Claiming God’s Land: Spiritual Struggles and Migrant Belonging on Zimbabwe’s Urban Edge

Published in Social Sciences, Sustainability, and Arts & Humanities

The Story Behind the Research

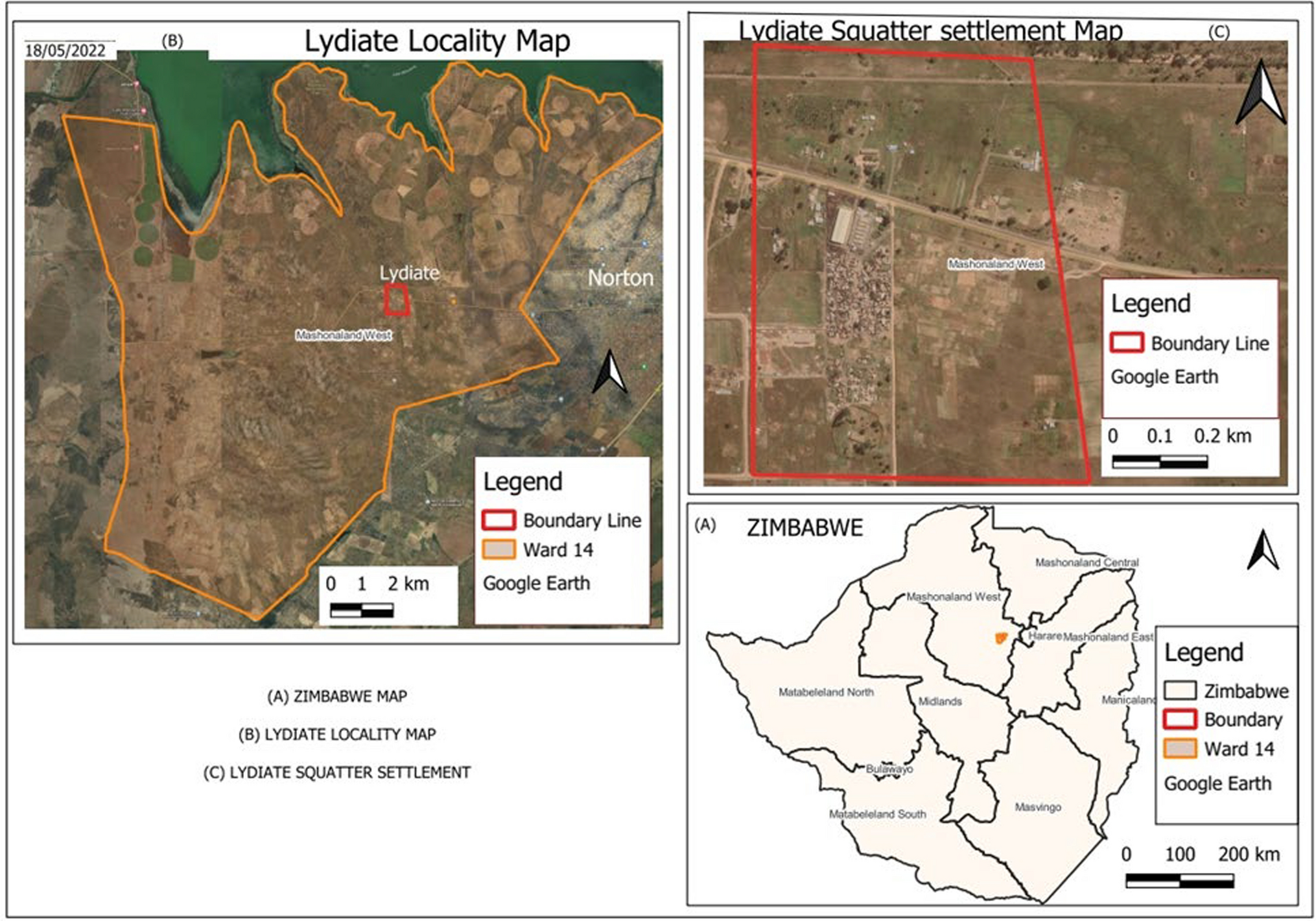

In 2018, I first set foot in Lydiate, a rough peri-urban settlement west of Harare. I had heard whispers of families clearing abandoned plots at night, not out of defiance alone, but because they truly believed the land was a divine gift. As a Zimbabwean who grew up hearing stories of displacement and colonial labour migration, I felt a deep personal pull to understand how these migrants, many descendants of Malawian workers, wrestle space, dignity, and belonging in a city that often ignores them.

My motivation was twofold. Intellectually, I wanted to expand the concept of insurgent citizenship beyond legal battles into the moral and mystical realms that shape everyday life on the urban fringe. Emotionally, I was driven by the resilience I witnessed: grandmothers tending maize under twilight skies, spirits invoked to guard their plots, and neighbours standing as witnesses when disputes erupted. These moments demanded a narrative that honoured both the material and spiritual dimensions of land struggle.

Listening to Voices from the Margins

Over eighteen months, I sat with fifty Lydiatians across generations, farmers in their seventies, young women sowing seeds by the railway buffers, community leaders navigating local politics. I learned that land is not just soil and crops; it is kinship, ritual, and moral economy. Jemtias, an elder, told me, “This land belongs to God! No one should monopolise what the Creator shared.” Petro, a devout Muslim, reminded me of the universal rights of all creatures under Allah.

These conversations revealed a package of tactics: silent night-time seizures of under-utilised plots; communal endorsements by fictive kin; simultaneous claims on multiple parcels as a hedge against eviction; and even the haunting rhythms of Nyau ritual dancers emerging from nearby graveyards to ward off would-be trespassers. Each practice was a voice saying, “We belong here,” in ways that official titles never could.

Theoretical Lenses and Conceptual Innovations

Traditional urban theory often ties citizenship to formal rights and bureaucratic recognition. What I discovered in Lydiate is a richer, more complex claim-making process. Drawing on Holston’s insurgent citizenship, I argue that land seizures become moral-spatial assertions: migrants are not merely breaking rules, they are reframing land as a divine commons.

Bringing moral economies and spirituality to the foreground, this study extends insurgent citizenship into mystical terrain. Rituals like Nyau performances and the strategic invocation of witchcraft deterrence are not fringe phenomena but central tactics for asserting belonging. They remind us that urban struggles in many African contexts are as much about cosmology and moral order as they are about policy and law.

Challenges in the Field

Ethical dilemmas surfaced daily. I navigated the fine line between documenting occult practices and not sensationalizing them. Some migrants feared retribution if their belief in witchcraft became public. Politically, the settlement existed in a grey zone: local authorities turned a blind eye to farming on buffer zones but cracked down on more visible land grabs.

Emotionally, listening to stories of threat, from Chinese investors fencing lands they used to farm to neighbours wielding spells, was taxing. I had to confront my own scepticism about witchcraft while bearing witness to how deeply these beliefs shaped people’s lives. Ensuring anonymity, gaining trust, and respecting sacred rituals required constant reflection on my role as both observer and confidant.

Key Findings

- Self-Allocation as Survival: Migrants clear unused land, roadside strips, commons, abandoned war-veteran farms, to feed their families, believing they have no other options.

- Divine Justification: The refrain “This is God’s land” transforms personal necessity into moral entitlement, challenging exclusive property regimes.

- Communal Safeguards: Consistent use, multiple claims, and endorsements by neighbours create a network of informal tenure security.

- Spiritual Deterrence: Nyau cult processions and witchcraft threats act as powerful deterrents against eviction, no permit needed when fear of the occult stands guard.

These findings show that land access is not just about digging soil; it’s about digging deep into shared beliefs, alliances, and moral claims.

Why It Matters

Urban agriculture is lauded for food security, yet policies rarely account for how vulnerable groups actually get land. Recognising informal access systems, tempered by moral and spiritual dimensions, can guide planners towards more inclusive, flexible governance.

When policymakers see land as more than a commodity, they can legitimise vernacular practices through participatory planning that respects spirituality and migrant livelihoods. This approach strengthens social justice, enhances food resilience, and fosters urban environments where no group is labelled a perpetual outsider.

Reflections and Hopes

I hope readers come away with a new lens: one that sees the spiritual pulse of urban margins, not as a relic, but as a living strategy for survival and dignity. For the general public, this means recognising that permaculture thrives not only through plots and policies but through rituals, communal bonds, and moral energies.

For policymakers, the message is clear: integrate adverse possession frameworks and community-led mapping to formalise what is already working on the ground. For activists and students, let this research be an invitation to listen, truly listen, to unheard voices whose dreams of home and belonging challenge dominant urban scripts.

A Note to Fellow Researchers

Working in politicised, emotionally charged contexts demands humility and reflexivity. Build long-term relationships, respect cosmological beliefs, and engage ethics beyond paperwork: ask who benefits, who is at risk, and how your presence reshapes local power dynamics. Collaborate with community leaders, co-produce knowledge, and be prepared for surprises that defy academic neatness. Above all, carry empathy as your compass.

Follow the Topic

-

Discover Global Society

This is an interdisciplinary, international journal that welcomes research on the complexities of modern global society, its development and its challenges.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Social Policy and Indigenous Rights: Reclaiming Sovereignty, Identity and Social Justice

Indigenous communities worldwide have long faced systemic injustices, including land dispossession, cultural suppression, and socio-economic marginalization. Social policies play a critical role in addressing these historical wrongs and advancing Indigenous self-determination This special issue explores how reparative justice, decolonizing practices, and progressive policy frameworks can contribute to reclaiming Indigenous sovereignty, preserving cultural identity, land rights and ensuring justice for Indigenous peoples. The relationship between sovereignty, identity and justice is central to Indigenous worldviews, yet colonial legacies continue to undermine Indigenous sovereignty. Effective social policies must go beyond symbolic recognition to enact substantive changes that empower Indigenous communities. This issue highlights theoretical research, empirical perspectives, case studies, policy analyses from Indigenous perspectives that examine how legal frameworks, governance reforms and community-led initiatives contribute to sustainable, equitable futures. By fostering a dialogue on Indigenous rights, social welfare policies, this collection aims to illuminate pathways toward justice, resilience and self-determined development for Indigenous peoples worldwide.

Keywords:Indigenous Rights; Social Policy; Land Reclamation; Reparative Justice; Decolonization; Self-Determination; Cultural Preservation; Equity and Inclusion; Indigenous Governance

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Gender, Environment, and Sustainability: Bridging Gaps and Building Future

The pressing challenges of environmental degradation and climate change demand innovative solutions that are sustainable, inclusive, and equitable. Gender, as a critical dimension of social structure, shapes the vulnerabilities, experiences, and responses of communities worldwide facing environmental risks. Women play diverse and pivotal roles as leaders, decision-makers, resource managers, activists, and scientists in addressing ecological issues; yet, they continue to face barriers to access, participation, and recognition within environmental sectors.

This collection, "Gender, Environment, and Sustainability: Bridging Gaps and Building Future," explores the intersection of gender and the environment as a transformative lens for achieving sustainability and social justice. The collection welcomes contributions that examine how gender-based disparities influence environmental outcomes, how women’s empowerment enhances ecological stewardship, and how Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) can be advanced through gender-inclusive policies and practices. Submissions may cover topics such as gendered impacts of climate change, women’s leadership in environmental governance, gender mainstreaming in sustainability science, and case studies from diverse social, cultural, and geographical contexts.

By bringing together global perspectives, empirical analyses, and practical frameworks, this topical collection aims to foster rigorous research and constructive dialogue on the shared journey toward a more sustainable and equitable future for both genders. Researchers, practitioners, and policymakers from diverse backgrounds are invited to contribute their insights and innovations to bridge the gaps and build resilient pathways for future generations.

Keywords:Climate Action, Women’s Empowerment, Gender Equality, Reduced Inequalities, Environmental Sustainability, Quality Education

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Aug 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in