The Untold Story Behind Studying Edible Crops Grown on Dumpsites

Published in Healthcare & Nursing, Public Health, and Agricultural & Food Science

When we think about food, we imagine nourishment, health, and the comfort of traceability (i.e., knowing where our meals come from). Yet in many parts of the world, including many developing and even some developed nations, the question of where food is grown is far more complex.

Long before this research began, I often wondered how families living near waste dumps managed to survive, especially when the dumpsite itself was close to their water sources or had become their farmland. That curiosity, mixed with deep concern, sparked a journey that eventually became this study.

This project takes place at the Mbale municipal dumpsite, a sprawling four-hectare space filled with industrial, household, hospital, market, abattoir, and electronic waste. But it is also filled with life: green vegetables, fruiting crops, grains, and herbs. Farmers cultivate this land not because it is ideal, but because it is available. Their harvests feed their families, and the surplus is also sold at nearby markets. The big question was simple, yet urgent: What exactly are people eating when their food grows on a dumpsite?

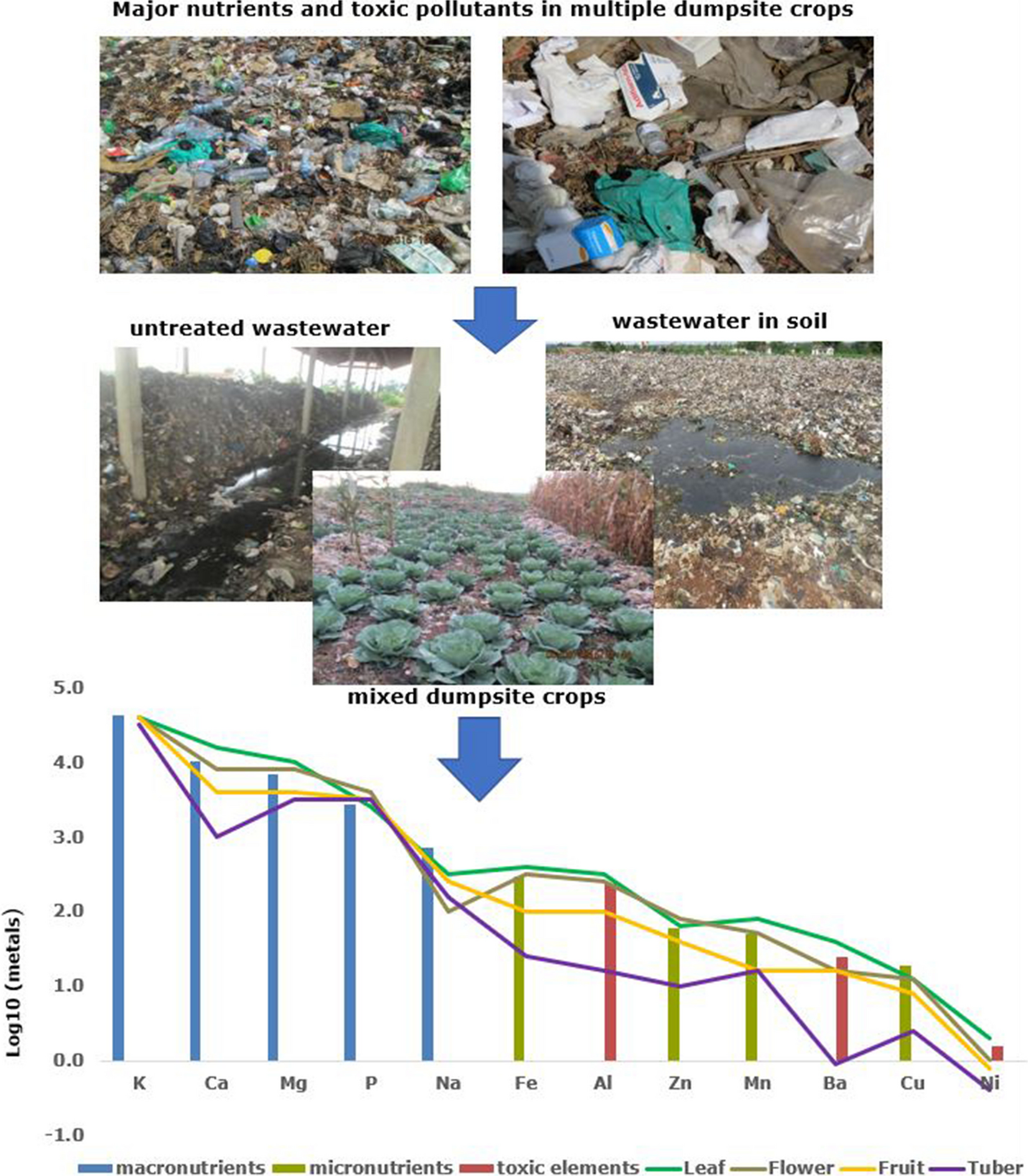

Fig. 1: Chemical flow from mixed waste source (a) to leachate (b) and to food drops (c) Fig. 1: Chemical flow from mixed waste source (a) to leachate (b) and to food drops (c)

|

Where the Idea Began

My interest in this topic began years earlier, during my work on groundwater chemistry, environmental pollution, and subsequently on food chain contamination. Time and again, the same issue resurfaced: not only were dumpsite chemicals cited in water sources, but also in agricultural soils and edible crops, with communities in low-income areas growing food crops in contaminated environments, without any monitoring.

In some developed countries, and many developing nations, including Uganda, municipal dumpsites develop informally, without engineered liners, leachate controls, or fencing. Over time, they transform into complex social spaces where waste pickers, farmers, livestock keepers, and children interact daily. Illegal burning, scavenging, and unregulated waste disposal had been occurring at the Mbale site long before our research started. As the city grew, so did the waste, while regulation did not.

Whenever I visited Mbale, I saw some women, youth, and children scavenging for recyclables, while others were mining metals and tending lush gardens on the mounds of decomposing waste. The produce looked healthy: vibrant greens, plump tomatoes, and colourful amaranths, among others. But looks can be deceiving. I knew that waste-rich soils can contain high organic matter, as well as nutrients and toxic metals. The farmers and maybe some municipal workers did not.

One day, I remember meeting an elderly woman tying bundles of leafy dodo (amaranth), who told me, “This is the land God gave us. If we don’t grow here, where else can we grow?” Her words stayed with me. They motivated the study more than any academic question ever could.

Fig. 2: Various activities conducted at the Mbale waste dumping site

The Reality on the Ground

The Mbale dumpsite is not a uniform space. It is shaped like a shallow basin with three distinctive zones: a central mound, a sloping middle, and a riverbank area bordering the Namatala River. Each zone receives different types of waste and experiences varying levels of burning, flooding, and soil disturbance. Waste is not sorted, meaning plastics, batteries, medical sharps, food scraps, metals, ashes, and e-waste all break down together.

Field observations showed how deeply the dumpsite was integrated into local livelihoods: (a) people grew vegetables during rainy seasons, (b) goats and cattle grazed freely, (c) waste pickers collected metals, plastics, and electronics, (d) children helped their parents after school, and (e) nearby households used the dumpsite as a shortcut to the river. This constant movement of people and animals stirred contaminated dust and redistributed polluted soil, creating a patchwork of exposure across the site.

Fieldwork: Between Curiosity and Caution

Our fieldwork took place between November 2016 to January 2017. Some days were unbearably hot, while on others the stench was overwhelmingly strong even through masks. Yet the crops thrived in the waste-rich soils, growing faster and larger than those cultivated in ordinary soils. Across all zones, we collected 192 samples from 31 crop types, including leaves, fruits, tubers, seeds, and grasses. Each sample was carefully labelled, dried, and prepared before being shipped for laboratory analysis.

Fig. 3: Sampling in progress

On several visits, school-aged children were helping their families to sort recyclables, sieve compost, mine metals, or pick vegetables. Some had come before school to scavenge or mine to earn money. Others lived so close to the site that smoke from burning waste drifted into their houses. Many farmers told us that the organic-rich waste acted like “free fertiliser.” They appreciated the fast crop growth, without realising the nutrients were mixed with industrial chemicals and metals. Several ate some of the crops themselves and sold the rest to neighbouring communities, unknowingly extending contamination into the wider food system.

Fig. 4: Scavenging, livestock farming, and other agricultural activities around the dumpsite

What Surprised Us Most

We expected contamination. However, what we found was a mixture of high nutritional value and high toxicity. Crops were extremely nutrient-rich with large amounts of essential elements such as potassium, magnesium, calcium, phosphorus, zinc, and iron. In fact, some leafy vegetables contained nutrient levels even higher than those in supermarket produce.

But the same crops were contaminated with toxic elements, including aluminium, lead, chromium, nickel, barium, mercury (trace), and cadmium (trace). Leafy vegetables accumulated 50–75% more metals than fruits or tubers, making them the most dangerous.

Each zone had its own contaminant signature: Dump Centre → highest in chromium, aluminium, and iron; Slope → highest in zinc and copper (likely due to burning of waste); and Riverbank → highest in barium (linked to upstream industrial runoff). This gradient helped map how waste breaks down and spreads over time.

The dumpsite soils had extremely high organic matter, acting like a sponge that held both nutrients and toxins. Metals were found not only in topsoil but also in deeper layers, showing contamination had been building for years. During rainy seasons, polluted leachate moved downward and outward, flowing toward the Namatala River and seeping into groundwater.

This created a chain of exposure: waste → soil → crops → water → humans and livestock.

Fig. 5: Flooding affecting the Mbale dumpsite, R. Namatala, and surrounding agricultural fields

Interacting with the Community

Discussing our initial results with the farmers and site workers was eye-opening. Many were shocked, others suspected risks but felt powerless, while some urged us to share findings with local authorities to inspire better waste management. A recurring theme emerged through the conversations: Some people do not farm on dumpsites out of ignorance, but they do so out of necessity. This reinforced the importance of sharing scientific results in understandable and accessible formats, such as local languages, visual materials, community meetings, and school outreach.

Why This Research Matters

This study is more than an academic exercise. It highlights a global issue affecting millions of people worldwide: urban agriculture in contaminated environments. This can happen when people grow food directly on dumpsites, or when they buy food from the global market that was grown using contaminated compost. The work shows that:

- Dumpsite farming can strengthen food security, but it also exposes consumers to dangerous toxins posing health risks.

- Leafy vegetables, which are our daily staples in local diets, absorb the highest metal concentrations

- Some crops (groundnuts, cereals, soybeans) uptake fewer toxins and may be safer alternatives.

- Weak waste management systems and a lack of food-source traceability increase exposure risks.

- Contamination can travel beyond local areas through markets and global compost supply chains.

- Children and pregnant women are especially vulnerable, as toxic metals interfere with iron, zinc, and calcium absorption, nutrients critical for growth and development.

- Until waste is sorted, treated, and safely contained, contaminated food production will continue.

Above all, the study reinforces the need for community-centred solutions, including education, soil remediation strategies, safe crop selection, and long-term monitoring.

Reflections and Lessons Learned

Researching dumpsite farming showed me the resilience and vulnerability of communities living at the edges of urban systems. It is one thing to read about contamination; it is another to hold a leaf that is both nourishing and toxic at the same time. The journey reminded me that:

- Science must serve the communities it studies.

- Evidence is only meaningful when communicated clearly & shared in accessible ways.

- Sustainable solutions must respect lived realities.

This research is only the beginning. It calls for stronger waste management infrastructure and policies, safer food guidance, and long-term environmental monitoring.

Moving Forward

I hope that policymakers, researchers, and community leaders will rethink the connection between waste, environment, and food safety. Most importantly, I hope this work gives a voice to the families who rely on these contaminated lands not by choice, but by circumstance. Their health and their future depend on the decisions we make next. Together we can save lives.

Follow the Topic

-

Environmental Monitoring and Assessment

This is a journal that explores the design and implementation of monitoring systems and pollution risk assessment methods.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in