Association between weight and outcomes in intensively-treated acute myeloid leukemia

Published in Cancer and General & Internal Medicine

The Why

The World Health Organization defines obesity as a body mass index (BMI) of 30 kg/m2 or greater, and a recent study found 49% of patients with acute myeloid leukemia (AML) meet this criteria.1 Interestingly, while obesity is associated with increased risk of developing some solid and hematologic malignancies, there is ongoing debate on the relationship between obesity and outcomes in patients with AML. 2–5

To date, there have been limited studies investigating differences in outcomes among patients with obesity, including different degrees of obesity. Obesity can be further classified into: class I obesity (BMI 30 to <35 kg/m2), class II obesity (BMI 35 to <40 kg/m2) and class III obesity (BMI ≥40 kg/m2). When considering intensive induction chemotherapy, a patient with AML and a BMI of 45 kg/m2 may have a very different body composition, risk factors and thus outcomes than a patient with a BMI of 30 kg/m2.

Our study aimed to examine the association between classes of obesity and outcomes in patients with AML treated with induction chemotherapy and, in a subset, allogeneic hematopoietic cell transplant (HCT).

The How

We conducted a post-hoc analysis of patients enrolled in SWOG S1203, a large clinical trial which enrolled 738 previously untreated younger patients with AML between 2012 year and 2015 year.6 Patients were randomized to three treatment arms for induction chemotherapy: daunorubicin and cytarabine (“7+3"), idarubicin and high-dose cytarabine (IA; both administered by continuous IV infusion), and IA plus the histone deacetylase inhibitor vorinostat. Patients with severe comorbidities precluding intensive chemotherapy were excluded. Of note, this study was conducted before the 2021 American Society of Clinical Oncology guideline recommending full weight-based chemotherapy dosing in obese patients, and there was a body surface area cap for daunorubicin and idarubicin.7

The What

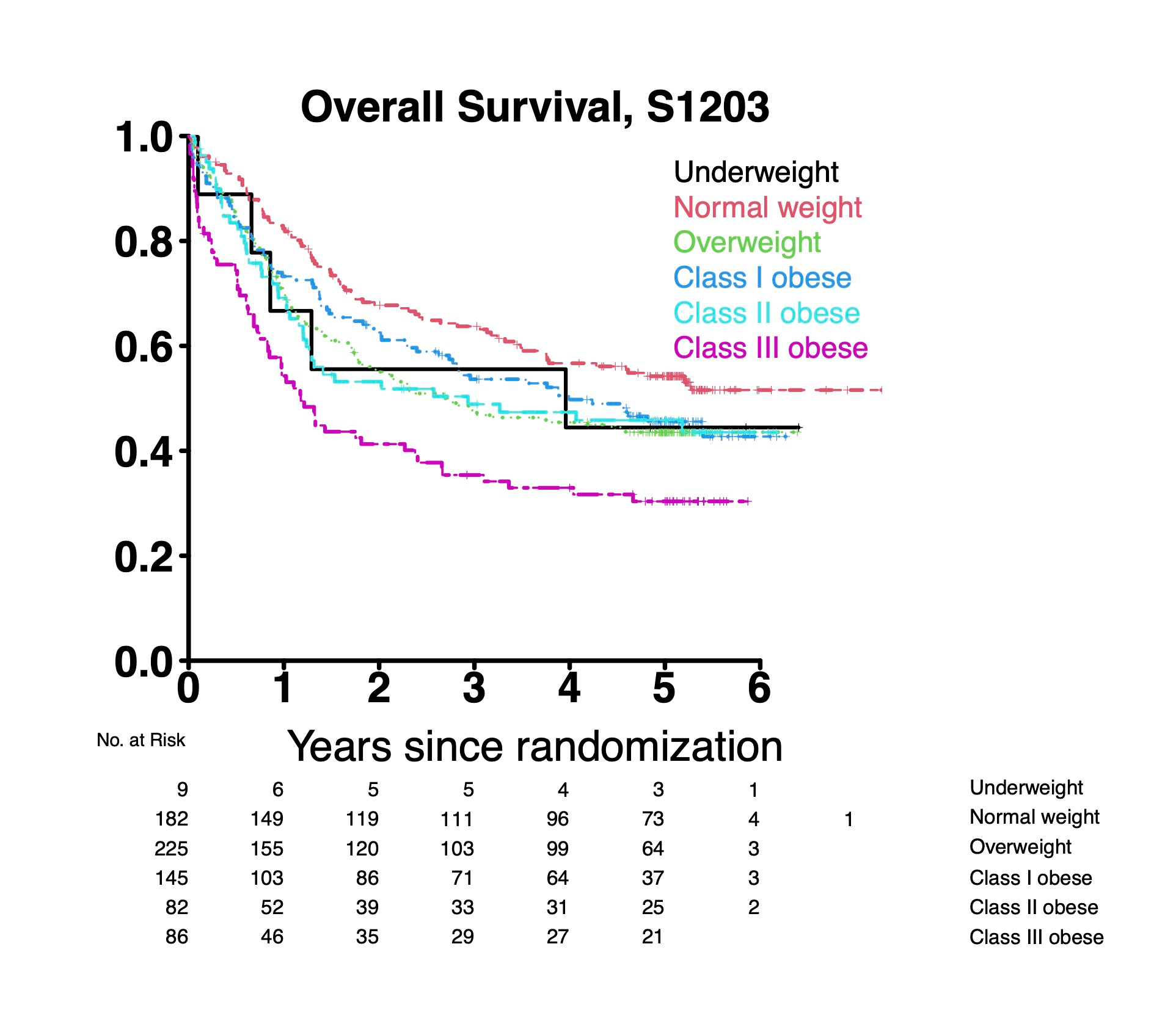

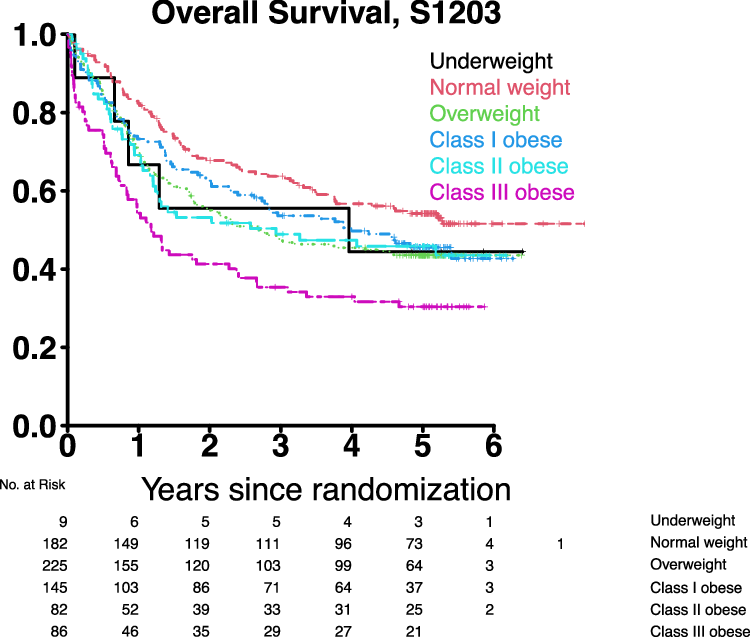

Overall we identified a significantly higher rate of early death (defined as death within 28 days of induction chemotherapy) in patients with class III obesity compared to normal weight (10% vs 2%; p=0.006). In multivariable analysis controlling for age, sex, race, performance status, secondary disease status, cytogenetic risk and transplant status, class III obesity was significantly associated with worse overall survival (OS) compared to normal weight patients [hazard ratio (HR) 2.48, 95% CI 1.62-3.80]. While there was a trend toward worse OS in class I and II obesity, these did not reach statistical significance (see figure below). In the subset of patient who went on to HCT, class III obesity was also significantly associated with worse OS after HCT (HR 2.37, 95% CI 1.24-4.54 versus normal weight), whereas class I and class II obesity were not significantly associated with worse OS. Taken together, these results suggest that younger previously untreated patients with AML and class III obesity are at increased risk of poor outcomes across multiple timepoints in treatment: from early death after chemotherapy to poor long-term outcomes after HCT.

These results raise interesting questions about the pathophysiology of our findings regarding worse OS in patients with class III obesity. Our study was not designed to answer this question, though we hypothesize that differences in muscle mass, comorbidities, or the dosing of intensive chemotherapy could be contributing to worse outcomes in patients with class III obesity.

Take-home messages

- Our study using patients from S1203 suggests that patients with AML and class III obesity are uniquely at risk for worse outcomes throughout their treatment course.

- Future prospective studies are needed to confirm these findings and investigate contributory factors.

- Characterizing patients at risk for worse outcomes may help guide patient counseling and provides a first step toward designing interventions.

References:

1 Castillo JJ, Mulkey F, Geyer S, Kolitz JE, Blum W, Powell BL et al. Relationship between obesity and clinical outcome in adults with acute myeloid leukemia: A pooled analysis from four <scp>CALGB</scp> (alliance) clinical trials. Am J Hematol 2016; 91: 199–204.

2 Li S, Chen L, Jin W, Ma X, Ma Y, Dong F et al. Influence of body mass index on incidence and prognosis of acute myeloid leukemia and acute promyelocytic leukemia: A meta-analysis. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 17998.

3 Bhaskaran K, Douglas I, Forbes H, Dos-Santos-Silva I, Leon DA, Smeeth L. Body-mass index and risk of 22 specific cancers: a population-based cohort study of 5·24 million UK adults. Lancet 2014; 384: 755–765.

4 Tavitian S, Denis A, Vergez F, Berard E, Sarry A, Huynh A et al. Impact of obesity in favorable‐risk <scp>AML</scp> patients receiving intensive chemotherapy. Am J Hematol 2016; 91: 193–198.

5 Brunner AM, Sadrzadeh H, Feng Y, Drapkin BJ, Ballen KK, Attar EC et al. Association between baseline body mass index and overall survival among patients over age 60 with acute myeloid leukemia. Am J Hematol 2013; 88: 642–6.

6 Garcia-Manero G, Podoltsev NA, Othus M, Pagel JM, Radich JP, Fang M et al. A randomized phase III study of standard versus high-dose cytarabine with or without vorinostat for AML. Leukemia 2024; 38: 58–66.

7 Griggs JJ, Bohlke K, Balaban EP, Dignam JJ, Hall ET, Harvey RD et al. Appropriate Systemic Therapy Dosing for Obese Adult Patients With Cancer: ASCO Guideline Update. J Clin Oncol 2021; 39: 2037–2048.

Follow the Topic

-

Leukemia

This journal publishes high quality, peer reviewed research that covers all aspects of the research and treatment of leukemia and allied diseases. Topics of interest include oncogenes, growth factors, stem cells, leukemia genomics, cell cycle, signal transduction and molecular targets for therapy.

Your space to connect: The Primary immunodeficiency disorders Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Clinical Medicine, Immunology, and Diseases!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in