Buried landslides and landscapes

Published in Earth & Environment

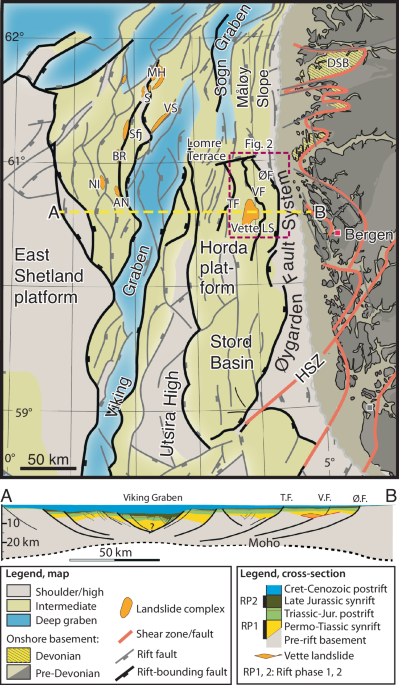

Some 15-20 years ago we were interpreting scattered 2D seismic sections where interesting information about the deep parts of rift basins could be seen. However, connecting and interpreting this information in three dimensions was difficult. I was repeatedly puzzled by a particular seismic image in the northern North Sea rift off the Norwegian coast, where the dip of one of the main rift faults, known as the Vette fault, was much lower in one particular section than in parallel neighboring sections, and much lower than what was normally seen in this rift. This really triggered my interest, but with a ~10 km line spacing looking for an explanation was like fumbling around in the dark.

The light was turned out when the company CGG, now Viridien, collected the NVG 3D seismic data cube. Commercial 3D seismic cubes have been around for decades, but this one (NVG) was a huge and consistent broadband survey that imaged the deeper parts of the rift basin and not only the higher levels that contain hydrocarbon reservoirs and reservoirs used for CO2 sequestration. The base of the sedimentary basin stood out clearly as a surface that was mappable in three dimensions in an unprecedented way. And the good news was that it was made available to academic researchers at no cost. Getting our hands at this dataset in 2018 was like starting a long-lasting academic party.

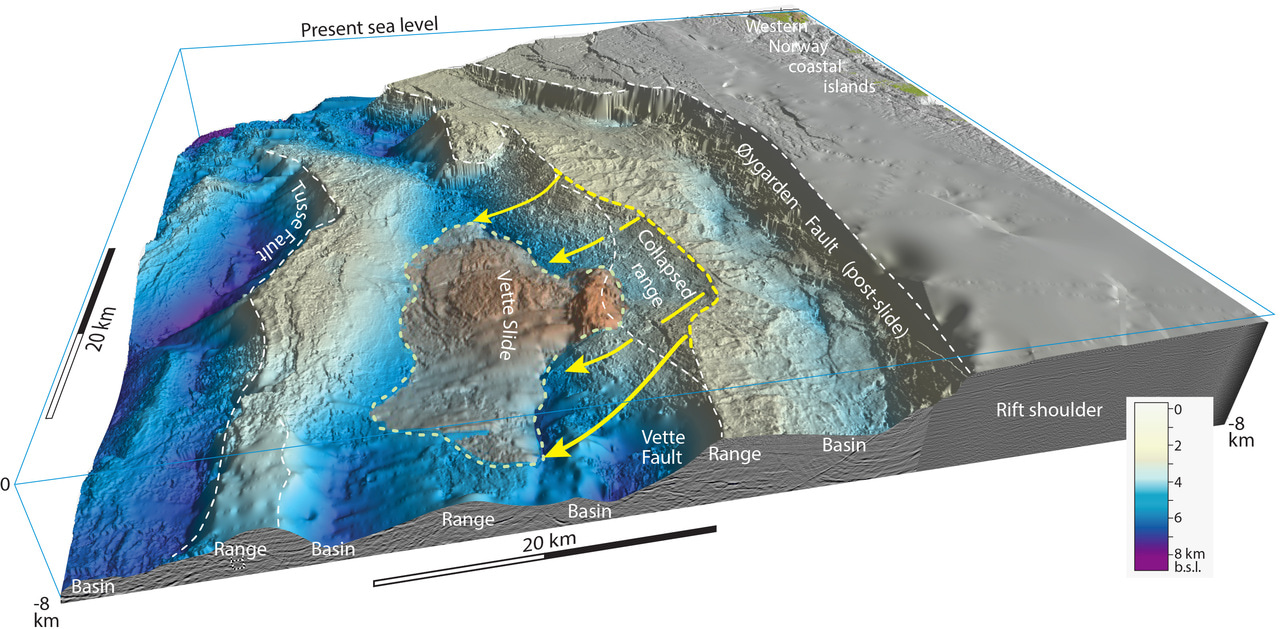

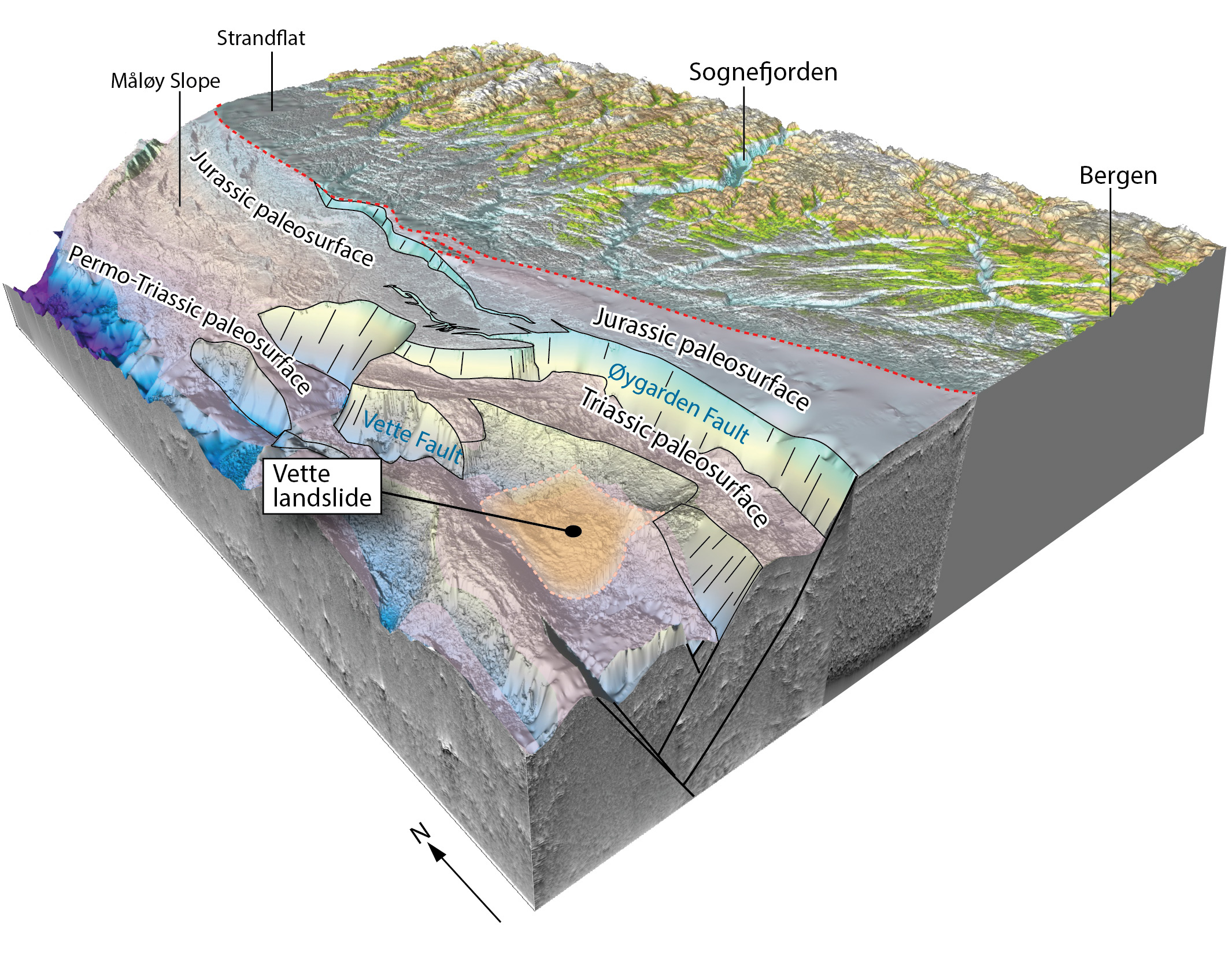

It was now possible to virtually travel around and, among other things, inspect what was the surface of the Earth a couple of hundred million years ago in the last part of the Permian time period (Figure 1). That early rift landscape seems to have developed fast. Over a few million years it developed from a low-relief and rather even surface to a Basin and Range-style topography governed by fast-moving rift faults and associated earthquakes. In the Basin and Range of the western US, basins between the ranges are filled with sediments. So also in the North Sea rift, but not so much in the beginning. In fact, it was surprising to see that the region was highly sediment starved during the first part of the rift evolution. And the reason we know this is the discovery of an enormous landslide deposit resting on the buried pre-rift surface of crystalline crustal rocks.

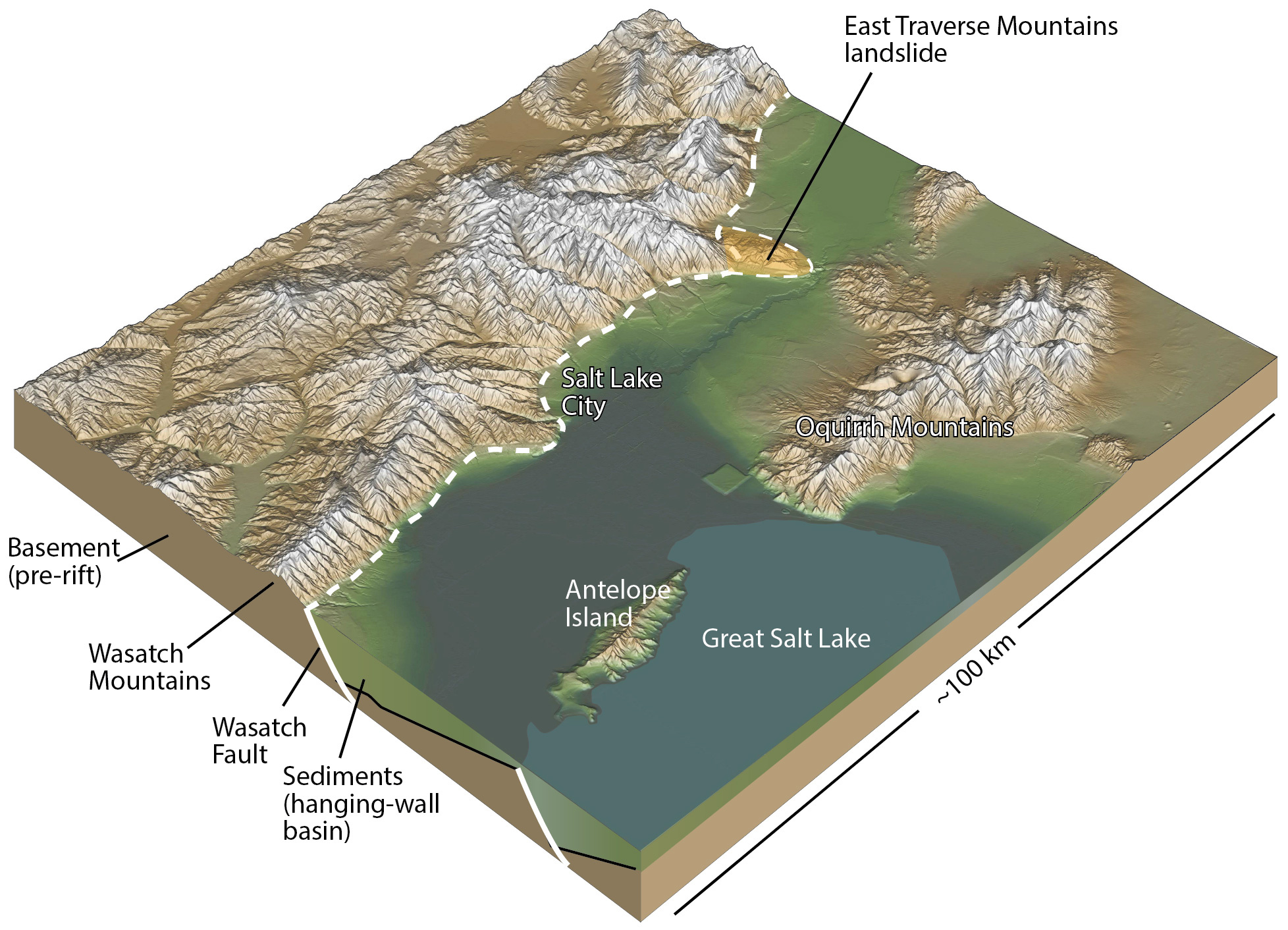

That takes us back to the low-angle fault observation above. With the new data I realized that the low-angle fault was not the original Vette rift fault, but a secondary detachment fault that cut into the footwall mountain range to create a huge landslide. An estimated 300 km3 of the range moved down the detachment fault and onto the hanging wall as the range collapsed. The first important observation is that the slide is up to 2500 meter thick in its middle part. Such a thick slide must have come from a mountain range that was even higher, with a relief on the order of 3000 meter. For comparison, the maximum relief in Death Valley, situated in the Basin and Range province, is 3455 meters, while the Wasatch Mountains near Salt Lake City rises 2000 meters above the valley. However, the Wasatch mountains are deeply eroded with complementary deposits in the hanging-wall basin (see Figure 2), so the structural relief or total Basin and Range related fault offset is much larger.

The other important point is that the slide virtually rests directly on the old top-basement surface, i.e., the pre-rift landscape. With no sediments between the slide and this surface, I realized that erosion of the Vette footwall range must have been very modest, which is compatible with a very dry climate. The Atacama Desert in northern Chile is such a dry place with hardly any precipitation and with landscapes that have been well preserved through millions of years. The hanging-wall side of the Vette fault developed into a deep hole, as the footwall uplift created a mountain range. Usually, mountain ranges do not collapse along a stretch of tens of kilometers, because they are broken up by fluvial channels (valleys that separate local mountain peaks. This is the case with the Wasatch Mountains, which is why its largest associated landslide, the east Traverse Mountains landslide, are much narrower both in terms of absolute value (6 km) and relative to its length (see Figure 2). In our North Sea case, the Vette mountains had maintained a rather even altitude along the fault for a long stretch. Again, this can be related to a very arid climate without much water/river erosion. Then we see that this early-rift landscape becomes buried under thick piles of sediments, which makes us believe that the climate became less arid as we move into the Triassic period. Everything got buried and preserved, thanks to the lowering of the whole system by a new fault that developed closer to the Norwegian mainland (the Øygarden Fault).

The Vette landslide is the largest landslide discovered in any rift, current or ancient. Its discovery shows that huge landslides can occur in a rift environment. But if we look around in modern rifts, including the Basin and Range, most slides are much smaller. It is very unusual to have a huge portion of a mountain range collapse like we see in our ancient North Sea rift case. Apart from climate, there are two other important factors to be considered. One is the size of earthquakes rattling the mountain ranges. Clearly the mountain ranges are located next to large faults, so they are bound to shake as the fault moves. But faults show different behaviors. Some move by multiple small and some intermediate events, while others can accumulate a higher stress level before rupturing and thus create large earthquakes. Perhaps the Vette fault was of the last kind. This is difficult to prove. The other factor is easier to deal with. That is the presence of optimally oriented weak structures (faults or fracture zones) that makes the mountains less stable. The seismic data reveals such a structure exactly where the Vette detachment formed. I believe this was one of the prerequisites for creating this huge landslide.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in