Transnational environmental crime (TEC) is a social issue closely linked to sustainable development and human security; it is an interdisciplinary phenomenon with implications far beyond plants, animals, and ecosystems. The United Nations Children’s Fund and others estimate TEC undermines development prospects for approximately one-third of the earth’s population of 7.7 billion people. TEC is systematic and continuous: illegal mining, logging, and fishing all destroy ecosystem resilience and diminish community access to natural resources. Toxic waste dumping harms children’s mental development; illegal wildlife trade can spread emerging infectious disease and invasive species; carbon fraud harms future generation's ability to adapt to climate change. And the links between TEC and violence, including the murder of environmental activists, are strong and increasing.

Science and scientists, natural, physical and social, play an essential role in helping to define the problem and describing solution spaces for decision-makers. Ignoring the impacts of TEC on sustainable development frameworks is to ignore opportunities for thinking about, talking about, and addressing harms to socio-environmental systems. Ultimately, this may result in a mismatched science-policy interface in a rapidly changing global economy with diverse harms to people and communities.

Over the course of approximately two years, Professor Peter Stoett worked to create a new opportunity to work together on TEC, environmental security and sustainable development. He secured funding from the Canadian Institute for Advanced Research for us to engage in critical discourse about the socio-environmental causes and consequences of TEC. We convened in January in Toronto. The diversity of our experience and expertise, our host’s hospitality, and strong and bottomless pots of coffee (for this author) enabled wide-ranging and critical conversations. After workshopping through the intersectionality of TEC with bio-security and sustainable development agendas, we capitalized on the unique opportunity to summarize conclusions with a common voice. It was an unprecedented opportunity to commence unraveling key intersectionalities of TEC.

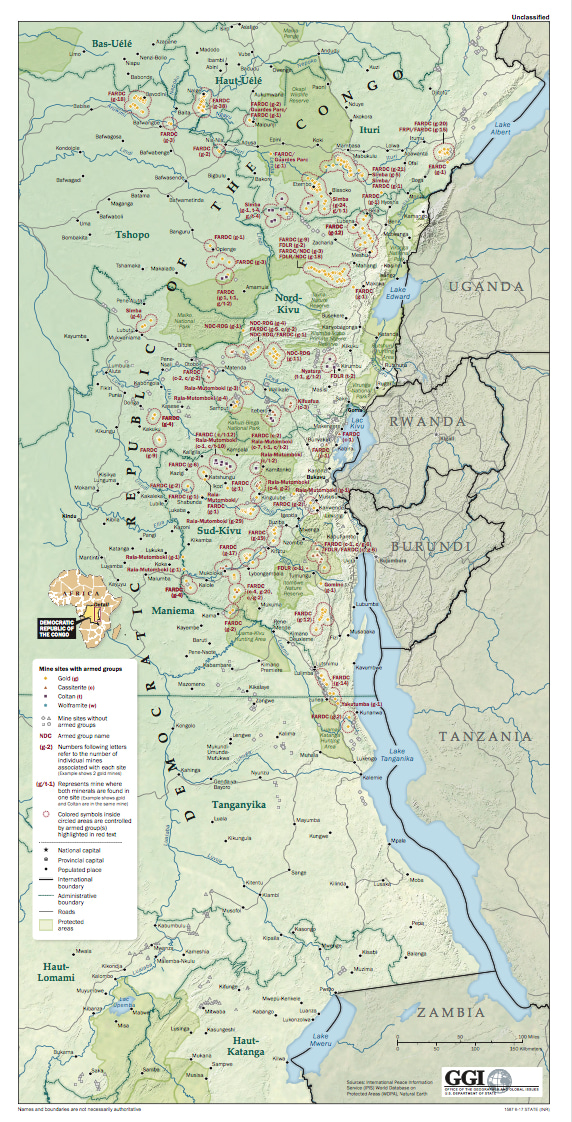

We leveraged our diversity to scope definitions, terminology, and identify strategic opportunities in support of efforts to update sustainable development frameworks. Specifically, we aimed to emphasize the human health and well-being impacts of socio-environmental harms, and delineate the range of knowledge gaps that problematically persist. We posed hard questions such as: can militarized responses that penalize local communities be counter-productive? Are campaigns to educate the public about these crimes too focused on charismatic wildlife species, ignoring criminal activity such as toxic waste dumping or fish crime? How can countries better cooperate to promote bio-security while going after those who benefit the most from environmental crime? What about corporate collusion and government corruption, both major factors in the growth of TEC?

I recall an undeniable urgency to our conversations—which stretched across group dinners and well-bundled walks back and forth between CIFAR and workshop hotel. Transnational environmental crime is not a fringe concern for select corners of civil society but is eroding the roots of human security and community development around the world. Efforts to further the Sustainable Development Agenda and other 2020-2030 planning need to explicitly acknowledge its existence and fight it with strategic, reflective, and humane determination.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Sustainability

This journal publishes significant original research from a broad range of natural, social and engineering fields about sustainability, its policy dimensions and possible solutions.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in