Behind the paper: The givers and takers of global invasion costs

Published in Sustainability

Note: a previous version of this post had a shipping-related cover image that was changed for clarity. It may continue to display on old link previews. Previous image credit: Global shipping route frequency in 2007 based on data from Lloyd’s Register Fairplay (www.sea-web.co), from Kaluza, P., Kölzsch, A., Gastner, M. T., & Blasius, B. (2010). The complex network of global cargo ship movements. Journal of the Royal Society Interface, 7(48), 1093-1103.

While globalization has its benefits to economic prosperity, the intercontinental movement of people and goods poses a threat to global sustainability by accelerating the flows and costs of biological invasions (Figure 1). Biological invasions occur when species are introduced by humans outside of their native range, with invasive alien species having enormous environmental and economic impacts. Being tightly linked to trade and transport patterns, these costs may not be borne equally around the globe and thus can challenge conservation and human wellbeing, especially in countries with smaller economies. Invasive alien species can be introduced intentionally or intentionally by humans, such as through the exotic trade in pets or as stowaways on ships. Their numbers are constantly increasing, driving biodiversity loss and costing trillions of dollars around the world.

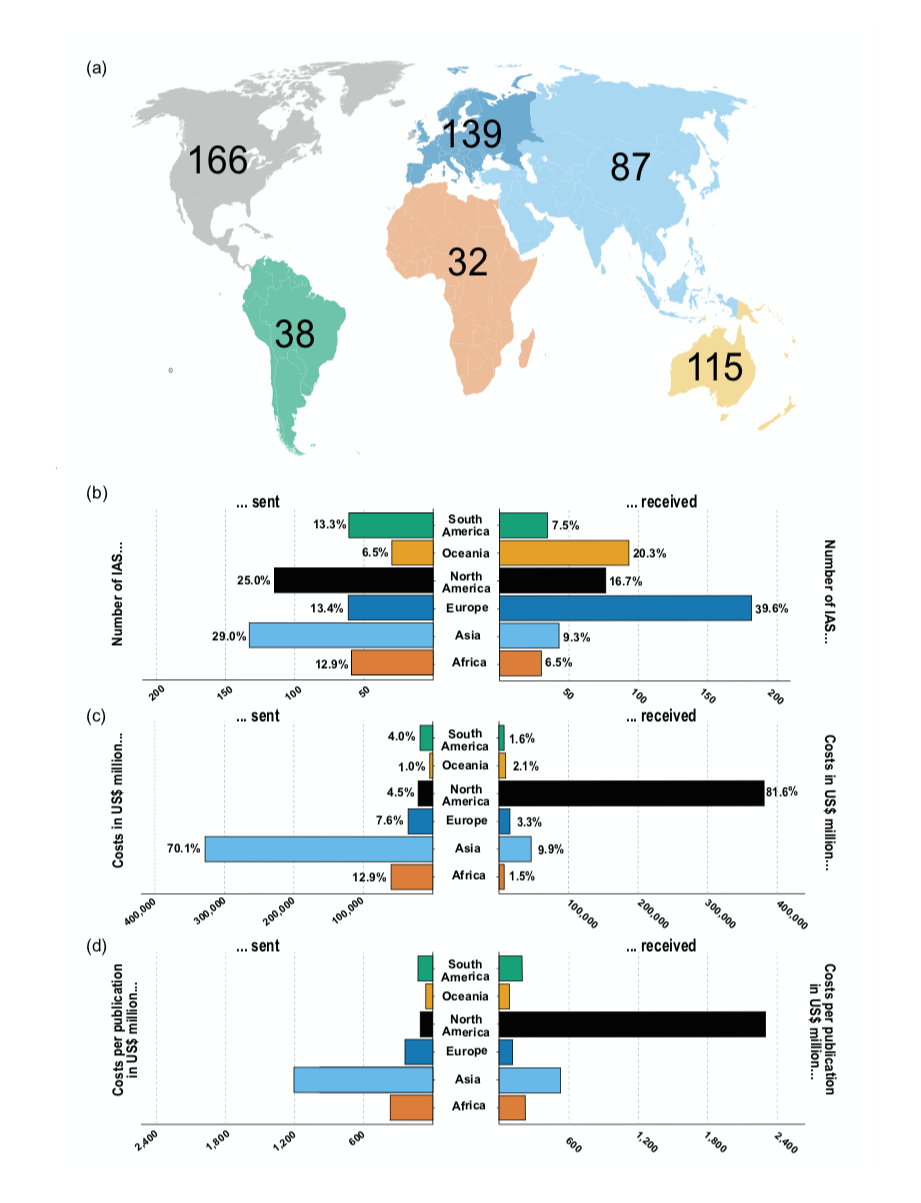

Our research shows that flows of economically impactful invasive species and their reported costs are unevenly distributed worldwide, with costs disproportionately reported in just a few regions, such as North America (Figure 2).

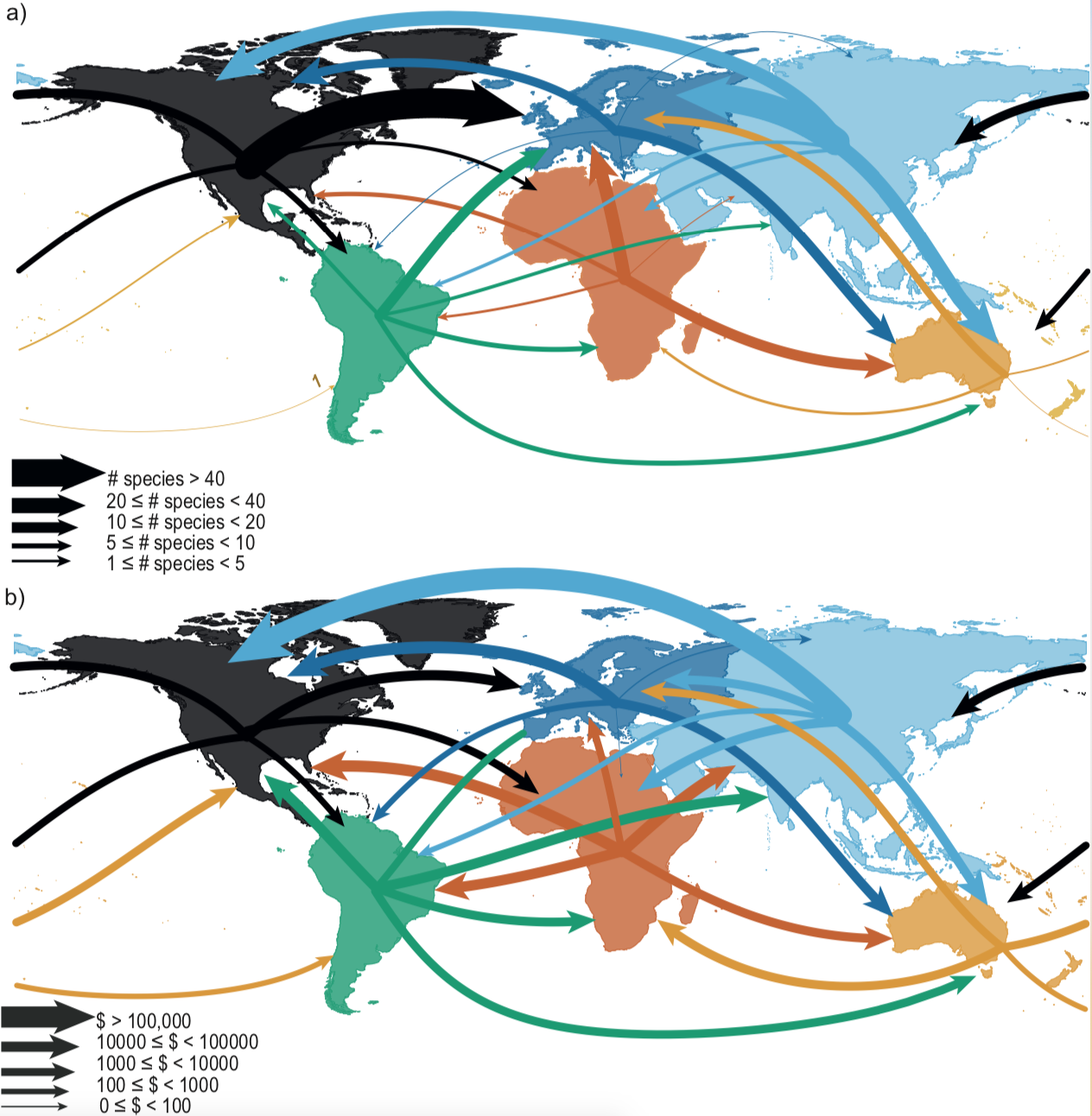

Our study used the publicly-available InvaCost database (https://invacost.fr), which compiles reported monetary costs of invasive species around the world and involves a multidisciplinary group of collaborators. We assigned the origin regions of costly invasive alien species, and examined which countries have paid these costs. We found that recorded costly invasive alien species have originated from almost all regions, most frequently causing impacts to Europe (where impacts were associated with 673 invasive alien species, Figure 3). In terms of cost magnitude, reported monetary costs predominantly resulted from species with origins in Asia impacting North America (totalling$ 319 billion measured in 2017US$ ).

This research also examined the drivers of cost flow dynamics between countries statistically. High reported cost flows between invasive alien species’ native countries and their invaded countries were related to proxies of similar climates and shared trade history, which can be partly attributed to the legacy of colonial expansion and past trade patterns. Therefore, costly biological invasions between country pairs were more likely if they had a history of trade or colonialism as well as shared environmental conditions, which promote arrival and success of alien species.

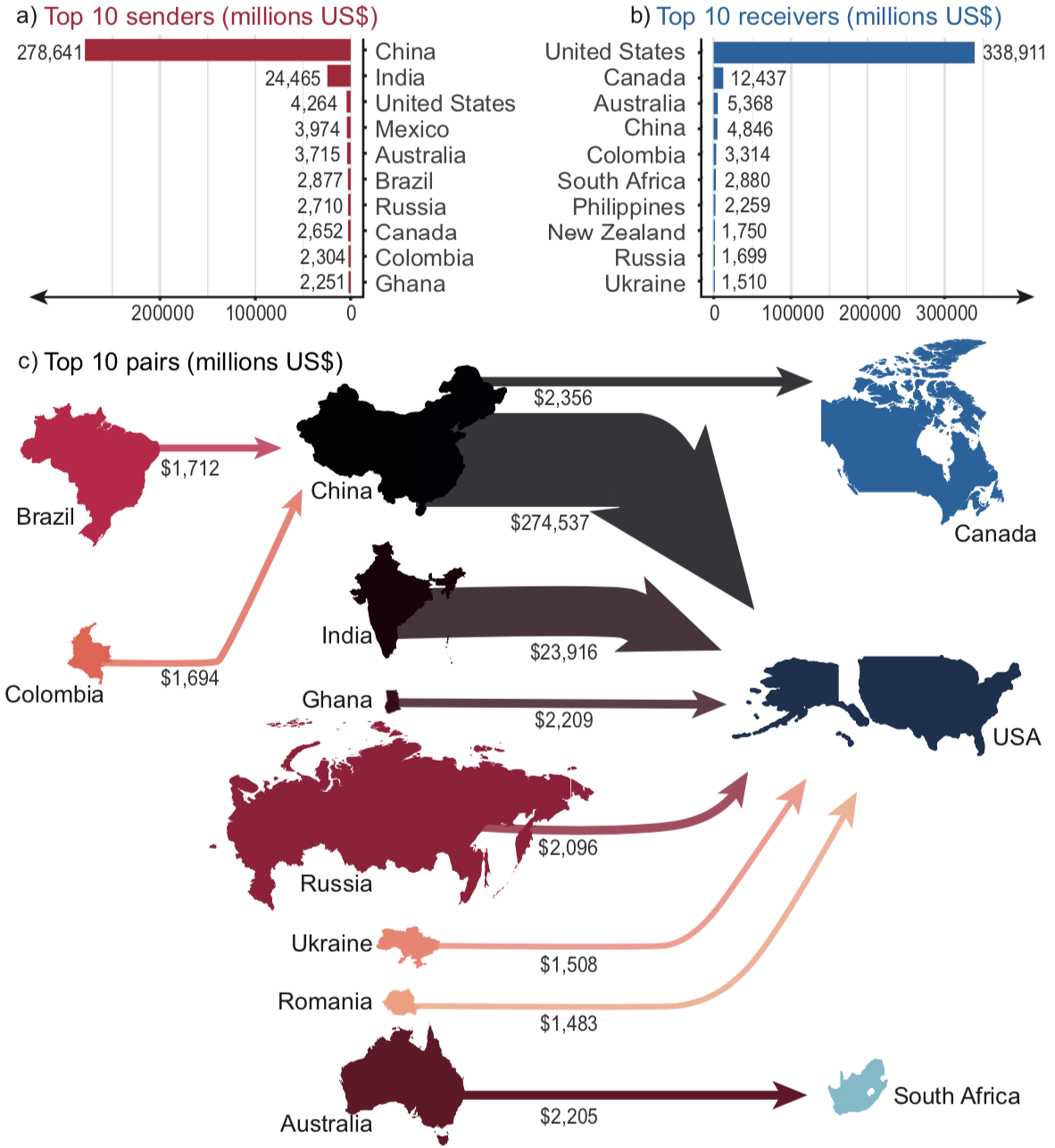

The country receiving the most reported costs was the USA (US$339 billion, Figure 3), although Colombia had the highest costs reported per publication (US$ 3.3 billion). Several countries appeared as both top senders and receivers (China, Canada, Colombia, USA, Australia, Russia; Canada and USA only when considering reported cost per publication). Some individual countries were pervasive sources of costly biological invasions, with flows from China and India to the United States particularly pronounced and reflecting trade intensities. However, these results should be viewed in the context of data availability, with cost magnitude reported in countries intuitively linked to research efforts to uncover these costs.

The characterization of ‘sender’ and ‘receiver’ regions of invasive alien species and their associated costs highlights the immense risks posed by alien species, and can be used to motivate prevention and early intervention in response to invasions, as well as the prioritization of control efforts across invasion routes. With the world becoming more interconnected and biological invasions being bolstered by climate change and habitat degradation, it is likely that these flows of costs will intensify in the future without more proactive management actions (e.g., biosecurity and timely eradication initiatives). These cost flows could hit less economically developed countries hardest in future, which have lower preparedness and capacity to mitigate and manage biological invasion impacts.

Our findings have important implications for policymakers, highlighting the need for a more coordinated global response to biological invasions. By identifying the regions and species that are most at risk, policymakers can take action to protect biodiversity and the sustainability of economies and societies.

This research has been published in Nature Sustainability and is available online (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41893-023-01124-6). All data and code associated with the research is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.7776447

For further information, please contact emma.hudgins@carleton.ca

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Sustainability

This journal publishes significant original research from a broad range of natural, social and engineering fields about sustainability, its policy dimensions and possible solutions.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in