Behind the scenes — from construct design to SAMURI 3D structures

Published in Protocols & Methods and Cell & Molecular Biology

The initial spark

Most methyl transfer reactions nowadays are carried out by protein enzymes, using the universal methyl donor S-adenosylmethionine (SAM). Following the discovery of the first methyltransferase RNA-based enzyme or ribozyme (MTR1), which installs an RNA modification (m1A) by recruiting O6-methylguanine as a cofactor, it’s now evident that RNAs, in addition to proteins, can also catalyze RNA methylation.1 Inspired by MTR1, we were confident that there must be ribozymes capable of using SAM for alkyl transfer reactions. Indeed, two SELEX-evolved ribozymes have shown alkylating activity in the presence of SAM: Jiang et al reported the first SAM-dependent ribozyme (SMRZ1) which methylates guanine (m7G).2 Shortly after, Höbartner’s lab identified another synthetic ribozyme, SAMURI, which alkylates adenosine (m3A / pro3A) using SAM or its derivatives as cofactors.3 Among these, the high alkylation efficacy of SAMURI particularly intrigued us, given that natural SAM-binding RNAs, SAM riboswitches, exhibit minimal activity toward methylation despite their strong affinity for the same ligand SAM — a strategy nature employs to avoid self-methylation. These contrasting behaviors of SAM riboswitches and SAMURI sparked the initial steps of our journey, leading us to determine the 3D structure of SAMURI through X-ray crystallography in order to uncover the fundamental structural differences between “reactive” and “unreactive” RNA when SAM is involved.

Don’t judge a book by its cover

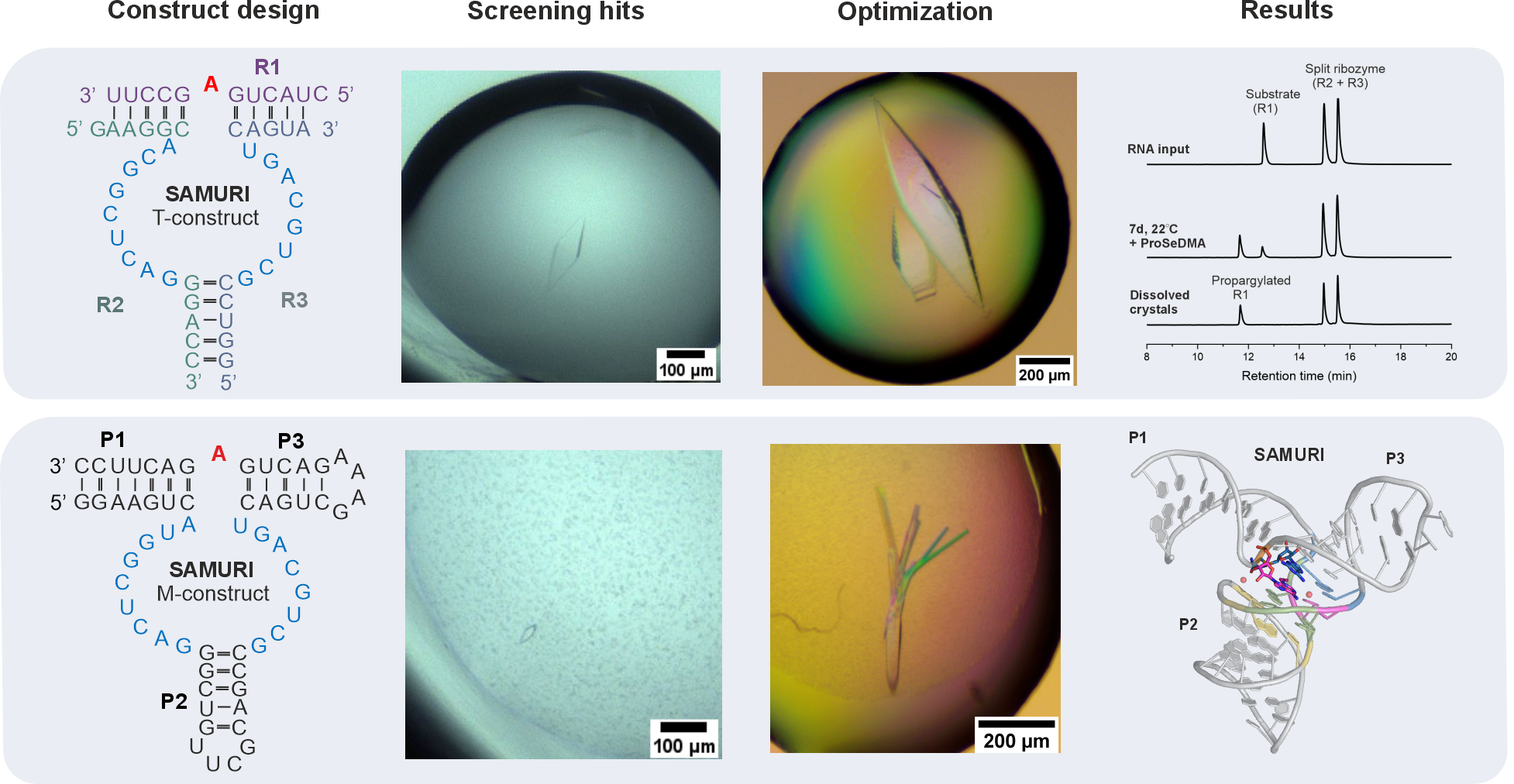

Obtaining well-diffractive crystals is the biggest hurdle for most macromolecules – this is especially true for RNAs due to their negatively charged backbone and the limited intermolecular interactions which are required for the formation of crystals. After extensive crystallization trials, two potential candidates emerged: a trimolecular (T) construct and a monomolecular (M) construct (Figure 1). While the T-construct readily grew huge, beautiful crystals, the M-construct formed tiny, diamond-shaped crystals that were difficult to reproduce. Based on the crystal morphology and our previous success in determining the MTR1 structure,4 we initially focused most of our efforts on improving the T-construct, with only minor attention given to the M-construct. The diffraction experiments, however, revealed their true quality that had been disguised. After optimization of both constructs, the M-construct eventually resulted in the final structure at a resolution of 2.9 Å, while the gorgeous-looking crystals from T-construct remained poorly diffracting. Nevertheless, the time invested on the T-construct was not spent in vain. It allowed us to characterize the crystal contents, which wasn’t possible for the M-construct. Anion exchange chromatography revealed a preference for the post-catalytic state in the SAMURI crystals, despite the presence of over 30% unmodified species in the crystallization drop. Similar results for the M-construct were obtained indirectly via gel-shift assays, as shown in the paper.5

Figure 1. Construct design and results. Upper panel: trimolecular (T) construct generated beautiful crystals that barely diffracted; only propargylated substrate was present in the anion exchange chromatograms of dissolved crystals. Lower panel: tiny crystals of the monomolecular (M) construct were optimized, eventually leading to the final 3D structure.

The breakthrough moments

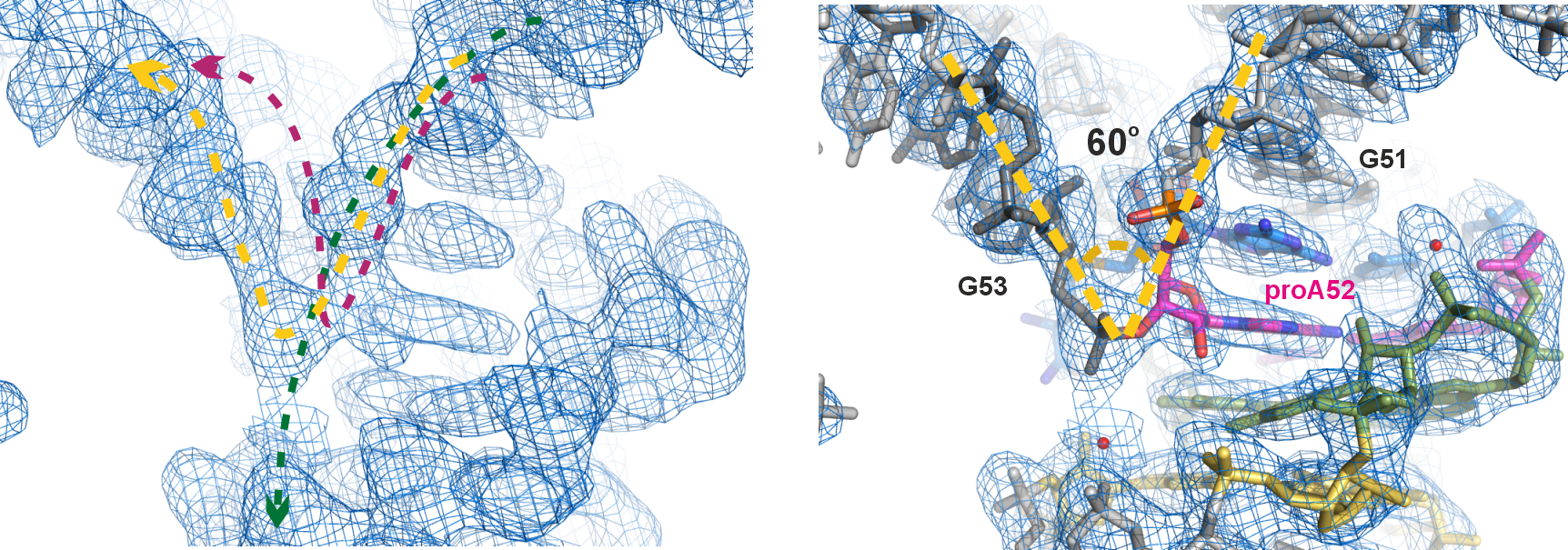

After diffraction experiments, the phase problem was solved using single-wavelength anomalous diffraction (SAD), resulting in a partial map that encompassed the electron density of the catalytic core and the bound cofactor. Manual tracing of the RNA substrate strand revealed a surprising kink at the active site – a 60o sharp turn within three consecutive nucleotides (Figure 2). Although such kink motifs are occasionally encountered in structured RNAs, we were very prudent in modeling it, especially given that the initial density was rather intermittent around this region. Several attempts to re-model this moiety differently (green and magenta dashed lines, Figure 2 left) only deteriorated the fit to the density and violated chemical restrains. Only modeling of the kink yielded satisfactory results as shown in the final model (Figure 2 right). This further demonstrated the versatile 3D structures RNAs can adopt, which enable their specific functions. In the case of SAMURI, the in vitro evolution has chosen an unexpected tertiary structure – the kink – to place its substrate in the proximity of the cofactor, thus ultimately facilitating the alkyl transfer reaction.

Figure 2. The unexpected kink at the active site. Left panel: electron density map of the final model, zoomed-in near the active site (contoured at 1σ); the dashed lines depict three possible paths of the RNA chain, with the yellow line representing the final model. Right panel: final model built into the electron density map. Instead of the usual linear twist of A-form helical structures, the active site adopts a 60o sharp turn (kink) within a 3-nt long stretch (G51-proA52-G53).

Hunting the hidden

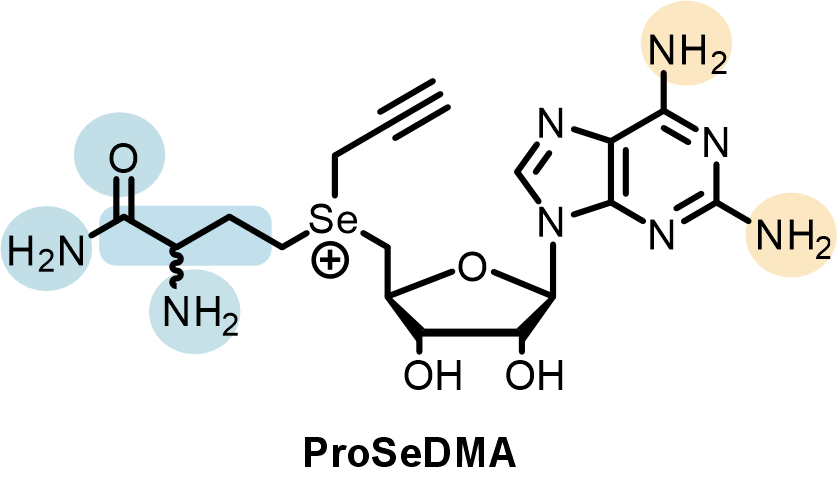

In the SAMURI crystal model, every nucleotide in the catalytic core affords one or more functional roles to stabilize the overall architecture or to facilitate the correct orientation of active center, except for two nucleotides, A7 and U8, which do not interact with any nearby residues. These nucleotides were initially termed “spacer” and considered to merely provide sufficient space rather than directly participate in the catalysis. Yet chemical structure probing and ribozyme mutagenesis experiments suggested a potential interaction between U8 and the cofactor. To identify the U8 interacting partners in the cofactor, we synthesized a series of cofactor “mutants” (Figure 3), examined their influence on SAMURI catalysis, and finally successfully pinpointed the α-amino group in the methionine unit as the most likely hidden interactor with U8. Taken together, what was initially considered a “nonessential” spacer nucleotide turned out to be an activity booster. Another surprising discovery in the cofactor campaign was a cofactor variant ProSeDM, which lacks the entire methionine unit but still served as an alkyl donor. For more detailed biochemical characterization and the discussion of ProSeDM, please visit our paper.

Figure 3. Systematic variation of the cofactor. Atomic mutations in the methionine moiety (blue) and the nucleobase (orange) were assessed individually via kinetic assays.

Looking back to nature

Building on the solved structures of SAM riboswitches, our determination of the SAMURI structure adds another crucial piece to the grand puzzle of SAM-dependent functional RNAs. Returning to the motivation behind this project, we compared SAMURI to all classes of SAM riboswitches to decipher the structural basis of their distinct functional roles. The proposed mechanism of SAMURI suggested a proximity-driven approach, following an SN2-like pathway that does not require activation by a general acid, base or metal ions. Our studies suggest that SAMURI differs from SAM riboswitches in two key aspects: first, SAMURI avoids the neutralization of the positively charged chalcogen center by nearby uracils, which is a common strategy observed in riboswitches to prevent self-methylation. Furthermore, SAMURI arranges the nucleophile and the electrophilic carbon in an in-line orientation that favors the alkyl transfer reaction. Altogether, our recent report in Nature Chemical Biology not only provides critical insights into SAMURI catalysis, but also highlights the structural features of different functional RNA systems, offering a plausible answer to a long-standing question.

References

- Scheitl CPM, Ghaem Maghami M, Lenz AK, Höbartner C. Site-specific RNA methylation by a methyltransferase ribozyme. 587(7835):663-667 (2020).

- Jiang H, Gao Y, Zhang L. et al.The identification and characterization of a selected SAM-dependent methyltransferase ribozyme that is present in natural sequences. Nat Catal 4, 872–881 (2021).

- Okuda T, Lenz AK, Seitz F, Vogel J, Höbartner C. A SAM analogue-utilizing ribozyme for site-specific RNA alkylation in living cells. Nat Chem. 15(11):1523-1531 (2023).

- Scheitl CPM, Mieczkowski M, Schindelin H, Höbartner C. Structure and mechanism of the methyltransferase ribozyme MTR1. Nat Chem Biol. 2022;18(5):547-555.

- Chen HA, Okuda T, Lenz AK, Scheitl CPM, Schindelin H, Höbartner C. Structure and catalytic activity of the SAM-utilizing ribozyme SAMURI. Nat Chem Biol (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41589-024-01808-w

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Chemical Biology

An international monthly journal that provides a high-visibility forum for the chemical biology community, combining the scientific ideas and approaches of chemistry, biology and allied disciplines to understand and manipulate biological systems with molecular precision.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in