Understanding leaf variability within tree species

Published in Ecology & Evolution

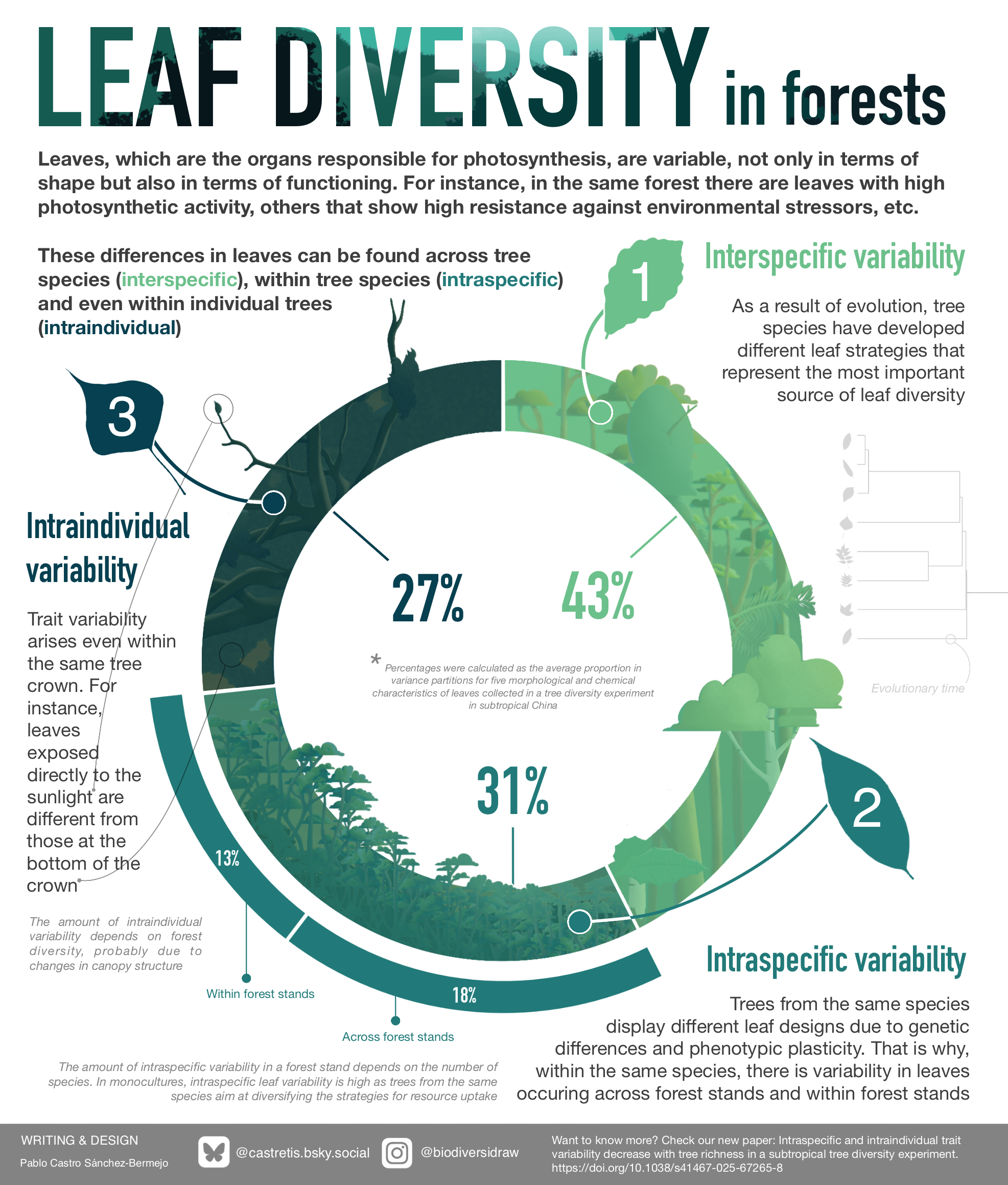

Sources of leaf variability

When walking into a forest, it is easy for any person with a little botanical knowledge to distinguish between different tree species simply by looking at the shape of their leaves. For instance, the English oak has leaves with rounded lobules that are easily recognisable, and we would never confuse them with the palmate-shaped leaves of the field maple. Nevertheless, by focusing on leaf shape, we overlook the fact that there are other characteristics of leaves (hereafter referred to as ‘functional traits’) that are more closely related to the functioning and performance of trees. One of these is specific leaf area, defined as the ratio between leaf area and mass, which describes a gradient from leaves that invest more in area to prioritise photosynthetic activity to thicker leaves with lower photosynthetic activity but higher resistance to stressors. Therefore, specific leaf area, together with other functional traits such as leaf nitrogen or leaf dry matter content, has become one of the main indicators of tree functioning. In the case of these functional traits, it is probably much harder for us to distinguish whether maple leaves have a higher specific leaf area than oak leaves. Indeed, if we were to collect hundreds of leaves per species, we would probably notice already in the field that, within the same species, leaves differ in size and weight. Even though we can clearly distinguish species by leaf shape, the functional traits of leaves can be much more variable. This is why, when considering these functional traits, differences among species are not the only component of leaf diversity and it is important to recognise that leaves can also vary: (1) between individuals of the same species (intraspecific trait variation) as a result of different trait expression associated, for instance, with competitive interactions, and (2) within the same tree (intraindividual trait variation) as a result, in many cases, of different locations within the crown. In a recent study, we aimed to characterise the trends and importance of these two sources of trait variation occurring within tree species along an experimental gradient of forest diversity ranging from monocultures to eight-species mixtures.

Measuring leaf diversity in the field

In a study of this kind, the number of leaves to sample and process increases exponentially as different sources of trait variation are included. In our study, we aimed to include eight tree species, different individuals per species and forest stand, and, eventually, several leaves within the same crown. This resulted in 4,568 leaves. Considering that we wanted to measure five functional traits in each leaf, this amounted to a total of 22,840 measurements. In order to streamline the process and lighten the workload, we decided to use leaf spectroscopy coupled with machine learning as a method of leaf phenotyping. Leaf spectroscopy relies on the fact that morphology and chemical composition affect the optical properties of leaves. While these optical changes may be undetectable by sight, they are, in many cases, detected through patterns of light absorbance at higher wavelengths. Therefore, we acquired the spectral signal of each leaf using a spectroradiometer and calibrated convolutional neural networks (a type of machine learning algorithm) to predict functional traits in the leaves.

Another interesting aspect of our study is that we made use of a long-term forest experiment in which a gradient of species richness was generated in order to better understand the effects of tree diversity. In natural ecosystems, gradients in species diversity are rare unless they result from environmental factors. For instance, it is common for the number of tree species to decrease as we move uphill in a mountain, but this limits our ability to study the effects of diversity independently of climate. In contrast, greenhouse experiments can easily control environmental conditions, but they typically rely on tree seedlings and may oversimplify forest conditions. As a result, tree diversity experiments, such as the BEF-China experiment where we conducted our study, provide a good trade-off to test patterns of trait variation in forests. The BEF-China experiment was planted in 2009, which makes it feel already like a "real forest", but it was designed as an experiment, which allows to control for environmental factors.

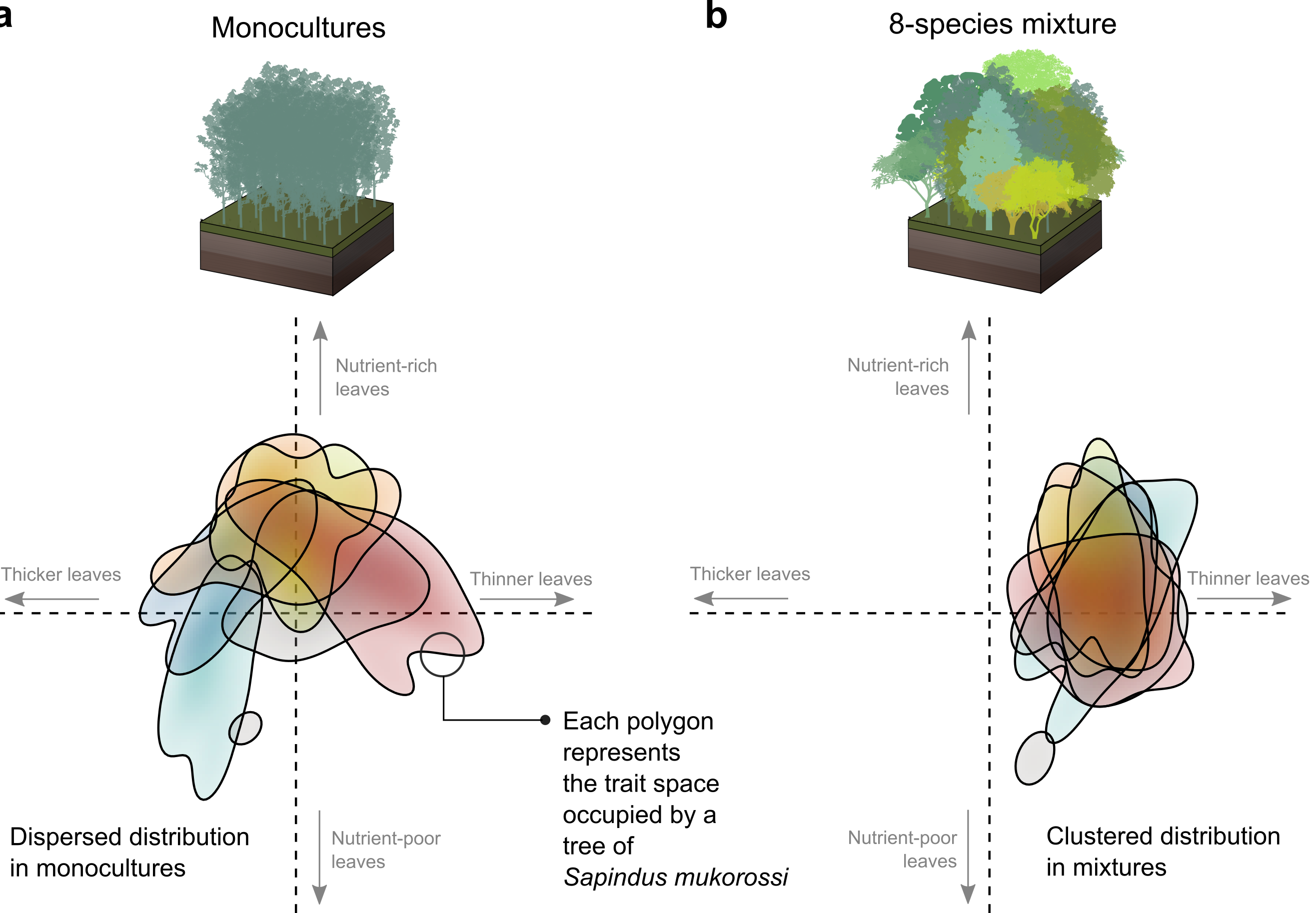

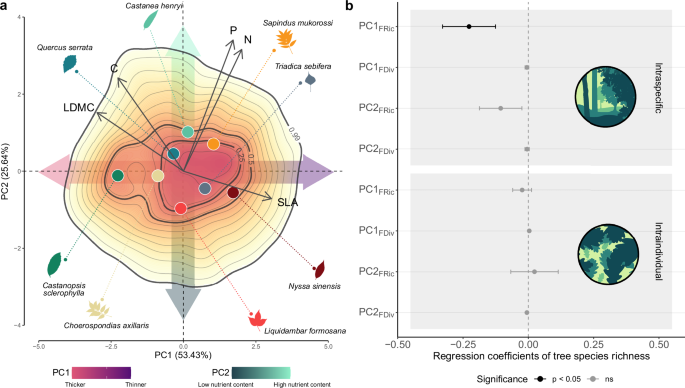

Functional trait shyness

I have always been fascinated by the phenomenon of crown shyness that occurs in some natural monocultures, in which the tips of branches seem to avoid touching each other, resulting in fully stocked crowns that do not overlap and form a canopy with channel-like gaps. In this context, conspecific trees (trees of the same species within the same forest stand) appear to partition space occupation. In our study, we have shown that something similar occurs in the case of functional traits. A species growing in monocultures displays a wide range of leaf designs, and this seems to occur because conspecifics avoid being too similar in their leaf strategies: some trees prefer smaller and thicker leaves, other trees larger and thinner leaves, some trees are richer in nitrogen than others, and so on. Therefore, if we were to illustrate the leaf strategies of trees in a ‘trait space’ (a common procedure in ecology to visualise and estimate leaf diversity using geometric shapes) we would find that conspecifics in monocultures tend to avoid each other, reflecting a kind of ‘functional trait shyness’ syndrome. In contrast, in mixed forest stands, the same species that showed strong differences in functional traits in monocultures display much smaller differences. This is probably because adopting a common strategy among conspecifics in mixtures is beneficial in order to avoid competitive interactions with trees from other species.

Why understanding leaf diversity in a forest matters

As in the case of the oak and the maple, leaf diversity in our study can only be understood by considering intraspecific and intraindividual variation. While it is true that, on average across all functional traits, differences among species represent 43% of leaf diversity in our forest stands, intraspecific and intraindividual leaf variation together account for more than half of the leaf diversity we measured. In addition, we found that leaf diversity within a forest stand is higher when accounting for specific intraspecific and intraindividual trait variation, as these two sources appear to be organised in a way that maximises leaf diversity. The open question now is how this translates into forest functioning. Leaves are the main organs for photosynthesis in plants, making them extremely important for primary productivity, and they are involved in many other ecosystem functions, such as herbivory. Therefore, intraspecific and intraindividual trait variation can have important implications for forest functioning. Thus, I feel that future research should investigate how diversity in leaf form and function within species affects the ability of forests to respond to environmental changes and to ensure the provision of ecosystem functions.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in