Introduction: Science fiction writers have long toyed with the idea that the human mind is susceptible to new ideas during sleep. And until recently, “learning by osmosis” was considered just a wishful fantasy. Yet in the past few years, a torrent of surprising studies is suggesting that the sleeping human mind may, in fact, be a fantastic learning machine...

It sounds like the ultimate life-hack: you cozy up in bed, plug in your headphones, and drift off to sleep with French lessons softly whispering in your ear. The next morning, you wake up refreshed, with a bonus perk of having a few new French words added to your vocabulary.

Feeling skeptical? You’re not alone. Science fiction writers have long toyed with the idea that the human mind is susceptible to new ideas during sleep. And until recently, “learning by osmosis” was considered just a wishful fantasy.

Yet in the past few years, a torrent of surprising studies is suggesting that the sleeping human mind may, in fact, be a fantastic learning machine. It’s a controversial but powerfully alluring idea. And like many extraordinary neuroscience discoveries, the story starts in a lab, with a mouse navigating a winding maze.

Of Ripples and Waves

Roughly three decades ago, a team of scientists stumbled across a curious phenomenon while studying how rodents learn to navigate a new space.

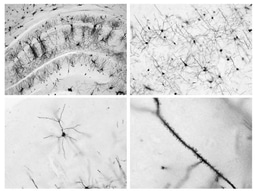

The focus, at the time, was on a group of so-called “place cells,” which lie in a seahorse-shaped structure—the hippocampus—deep within the brain. Similar to GPS coordinates, these cells fire in sequence as a mouse learns to route its way through a maze towards a food reward.

The surprise came later in the day, when the mice dosed off into a deep stage of sleep dubbed slow-wave sleep (SWS). During this stage, the brain’s electrical activity slowly cycles in peaks and troughs like the ocean’s waves. Yet curiously, sharp busts of electrical activity periodically punctured these lazy cycles—activity that intriguingly looked like the place cell activation patterns from the previous day played in fast-forward.

Could the hippocampus be rehearsing its winning trajectory over and over while the animals slept?

When the scientists disrupted these electrical “ripples”, the mice’s memory faltered. This discovery led to one of the most important ideas in the neuroscience of memory: that new memories are fragile and easily forgotten, but sleep helps choose the important ones and etches them in place, a process dubbed “memory consolidation.”

The idea of sleep as a natural memory aid soon caught on, and scientists around the world began testing the limits of its effect on memory.

Back in 2007, an ambitious study with medical students convincingly showed that familiar scents can reactivate—and strengthen—memories from the day before. In the study, the volunteers were asked to recall the location of card pairs on a computer screen. Whenever successful, the scientists puffed a burst of rose-scented air into their face.

Half an hour later, the students napped while wearing an EEG cap embedded with electrodes that monitored their brain activity. Here’s the trick: whenever the scientists detected that the students were in SWS, they once again puffed some of that rose-scented air to half of the sleeping students as a memory cue. It made a difference: upon waking, those that smelled the rosy scent in their sleep performed 15% better than those who did not.

A similarly impressive demonstration came five years later. A group of instrument novices learned to play a simple melody on a piano before they drifted off to sleep in a lab. Half of the learners heard the melody playing on repeat as they slept—and compared to those who didn’t receive the cue, they made far fewer mistakes when asked to perform the piece after awakening.

The most mind-boggling study of them all? A group of German speakers listened to Dutch while they slept. And yes—they remembered new Dutch words better than those who weren’t exposed to those words during the nap.

Sci-fi writers may have had it right all along.

Sleep Inception

The above studies, and many more, clearly show that sleep strengthens memories from the day before. But a study from 2015 rocked the field by expanding the learning boundaries of the sleeping brain.

Here’s how it went: a team from Paris recorded the activity from single place cells as a mouse explored a circular chamber. Then, as it slept, the clever scientists waited for those cells to go through their nightly rehearsal.

Picking a single place cell, the team artificially stimulated the reward center of the mouse’s brain as it reactivated, in essence forming a completely false association between that cell (and the location it encodes) with a sense of pleasure.

Guess what? When the mouse woke up, it dashed towards that precise location, likely in hopes of getting another dose of pleasurable feelings.

Rather than strengthening a previously learned memory, here the team had incepted a new memory into the sleeping brain.

These surprising results were soon bolstered by a human study. Working with a group of smokers, this team wondered if linking something nasty—say, the smell of rotten eggs—to cigarettes could help the volunteers kick their daily habit.

To an extent, the idea worked. Those who sniffed a combination of cigarette smoke and a foul odor while they slept smoked roughly 30% less on average the following week. Notably, the team didn’t include long-term follow-up, so we don’t know how long these results lasted. But remember: for the smokers, this was an easy way out. Without any conscious effort or intention on their part, they experienced a drop in cigarette cravings.

Dream On

What all this suggests is that it is possible to strengthen learning in sleep, at least for some types of memories. We’re really just scratching at the surface. The benefits could be enormous—veterans could encode new, pleasant memories during sleep to battle their PTSD. Addicts may override their rewarding memory of drugs with something healthier.

And for the rest of us battling hectic schedules in our day-to-day, maybe sleep could provide precious bonus time to learn a new skill or master a new craft.

Yet we should also ask: does sleep-learning come at a price? After all, if we’re artificially enhancing certain memories (and the synapses that store them), are we inhibiting other memories from their natural consolidation.

What’s more, sleep isn’t just about memory. Last year, scientists found that sleep kicks the brain’s sewage system into high gear, ridding our brains from harmful metabolic waste. Could we, by tampering with sleep’s natural rhythms, unknowingly disrupt this and other processes?

Without doubt, sleep-learning is the new frontier. And while many questions remain, I have to admit that I press play on a language-learning podcast or two before bed.

Now, would you?

Follow the Topic

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Shelly, thanks for sharing this. I'd heard some of this before, but you compiled a nice range of studies! Very helpful!