Gravity is driving the most depositional sedimentary processes. Its close companion, buoyancy, is strangely enough almost absent from the scene.

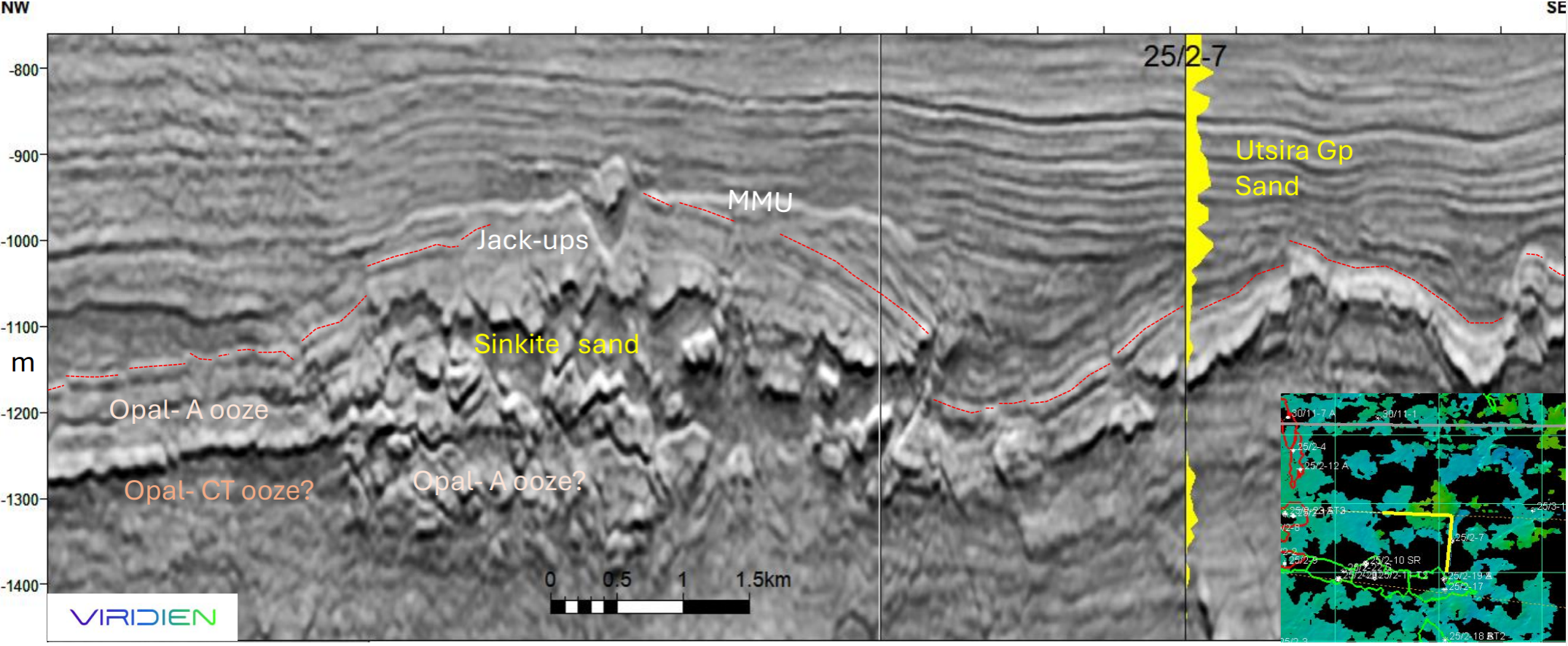

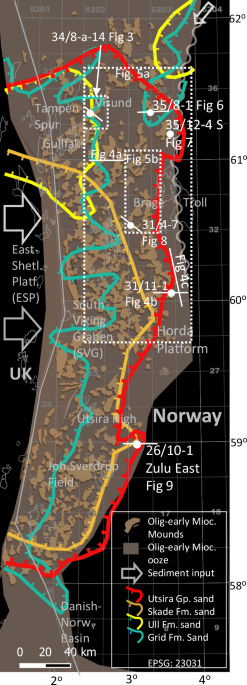

The giant Miocene to Oligocene jack-up structures (mounds) in the Northern North Sea (NNS) (Fig. 1) never had a widely accepted genetic model. They have been explained by combinations of dis-equilibrium differential compaction of in-situ sand and overpressure driven sand injectites sourced from older, hydraulically fractured sand reservoirs. We argue in our paper, Km-scale mounds and sinkites formed by buoyancy driven stratigraphic inversion, based on observations from super-regional, broadband seismic, that their sand core is clearly intrusive but that prior models for sand intrusion can’t explain them.

The conventional injectite hypothesis is clearly inspired by volcanic intrusions forming jack-ups/saucer-shaped intrusions, wings, dykes, and sills when intruded into sediments. While the rise of magma, heat and magmatic gases cause overpressure and explosive eruptions, the main deeper driving force is the buoyancy of the melted rock, as in halokinesis, the other geologic process moving sediments upwards through younger strata and violating the law of superposition.

The well-established models for volcanic intrusions and sand injections seem to have caused a limited focus on looking for the origin of the sand. Generally, authors frequently seem to accept that the parent sand of their presumed injectite sand can't be identified.

Our study initially aimed at evaluating the potential for the large Miocene mounds forming hydrocarbon reservoirs. The basic requirements were obviously fulfilled with giant structural traps containing reservoir quality sand below a seal of low permeable mud rock, all in a very prolific region above some of Norway’s largest oil and gas fields leaking or spilling hydrocarbon upwards.

Most of the nearly thousand wells penetrating the Oligo-Miocene ooze avoided the large mounds but penetrated, however, enough thinner sand intrusive without encountering strong indications for gas or oil, to judge their prospectivity as generally low. Additionally, few indications of hydrocarbons, as expected on shallow seismic data, made us relinquish the area, but with a new genetic model able to explain the likely cause of failure.

We noted the extremely low density, and the consolidated, yet weak and fractured, nature of the opal-A rich bio-silica ooze which are hosting the mounds. The mounds are constrained to this 200-to-500-meter-thick layer and are often eroded, both indicating they formed at seabed and that the large glacial wedges above were not involved. Regionally we observed unconsolidated sand directly above or adjacent to the mounds, apparently connected to the lower sand by sand filled fractures, while potential parent sand in many cases is not present below.

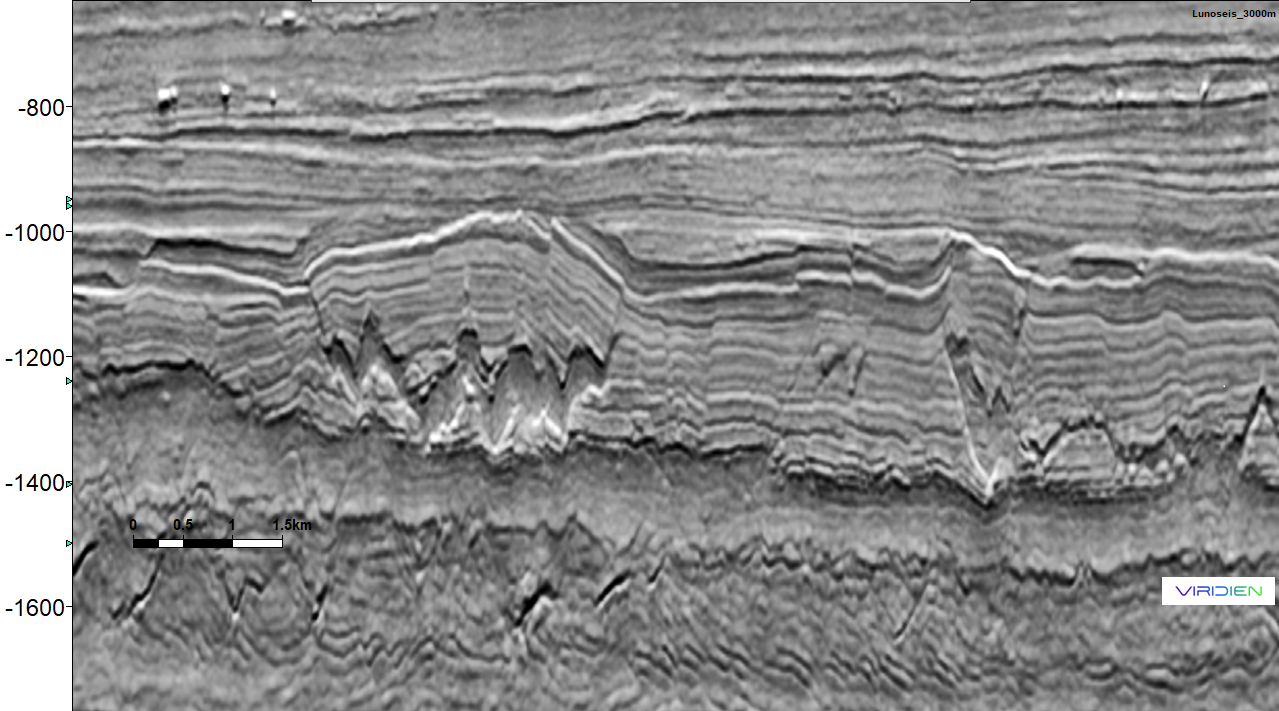

Displaying the regional, high-quality, broadband CGG18 psdm 3D seismic (Viridien) as a blend of relative acoustic impedance and reflectivity (Lunoseis) (Fig. 2), in grey colors, instead of the conventional color displays, was the single factor that contributed the most in realizing the new model. It makes it easier to distinguish the irregular bodies of sand from blocks of consolidated, layered, and low impedance ooze. This becomes even clearer when overlying, in transparent yellow color, the sand intrusive volume extracted from the same seismic data using machine learning (supervised image segmentation) by Earth Science Analytics. The displays often give an intuitive impression of the ooze blocks floating in sand.

In the paper we argue that the mounds are caused by density inversion of unconsolidated sand near seabed, becoming a pseudo-fluid (quick-sand) when liquefied by earthquakes or water expulsion and sinking down fractures in lower density consolidated bio-siliceous ooze which floats up due to buoyancy (Fig.2-7).

Having acknowledged density inversion as a potential mechanism we investigated wells and found mineralogical, petrological and biostratigraphic evidence suggesting an overburden source of the sand intrusive although the sands usually are devoid of in-situ biostratigraphic material and mineralogical/petrographical characteristics to aid correlation.

While acknowledged for at least 50 years as the most likely cause of smaller-scale soft sediment deformation (load casts, ball-and-pillow structures etc) related to earthquakes, density inversion as a process at this scale is, to our knowledge, not yet described within sedimentology. One exception may be the ooze evacuation craters at the same stratigraphic level, and of comparable scales, in the Norwegian Sea, where one paper (Riis et al, 2006), while relying on gravity slides as the primary mechanism for excavating the ooze, suggests it reached its current location several hundred meters up in Pleistocene sediments due to density inversion.

Whether stratigraphic inversion due to buoyancy is a new primary sedimentary process, or a re-mobilization process may be a matter of discussion. We suggested that the sand bodies represent a not yet described type of sedimentary deposit or facies and proposed calling them sinkites to reflect their origin. The ooze rafts (floatites) are allochthonous blocks of ooze with their internal millions of years of stratigraphy intact and clearly re-mobilized, except in cases where very soft ooze may have been displaced or dug out by and mixed with sand and thus forming a new sediment (see early part of the reconstruction video in Fig. 4).

Sinking sand is fracturing the otherwise tight bio-siliceous mud-rock (ooze) and the trap potential for hydrocarbons and CO2 in the mounds seems restricted by the trapping potential of the remaining overburden sand and the amount of sand in dykes and sills in the ooze within the closure, like in the 26/10-1 Zulu East gas discovery NE of the Johan Sverdrup Field (Rudjord et al. 2024). A few wells have, however, presumably indications of hydrocarbons in shallow mounds suggesting that sinkites can be sealed by e.g. completely removed/sinked-in parent sand. In the article we are not evaluating morphologically similar structures, which are well established to be caused by upwards injected sand, in deeper and more prospective Paleogene strata.

Turning existing models up-side-down by bringing a potential new, large-scale geological process to the table is not, and perhaps shouldn’t be, easy. When almost stumbling into the new model 4-5 years ago, after much effort trying to understand the mounds based on existing models, I felt the new model so intuitive and solving so many controversies that I was almost afraid of losing control by presenting it. However, only very few colleagues embraced the idea and saw the potential of considering a nearly untested mechanism to explain these enigmatic features. Among those were my co-authors in the extended abstract for EAGE in Oslo in 2024 (Sinkites, More than a Theory? Observations from a Miocene Gas Discovery, East of the Sverdrup Field), some of whom invented the name ‘sinkite’ 10 years ago for the features but never formulated a model, and Steve Thomas who I managed to convince with my first written draft paper and who later strongly supported me in improving the material. In most cases it was received with disbelief, polite interest, friendly jokes or active resistance, but not, in my opinion, with strong scientific arguments against the hypothesis. Anyway, and fortunately, Aker BP saw the importance of allowing differing scientific views and supported publishing our hypothesis in a high impact journal although they thereafter decided not to support further promotions of the theory to avoid being seen as a part in a scientific debate.

Expert domains are narrowing as our total knowledge increases, and it becomes ever more important to widen our perspectives to avoid ending up in rabbit-holes. Buoyancy is difficult to understand, but also intuitive and in my experience easier to accept as a genetic model for the mounds by generalists and by non-geoscientists. Becoming an “expert” myself, I see, however, my own tendency to explain features as sinkites when other options may be equally plausible.

It was reassuring, then, to realize the open attitude of some of the major experts and founders of modern injectite theory encouraging us to look outside conventional models to explain the 100-200-meter-thick sand, and in particular my co-author Mads Huuse who saw the potential early on and became ever more enthusiastic as we worked through the observations and formulated the model together.

We are grateful for the thorough review by Communications Earth & Environment. The reviewers’ very positive feedback encouraged us to improve the paper by accommodating their considerable list of requirements and potential improvements. It is, however, noteworthy that none of them, and no other we know of, have identified any flaws in, or major obstacles to our hypothesis, and only pointed at alternative models and perceived weaknesses in some of our arguments. The main objection seems to remain “it’s not possible”. An understandable emotional and potentially valid objection, but not one that should be given scientific weight unless supported by written and accessible argumentation.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in