Biology’s snowflakes: why fractal patterns in human kidney cells matter

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology, Materials, and Biomedical Research

Fractals are defined as objects that are self-similar over multiple scales. Zooming-in on a fractal object reveals finer structures that are self-similar to the structure of the fractal object at a larger scale. Tree branches and snowflakes are fractal objects that most of us are very familiar with. Beginning in the 1970s with Benoit Mandelbrot’s foundational work on fractal geometry, fractal patterns have gone on to mesmerize scientists and permeate popular culture. Fractals fundamentally changed how we interpret complex systems, underpinning advances from realistic digital landscape animation and image compression to models of financial market crashes.

It turns out that nature often follows fractal rules when building complex structures in either space (e.g. mountain ranges) or time (e.g. hurricanes). Fractal structures are common in biological systems in either space (e.g. lung alveoli) or time (e.g. heart rate variability). Fractality has long been recognized in the cardiovascular system. For example, the branching structure of the circulatory system, consisting of arteries, arterioles, venules and veins, is considered to be fractal, because it exhibits self-similarity over multiple length scales, from cm to tens of mm. As we zoom-in on the vascular tree, the branching pattern is maintained, up to the level of capillaries that are regular arrays of cylinders.

Yet to date, fractal patterns in tissue systems have been viewed primarily as descriptive features of geometric complexity, with little understanding of whether fractal organization plays an active role in directing tissue behavior. In addition, fractal complexity has not been appreciated in the kidney, or its main filtration unit, the glomerulus. The kidney glomerulus is a specialized microscopic structure in the kidney that performs the first step of blood filtration. Its role is to get the waste products such as urea out of the blood, while retaining highly valuable protein molecules such as antibodies. This selective barrier function is afforded by specialized epithelial cells, podocytes which form a layer wrapping around a looping capillary in the glomerulus. Their selectivity comes from their highly branched morphology. Their finger-like membrane protrusions interdigitate with those of other podocytes in the layer to form a barrier of appropriate selectivity. Once those finger-like protrusions are lost, a person may suffer a kidney disease. Podocytes are often a site of drug induced toxicity, which also compromise the barrier function by decreasing podocyte interdigitation.

Achieving a highly branching podocyte morphology and appropriate gene expression has been a major bottleneck for numerous researchers for several decades. All conventional culture systems yield poorly branching cells that generally do not express podocyte markers such as nephrin. This is a major impediment for both kidney disease modelling and drug development. In fact, pharma companies have reached out to our team motivating the development of the improved culture system. Previously, we tried to use our 1D AngioChip platform (Zhang et al Nature Materials 2016) to cultivate podocytes around a vascular tube, without much success in driving the branching morphology formation. Cells on 1D AngioChip looked akin to those on flat substrates, spindle shaped and not fractally branching.

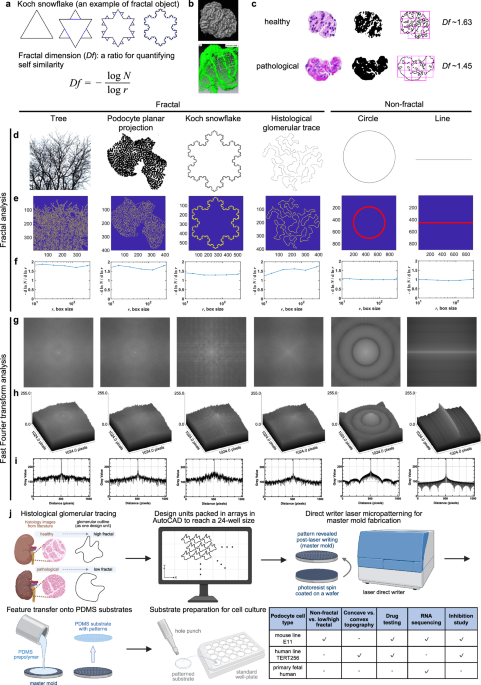

In our latest study, we set out to answer exactly that question—using fractal geometry inspired by the native architecture of the kidney glomerulus. We first delineated and established fractality glomerulus structure, by fractal analysis of histological images from healthy and pathological mouse glomeruli, as well as human samples. This analysis also revealed a reduction in fractal dimension in diseased states.

To ask whether podocytes and glomeruli are truly fractal, we compared their outlines to classic fractal objects—a branching tree and the Koch snowflake—and to non-fractal controls such as a straight line and a perfect circle. Using box-counting and frequency analysis, we found that both podocytes and glomeruli display non-integer, multi-fractal behavior and lack a dominant spatial frequency, closely mirroring canonical fractals rather than simple geometries. Together, these analyses confirm that fractality is an intrinsic feature of mature podocyte morphology and glomerular architecture, which we then distill into a single representative fractal dimension for scaffold design in the remainder of the study.

We then developed a fractal culture platform by replicating the fractal dimension from histologies of human and mouse glomerulus. These histological outlines were turned into CAD files, that enabled us to generate topographical substrates using cleanroom fabrication techniques. We engineered surfaces with increasing degrees of fractal complexity and asked how podocytes respond. The answer was striking: the more fractal the environment, the more mature and complex the cells became.

Podocytes grown on our fractal scaffolds formed many orders of branching, closely resembling their native morphology, and showed dramatically enhanced gene expression compared to conventional flat or non-fractal culture systems. Importantly, these effects were consistent across three distinct podocyte sources, demonstrating that the response was not cell-line specific but driven by the geometry itself.

Digging deeper, we uncovereded the mechanism behind this effect. Fractal topographic cues promoted a hierarchical assembly of cellular structures that drove podocyte branching through YAP signaling, linking physical geometry directly to intracellular pathways controlling maturation. Beyond basic biology, the platform also proved highly practical. Podocytes cultured on fractal substrates displayed more physiologically relevant responses in drug testing assays, highlighting the system’s potential for disease modeling and drug screening. To ensure real-world applicability, we translated the fractal designs into commercially compatible well plates by hot-embossing thermoplastic elastomers—fully eliminating the need for drug absorbing polydimethylsiloxane and enabling scalable manufacturing.

Together, this work shows that fractality is not just a descriptive feature of biological tissues, but a powerful, previously untapped design principle for guiding cell maturation. By engineering geometry itself, we open new possibilities for building more faithful in vitro models of complex organs like the kidney.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Excellent Work