Does ESG rating do its job? No, as a matter of fact, has no correlation with the actual environmental performance of corporations.

Published in Social Sciences, Business & Management, and Economics

In his 2020 annual letter to clients, Larry Fink, CEO of BlackRock, prophesized that a "fundamental reshaping of finance" was about to come because “climate risk” was soon to become “investment risk”. In the same letter he vowed to “measurement and transparency”, and listed some "key actions" to be taken, like publishing a temperature alignment metric for our public equity and bond funds, for any markets with sufficiently reliable data 1 . In the years, several other laudable initiatives followed, including GFANZ, a "global coalition of leading financial institutions committed to accelerating the decarbonization of the economy”, accounting for purportedly 40% of global private financial assets. In a press release dated December 2023 GFANZ pledged for an accurate, transparent, and consistently reported emissions data for real economy companies across Scopes, with the awareness that this will help financial institutions assess climate-related risks 2 .

The two-pronged problem of measurement and transparency in the domain of corporate emissions footprint and, more broadly, of environmental performance, is well known to the Gotha of the financial industry, perhaps even more than to the academics, who for the largest part still ignore, disregard or misinterpret the potential role of the corporate world to pursue sustainability.

Most academics believe, perhaps naively, that the main agency of our society still lies in the domain of public politics. But, as brilliantly stated by the Sheldon Wolin in his book Democracy Incorporated, the present reality is marked by a political moment when corporate power finally sheds its identification as a purely economic phenomenon, confined primarily to a domestic domain of "private enterprise”, and evolves into a globalizing co-partnership with the state: a double transmutation, of corporate and state. The former becomes more political, the latter more market oriented.

Put simply, the goal of sustainability and the quest to achieve a transition to a low carbon economy are unattainable without or against global corporations, because there resides the site of major decisions around our World.

It comes without surprise that politicians are often more aware of this crude fact than academics. The EU is trying to engage (and gauge) corporations effectively towards sustainability, and recently there was great focus on the EU Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive. However, as remarked by Ingka’s Simon Henzell-Thomas (IKEA), ESG disclosure rules “are only useful if they … reduce emissions”, as opposed to being “simply seen as a box-ticking exercise”3.

Evidently, there can't be any accountability or, if you prefer, co-partnership (stewardship?), without measurement and transparency. Thus, the lingering question is, is ESG rating (or the environmental component thereof) transparent, let alone, a good measure of sustainability?

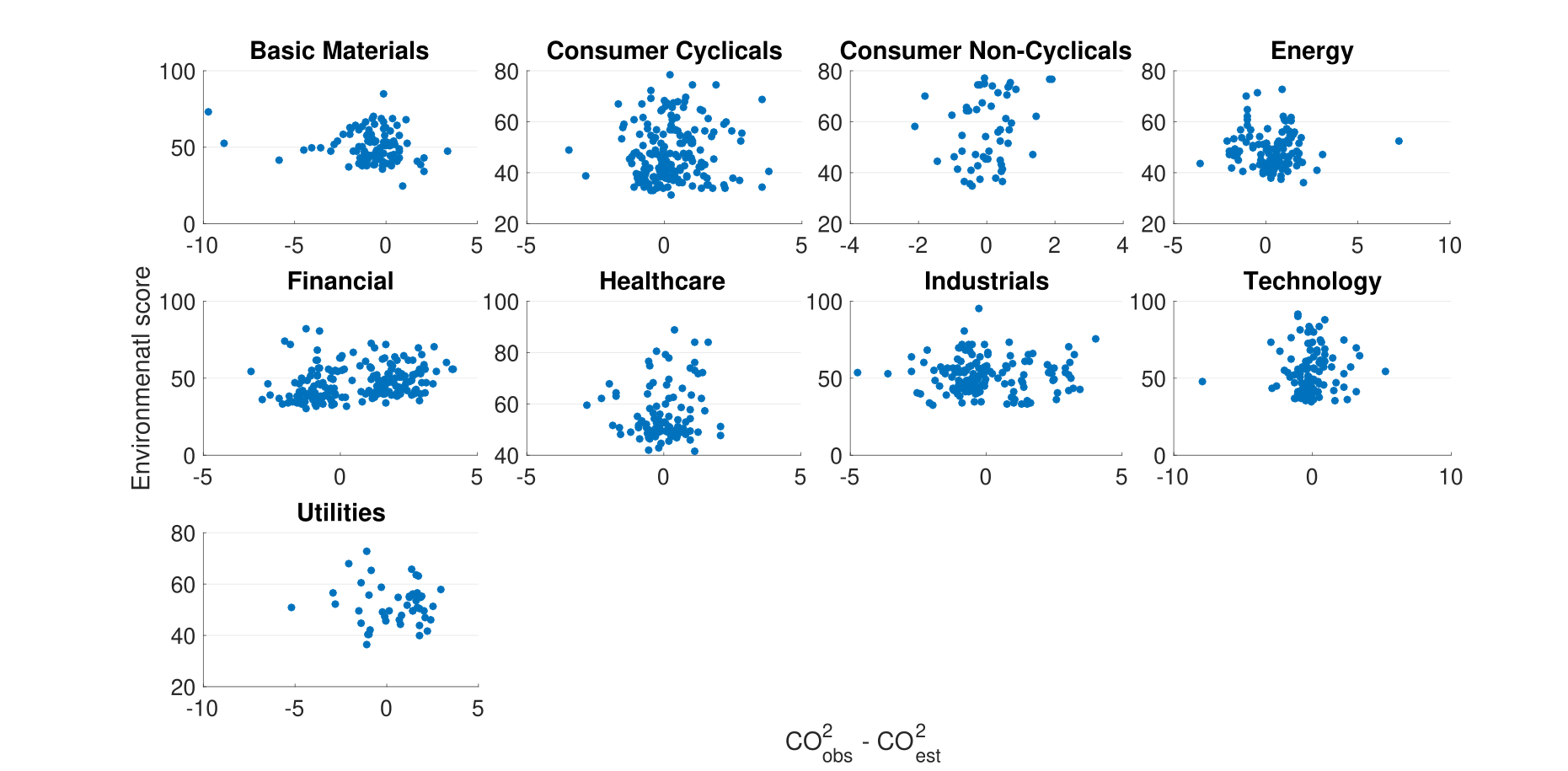

In our study we tested (the environmental score) of one of the most used ESG ratings, that of Sustainalytics and found that it has no correlation with the emissions of global corporations (assessed by size and sector). In the following plot, we compared Sustainalytics ESG ratings and environmental scores for the year 2018 to benchmark deviations of 1104 global corporations for 9 sectors. The Pearson correlation over the whole sample is 0.04, with a p-value of 0.16.

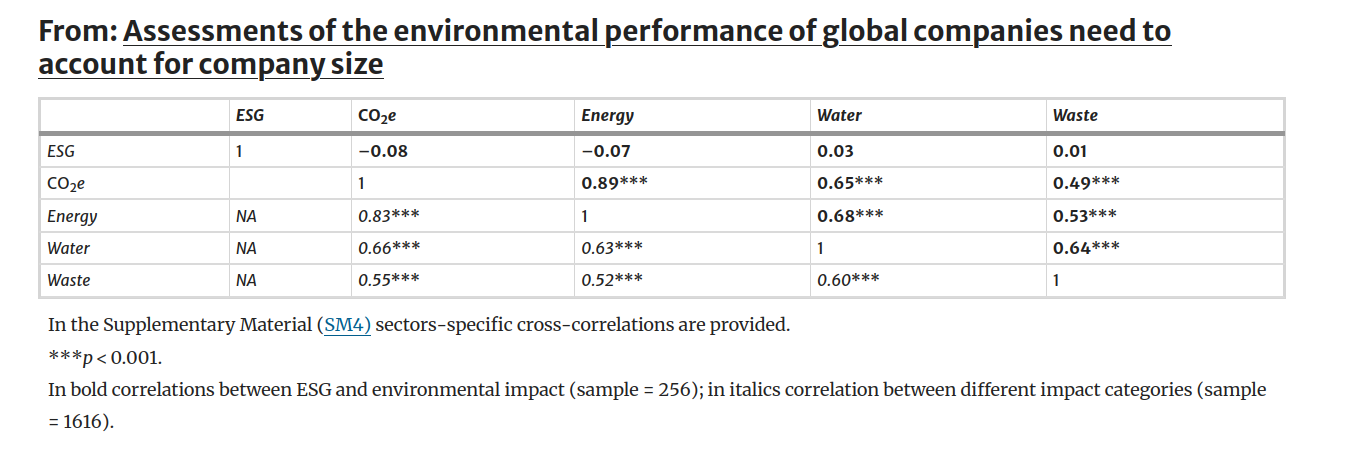

Does the ESG perform better if, instead of corporate emission we consider other environmental impact indicators, such as water withdrawal, waste or energy? Not really. The correlation spans from 0.08 to -0.07.

Experts argue that ESG is a composite and complex indicator that considers, together with emissions/pollution, the broad environmental policy of a corporation. Yet, if complexity reaches the shores of counterfeiting or mystification of the actual environmental impact of an economic activity, what is the use of such metrics for the purpose of guiding (green?) investment, policy scrutiny or public reproach? Does it serve its main purpose of transparency and measurement?

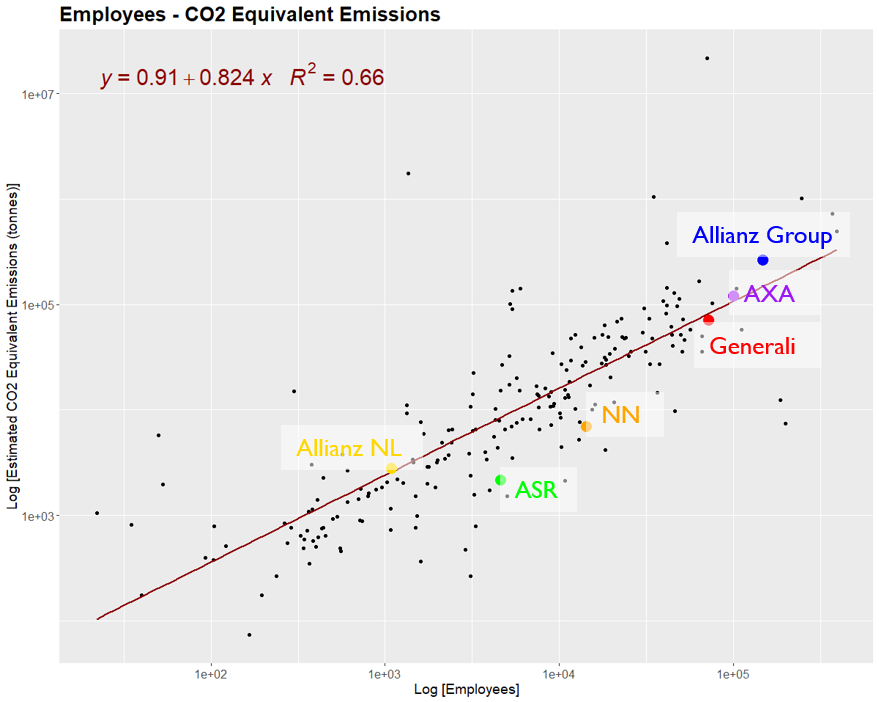

Perhaps, one additional (and little known) reason why ESG ratings fail to assess the environmental performance of corporations is that corporate metabolism is a scaling phenomenon. Assessing the environmental performance of global companies should account for company size in a nonlinear way.

The environmental impact of companies typically scales sub-linearly with size, measured by revenue. This is to say: the bigger the company, the smaller the environmental footprint. Almost always: sometimes the opposite is true: it depends on the economic sector.

Scaling laws, we suggest, can also be used to draft a simple benchmark to efficiently understand environmental corporate performance. The hereby proposed methodology should rely heavily on a vast and open-access database whereupon companies or regulators can estimate the current, sector specific benchmark. Ultimately that means that the more data is available and accessible, the higher the accuracy and transparency of the assessment. Measurement and transparency, is the way. Corporations should share their data and make them public, rather than convoluted and opaque ratings or indicators crafted by third, private parties.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in