Counting good deeds: a quantitative framework for the evolution of morality

Published in Social Sciences

What constitutes good behavior? How do we best form an opinion about others in our community, and how do we interact with them based on this opinion? The field of indirect reciprocity takes an evolutionary viewpoint to approach such fundamental moral and sociological questions. It is a game-theoretic framework that explores how people form reputations, and how social norms emerge.

Much of the existing research on indirect reciprocity focuses on examining social norms that can sustain cooperation in a society. Past work identified eight successful norms, called the “leading eight”. Individuals using these norms classify each other as “good” or “bad”. They then decide with whom to cooperate based on these binary labels. These simple moral norms can lead to interesting dynamics. For example, when Alice starts with a good reputation, but then cheats against Bob, other group members may start to deem her as bad. In this way, reputations in a population can change in time, depending on how individuals behave and which norms they apply. The leading eight norms have the property that if they are adopted by everyone, the population tends to achieve full cooperation, and defectors cannot invade. Much of this previous work, however, assumes that all relevant information is public. As a result, opinions are perfectly synchronized – if one individual deems another population member as good, everyone else agrees. Yet, in many real-world scenarios, individuals only have access to imperfect and incomplete information. Moreover, individuals can make mistakes when assessing each other’s past actions and don’t share information with one another. When I started with my PhD five years ago, we quickly realized that none of the leading-eight are able to sustain cooperation once information is private and noisy. It became clear that for social norms to be successful under more realistic conditions, a somewhat different approach is needed.

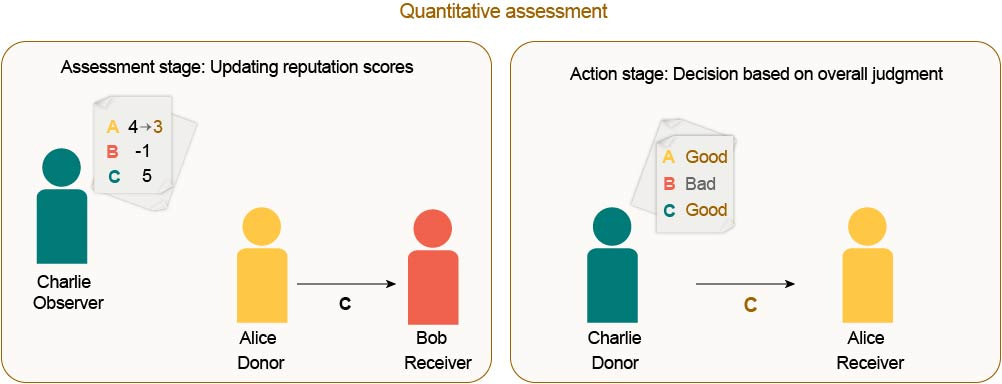

With this negative result as a starting point, I wanted to explore just how reputation systems can circumvent this problem of accumulating disagreements. Together with my collaborators, Christian and Krish, I approached this problem from different angles. For one line of work, I considered a mathematical framework that connects indirect and direct reciprocity (i.e. cooperation based on own personal experience). This work showcases a certain stochastic strategy of indirect reciprocity with an analogue in direct reciprocity. The idea of that strategy is simple; people always deserve a good reputation when they do good things; but even when they do bad things, a society should sometimes forgive. However, in the course of writing my thesis and finishing up my degree, I was still interested in how more complex social norms like the leading eight can be robust when information is imperfect. With this aim in mind, we eventually focused on more realistic assessment mechanics. In particular, we studied the dynamics of complex social norms when reputations go beyond the binary attributes of “good” and “bad”. Instead, individuals represent each other’s reputations by small-range integer scores. For example, Alice may have a score of 5, whereas Bob is a 3. These scores can again change in time, depending on an individuals’ interactions and on the population’s social norms. Reputations below a certain threshold are then overall classified as “bad”, while scores equal to or above the threshold are classified as “good”. This model naturally leads to a more fine-grained and quantitative notion for what it means to be good.

In the course of this study, we quickly saw that such nuanced assessments can dramatically increase the robustness of cooperation. In fact, our extensive simulations showed that quantitative assessments allow four of the leading eight to be stable against defectors and cooperators. Importantly, these four social norms can therefore maintain cooperation even if individuals make their decisions based on imperfect and noisy information. This observation can be formalized. We can prove that when populations adopt one of these four norms, they are more likely to recover from initial disagreements, and this recovery happens more quickly.

Our results demonstrate how sufficiently fine-grained reputation systems can maintain cooperation under conditions when binary black-and-white assessments fail. Surprisingly, however, our findings also suggest that reputation systems should not become overly fine-grained. Instead, there is an optimal scale at which human behavior should be assessed. These findings do not only explain some key features of naturally occurring social norms, but they also have interesting implications for the optimal design of artificial reputation systems. In this way, our study may serve as a starting point for future challenges, by exploring cooperative norms beyond the leading eight.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in