Can tracing a line help diagnose Alzheimer’s disease?

Published in Neuroscience, General & Internal Medicine, and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

Background

Every three seconds, someone in the world develops dementia. Alzheimer's disease (AD) is the most prevalent cause of dementia, accounting for 60-80% of cases. The European Medicines Agency (EMA) recently authorized lecanemab, a novel medication that targets the amyloid-beta, a protein linked to AD progression. However, lecanemab is recommended only in the early stages of the disease, such as Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI). This underscores the pressing need for improved ways to diagnose AD in its early stages.

The diagnosis of MCI is primarily focused on examining abilities like memory, attention, reasoning, and so on. However, an important aspect often remains overlooked: the visuomotor function.

Consider, for example, the act of reaching for a coffee cup. This task requires locating your hand in space, identifying the cup and any potential obstacles to the movement, understanding the mechanical properties of the object (shape, size, texture), planning the movement, and making adjustments along the way to optimize efficiency—all in the blink of an eye! Despite its apparent simplicity, this process is remarkably complex.

Surprisingly, research on visuomotor function in MCI is scarce. This is puzzling as people with MCI seem to struggle with these tasks even before more severe symptoms become apparent.

Our study

We wanted to find out if simple reaching movements—especially with distractors around—could help detect MCI in individuals at risk of developing AD dementia.

Who took part?

Three groups: (1) individuals with MCI due to AD, (2) healthy older adults, and (3) healthy younger adults. All were right-handed.

What did they do?

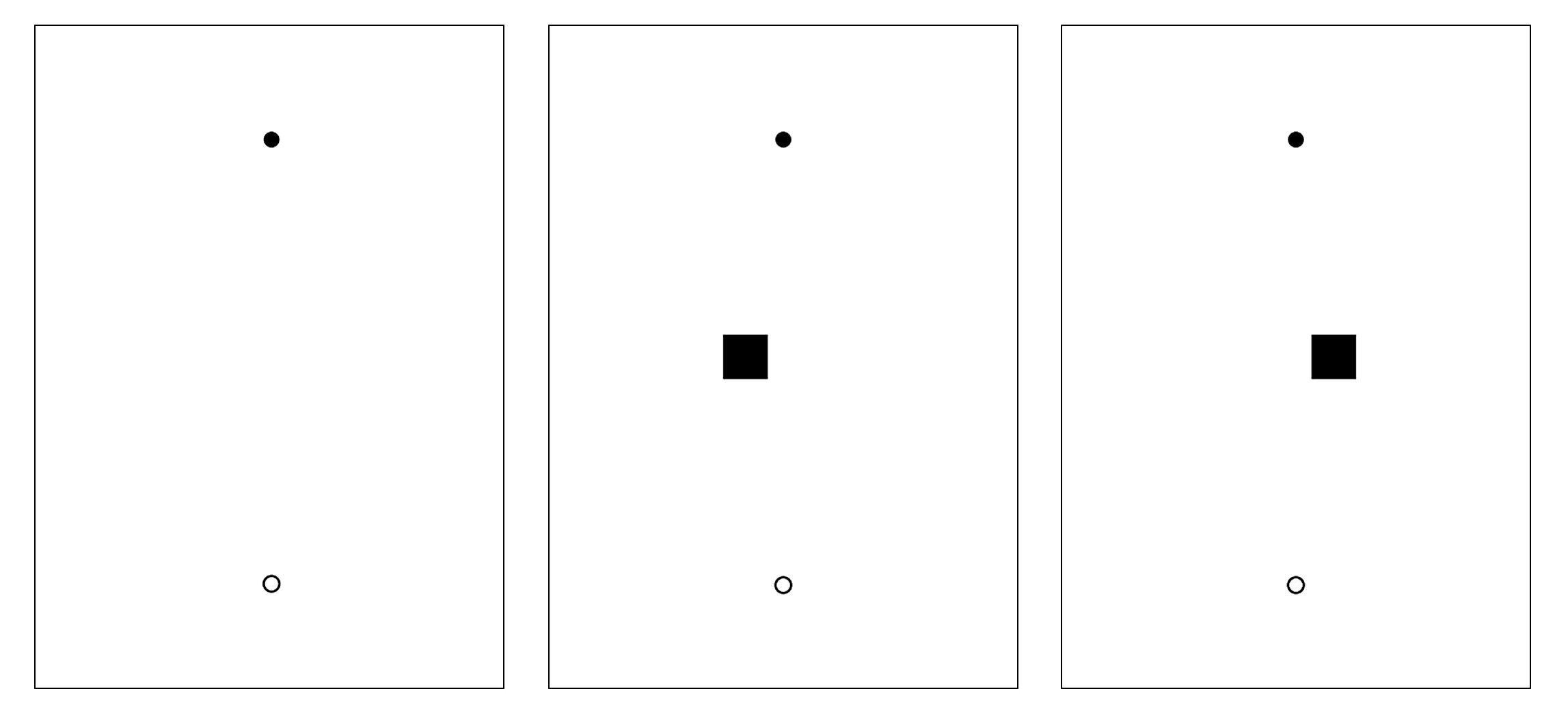

Participants used an electronic stylus to point from a starting dot to a target dot on a digitizer. In certain conditions, a distracting shape (the “flanker”) was presented at varying distances partway along their movement. Each participant completed two blocks of trials: one with the right hand (where the flanker, if present, was on the left) and one with the left hand (where the flanker, if present, was on the right). Participants were instructed to avoid “touching” the flanker during their movement.

The role of visual distractors

The brain can become “confused” when two objects compete for attention. The flankers were larger than the target to increase their “salience” and make them more difficult to ignore, while their placement at different distances modulated the level of challenge. By varying the position of the distractor, we could observe how participants adjusted their movements in real time.

Key findings

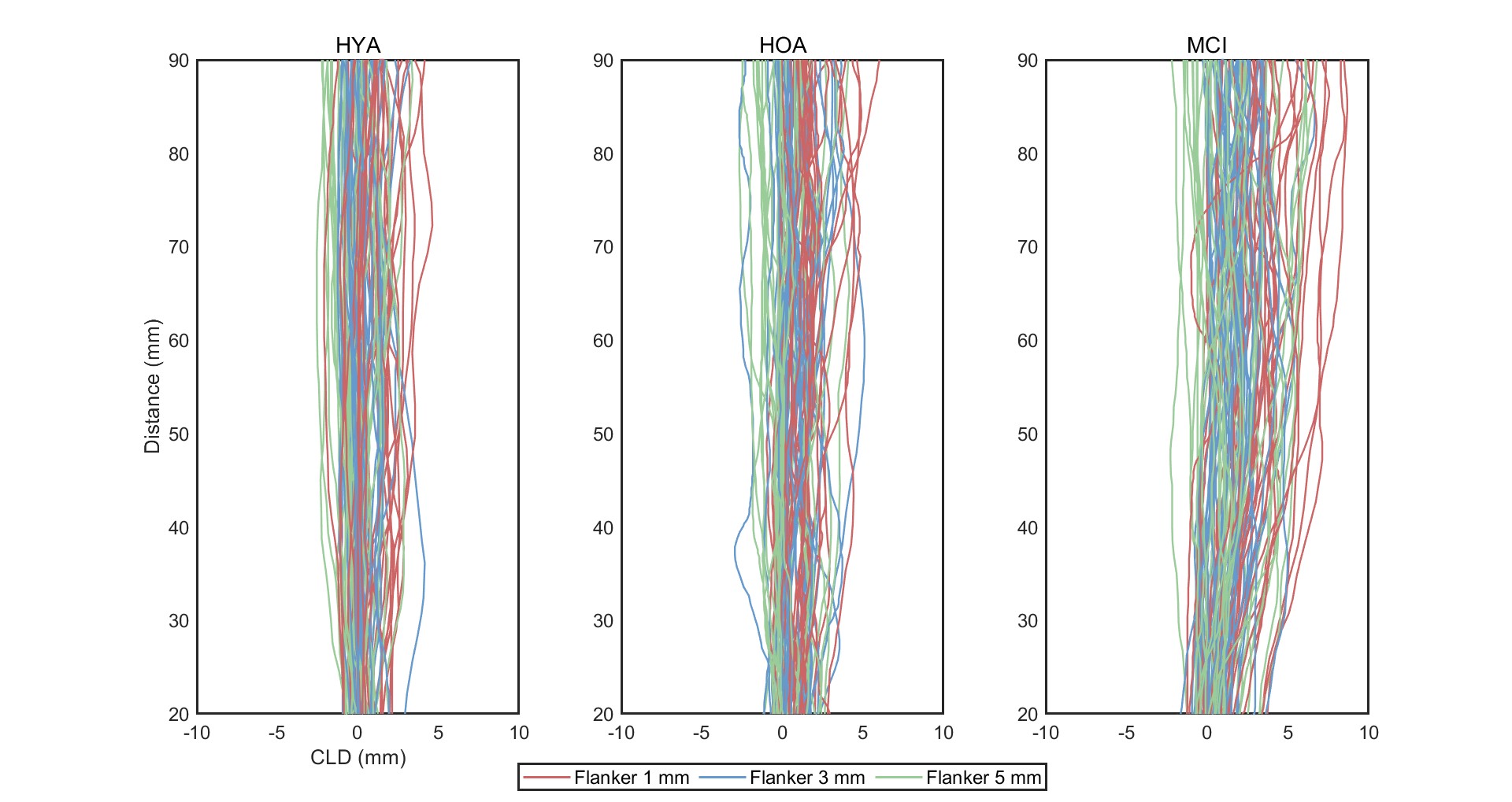

- Only the dominant (right) hand showed relevant differences.

- All participants exhibited significant rightward shifts in their movement trajectories when a flanker was present. The closer the flanker was to the path, the greater the trajectory amplitude.

- Participants with MCI showed less consistent and wider trajectories compared to healthy ones, especially when a flanker was placed very close to the path.

- When the flankers were farther away, participants with MCI showed “returning” trajectories, indicating that their fundamental mechanical abilities remained somewhat intact.

Discussion

In people with MCI, difficulty filtering irrelevant information may increase their sensitivity to distractors, likely due to abnormal activity in key brain regions such as the parietal cortex. While they could still adjust their movements to avoid collisions with the flankers, their actions were less consistent, suggesting some troubles in coordinating eye-hand movements. This may reflect a dissociation between preserved technical-mechanical skills and impaired movement planning. Interestingly, only the dominant hand showed disruptions in the visuomotor function. This was a curious result. The right hemisphere ages faster than the left, possibly affecting how it processes information in the left visual field. However, since each hemisphere primarily controls the opposite hand, our findings may indicate that the left hemisphere has reduced motor control over the right hand in people with MCI.

Future directions

The subtle visuomotor deficits we found may serve as a potential early warning sign of AD. Our findings suggest that testing visuomotor abilities using a simple reaching task might become an accessible, noninvasive method for the early detection of dementia. Our reaching paradigm may be translated into a smartphone or tablet app, making it quick and easy to evaluate visuomotor skills in clinical settings or even at home.

Follow the Topic

-

Scientific Reports

An open access journal publishing original research from across all areas of the natural sciences, psychology, medicine and engineering.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Reproductive Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 30, 2026

Women’s Health

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in