognises the need to “prevent the introduction of, control or eradicate those alien species which threaten ecosystems, habitats or species” (Article 8(h)).

In the co-governed Antarctic Treaty area (south of 60°S), these changing attitudes were reflected in 1991 when nations that are party to the Antarctic Treaty adopted the Protocol on Environmental Protection to the Antarctic Treaty. The Protocol outlines their commitment to the comprehensive protection of Antarctic ecosystems. Among other things, it prohibits the introduction of domestic stock, sled dogs and non-sterile soil, and the introduction of other living organisms is subject to strict permit conditions.

The Southern Ocean Islands (north of 60°S) are managed separately by the various countries that have annexed them. Here, there has also been an increasing focus on biosecurity, alien species control, and eradication programs.

To support these international commitments, there has been increasing global effort to compile and exchange data on biological invasions. Inventories of alien species records, such as the Global Register of Introduced and Invasive Species (GRIIS) and CABI Invasive Species Compendium, were developed to provide open, interoperable, and reusable data.

These inventories provide evidence to support policy and conservation decisions, such as:

- Where should surveillance and management efforts be prioritised?

- Which taxonomic groups might be under-surveyed (e.g., fungi)?

- Is the number of alien species with a harmful or invasive impact changing over time?

- How successful have biosecurity or eradication programs been?

- Which alien species have established in neighbouring areas or pathways of introduction that might pose a future risk?

Introduced and invasive alien species of Antarctica and the Southern Ocean Islands

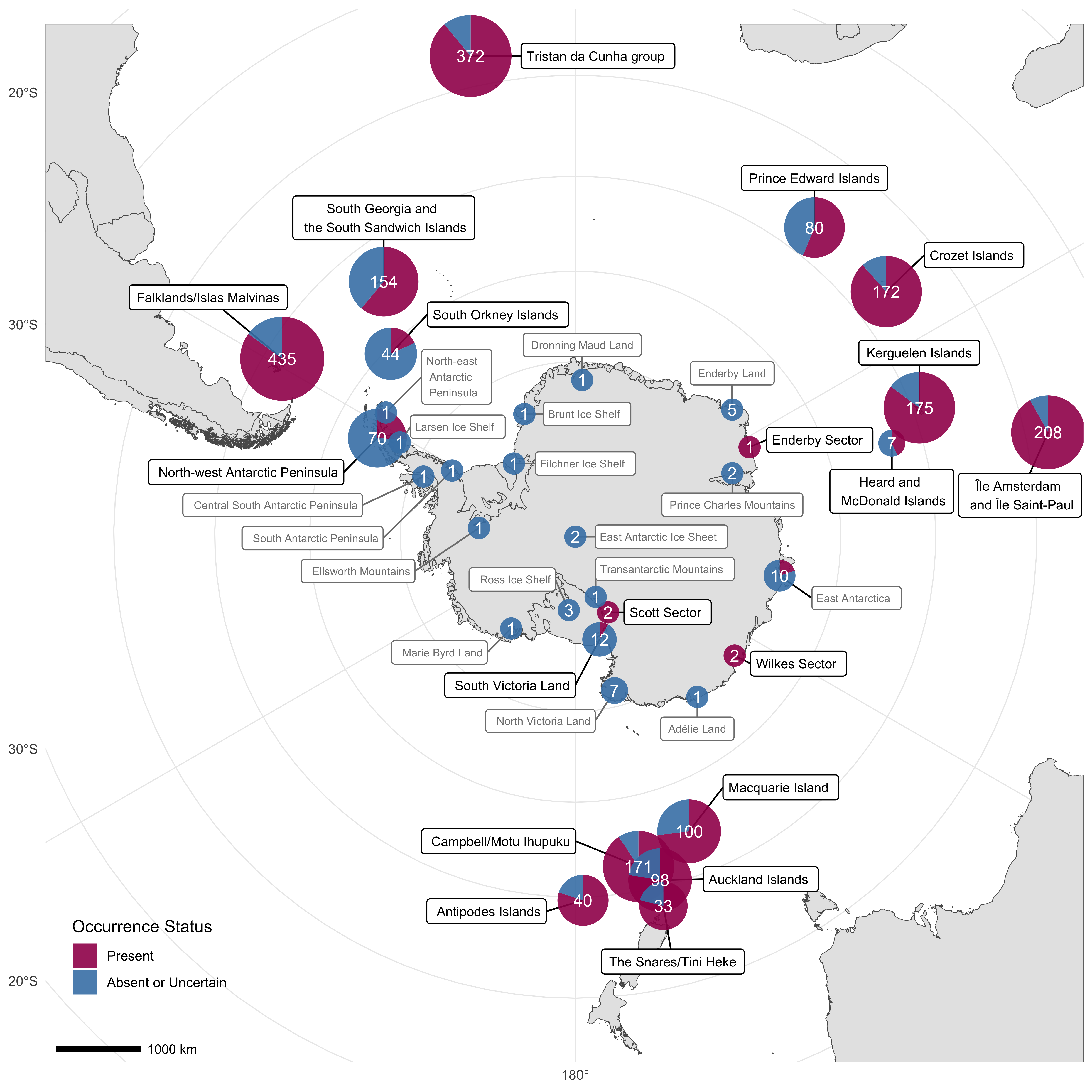

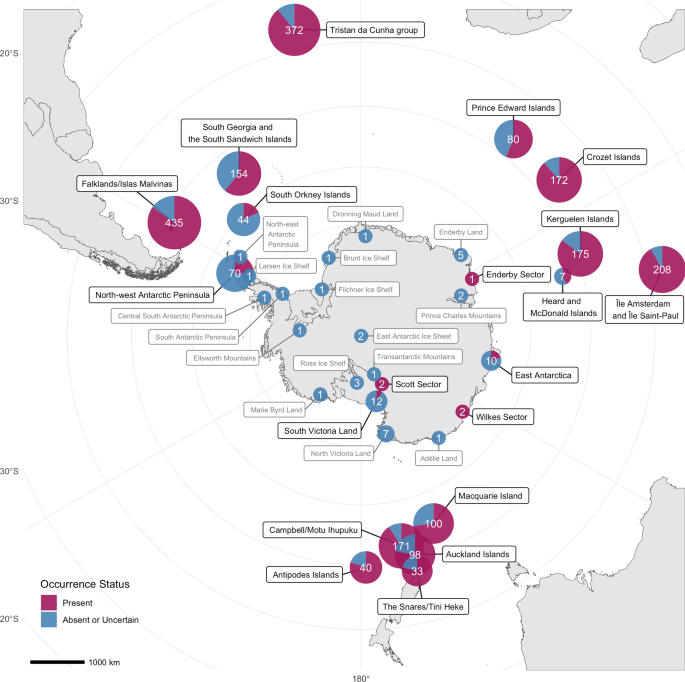

To provide such evidence for Antarctica, we developed what is, to our knowledge, the most complete and up-to-date inventory of introduced terrestrial and freshwater species for the broader Antarctic region. It builds on many published data sources to provide information on the identity, localities, establishment, eradication status, dates of introduction, habitat, and evidence of impact of alien species. We took a broad historical perspective, including alien species that were introduced to Antarctic sites but have since died out, been successfully eradicated or removed, plus ongoing invasions.

We used recent advances in bioinformatics standards to ensure the data can be used with existing registers of introduced species. We also include data on the introduction dates of records and their eradication status to help researchers and managers track the temporal dynamics of invasions and eradications. Indeed, those temporal dynamics are the subject of our next paper.

The dataset is a starting point. Because biological invasions are dynamic processes, a species list is never final. It needs to be updated as new introductions occur, the impact of invasive species changes, new research is undertaken (e.g., taxonomic revisions), or when eradication efforts prove successful.

These data will contribute to our understanding of the extent, trends, and impact of biological invasions in the broader Antarctic region. There is a lot we still need to learn. For example, I don’t yet know what they wanted the hedgehogs for.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Data

A peer-reviewed, open-access journal for descriptions of datasets, and research that advances the sharing and reuse of scientific data.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Data for crop management

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 17, 2026

Data to support drug discovery

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 22, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in