Balloon seismology enables subsurface inversion without ground stations

Published in Astronomy and Earth & Environment

Why use balloons to do seismology?

Like a drum emitting sounds, ground shaking can couple to the atmosphere as acoustic waves. These acoustic waves mainly consist of infrasound— a type of low-frequency sound (<20 Hz) inaudible to the human ear.

In recent years, this process has enabled the detection of earthquakes and tsunamis by above-ground sensors: by observing perturbations in Global Navigation Satellite System (GNSS) signals, variations in light emission at the top of the atmosphere (known as airglow), or through acoustic sensors carried by balloons.

Artist impression of a Vega Balloon

flying on Venus (Joris Wegner)

With surface conditions reaching 500 °C and pressures around 90 bar, Venus is extremely hostile to electronic instruments placed on the ground. Yet, balloon missions have already been demonstrated: in 1985, the Soviet Vega 1 and Vega 2 missions successfully deployed two balloons that floated at about 54 km altitude. And because Venus' atmosphere is so dense, the coupling between seismic waves and acoustic signals could be up to 60 times stronger than on Earth.

But what exactly do infrasound signals from balloons look like—and what kinds of planet exploration questions can they help us answer?

The Strateole2 campaign and the 2021, Mw 7.3 Flores earthquake

Right now, there are no balloons on Venus, so we will have to wait until there is a first recording of a venusquake. In the meantime, recent Earth-based experiments are already delivering exciting results. In 2021, the French–US Strateole-2 project launched 17 balloons from the Seychelles, in the Indian Ocean. These balloons floated in the tropopause (~18 km altitude) and lower stratosphere (~20 km altitude) for up to three months. While their main purpose was to study climate processes, they also carried a Thermodynamics SENsor (TSEN) equipped with a 1 Hz sampling rate pressure sensor—perfect for detecting infrasound.

On December 14, 2021, four of the balloons happened to be located between 680 and 2,800 km from a magnitude 7.3 earthquake in the Flores Sea. Remarkably, they captured infrasound signals that closely resembled those recorded by nearby ground-based seismometers.

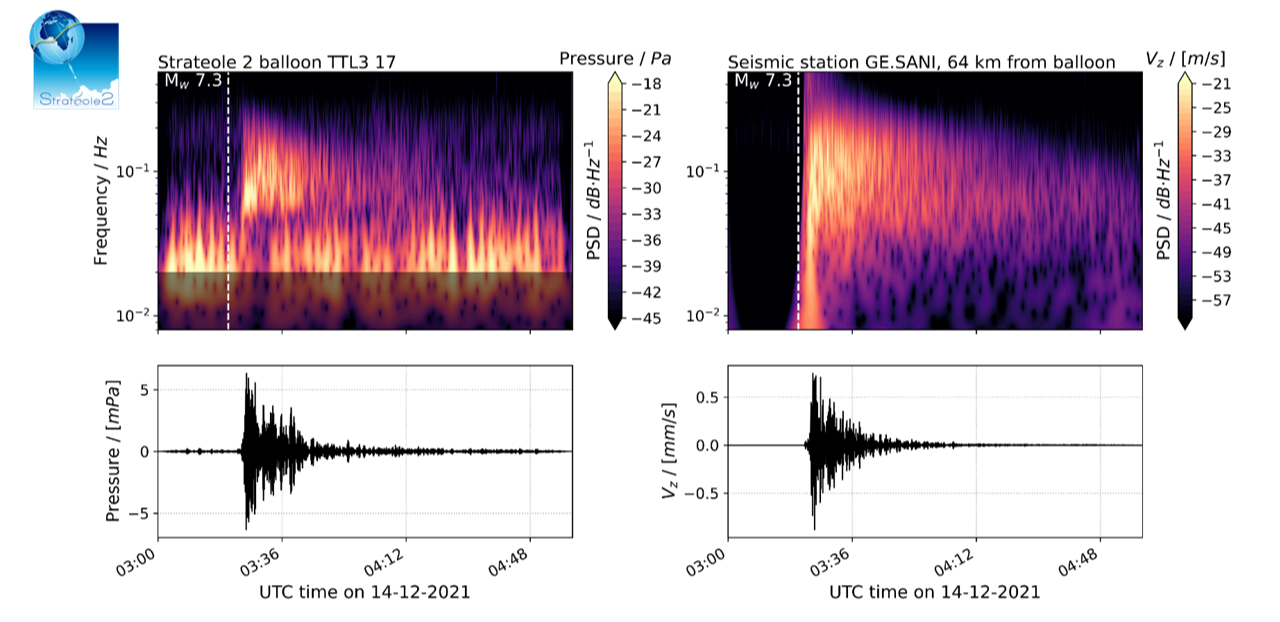

Spectrogram and time series of the pressure signal recorded by Strateole-2 balloon TTL3-17 (left), compared to the seismic velocity recorded at a seismometer on the ground (station GE.SANI, right), only 64 km away from the balloon. The white dashed line marks the start of the Mw 7.3 Flores earthquake.

These data—made publicly available by the Strateole-2 projecty—offer a unique opportunity to explore what balloon-borne seismology can do. Measuring the arrival times of seismic phases at multiple sensors allows, in theory, the localization of an earthquake’s hypocenter. In addition, specific wave types, such as surface waves, contain precious information about subsurface structure and seismic velocities.

Our Findings

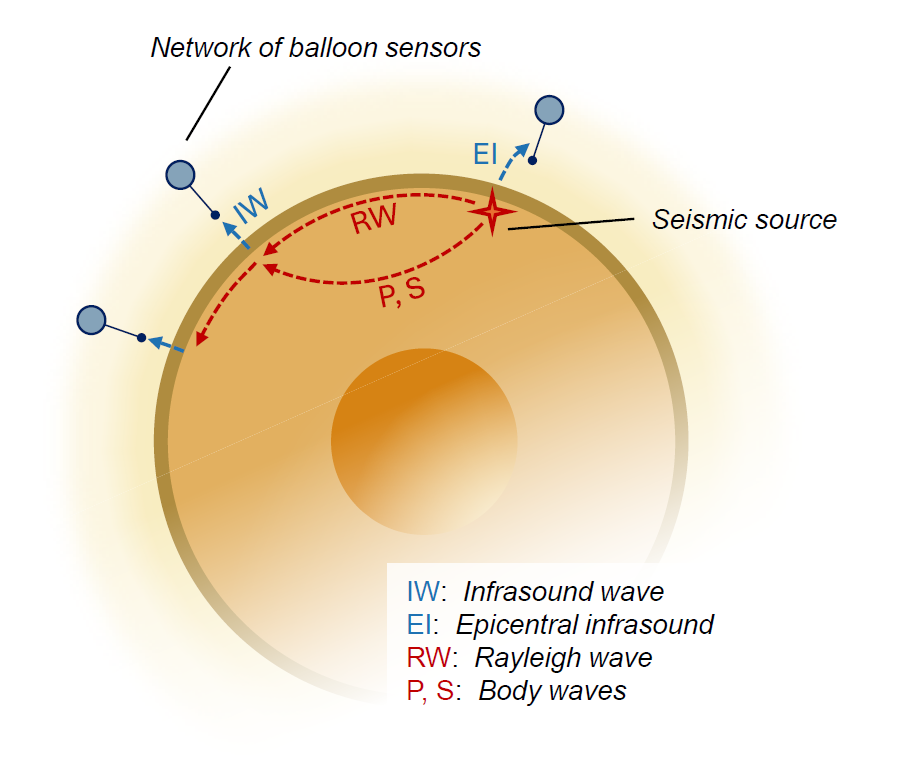

To locate the earthquake and infer subsurface properties from the balloon data, our first challenge was to identify the seismic phases. This wasn’t straightforward, for two main reasons. First, balloons record only pressure perturbations—a single-component signal—whereas most conventional phase identification techniques rely on the three-dimensional motion recorded by seismometers (vertical, transverse, and horizontal). We had to develop our own protocol based on signal envelopes and Frequency-Time Analysis to identify arrivals in the pressure records.

Schematic representation of the different types of

seismic phases, converted to infrasound,

that a network of balloons can record.

Second, the superpressure balloons used in Strateole-2 are affected by buoyancy oscillations in the stratosphere—they bob up and down in response to vertical wind fluctuations. Because the atmosphere is stratified, these vertical motions lead to changes in background pressure, which tend to mask low-frequency signals. We managed to correct for this effect, to some extent, using data on the balloons’ vertical position.

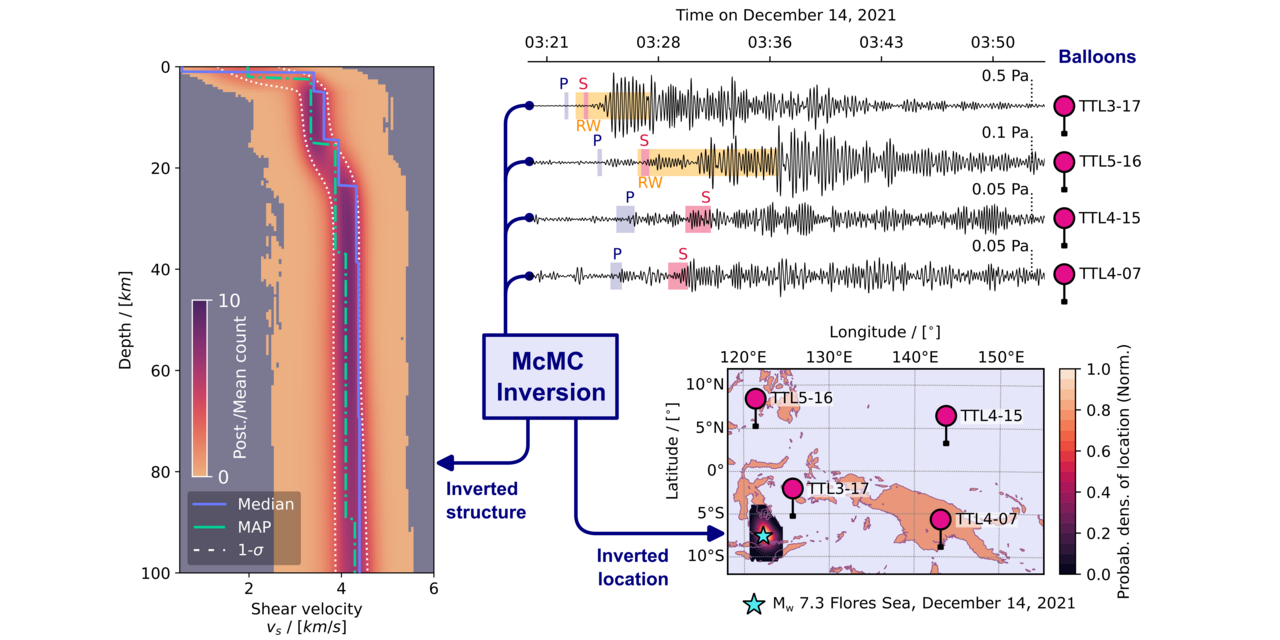

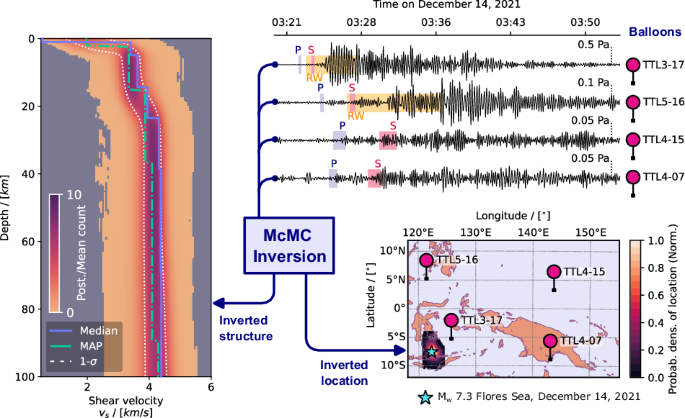

Despite these challenges, the balloon recordings from Strateole-2 provided enough information to constrain both the earthquake source location and the shear-wave velocity structure of the Flores Sea region, down to about 400 km depth. We used a Bayesian inversion approach with Markov Chain Monte Carlo sampling to estimate uncertainty in the inferred source and subsurface parameters. Our results were validated against traditional seismic data from 11 ground stations and tested for sensitivity to different seismic phases.

Ultimately, this study demonstrates that a network of balloon-borne acoustic sensors can provide the information needed to understand the subsurface structure of another planet. It’s a compelling step forward—and suggests that balloon-based seismology provide a powerful alternative to ground seismometers, especially on Venus.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in