Dynamical systems show the flexibility of neural connectivity

Published in Neuroscience, Protocols & Methods, and Mathematical & Computational Engineering Applications

What was meant to be a pit stop on the way to large-scale brain dynamics models turned into a whole new road trip into the world of C. elegans research. When our team first posted our decomposed linear dynamical systems (dLDS) model on arXiv in May 2022, we wanted to explore how we could leverage our new modeling framework to describe overlapping processes in time and space in a real nervous system. We decided to start with the most thoroughly studied nervous system, C. elegans, and began by testing dLDS on a now-classic C. elegans dataset, Kato et al., 2015. While our initial exploration confirmed that we could indeed provide a finer-grained account of neural dynamics motifs that corresponded to different behavior states, the dataset clearly had a lot more to offer through the lens of our analysis, so we started digging deeper.

As we analyzed each worm, its dLDS model components, and each neuron over time, we were able to appreciate the rich heterogeneity in C. elegans neural activity and behavior that were often ironed out by averaging-based analyses. We reached out to colleagues in C. elegans neuroscience who helped us contextualize our findings. Through these conversations we learned just how much of a knowledge gap remains between the map of synaptic connections between C. elegans neurons and even the one-to-one signal propagation relationships between them, let alone multineuron, nonlinear, and GPCR-mediated long-range relationships. We found evidence to support the following perspective shifts:

- Habituation can be qualitative and quick - a sensory neuron’s connectivity can shift rapidly to new combinations of neurons over the course of minutes.

- An interneuron’s function can be difficult to define. We propose that an interneuron’s function should not only be defined by when and how much it fires, but also how its nervous system-wide instantaneous dynamic connectivity patterns change (i.e., connectivity tuning vs. activity tuning).

- Even behavioral states that look similar and discrete are generated by diverse and continuous internal neural states.

- It is important not to underestimate individuality. Even an organism with a small nervous system can execute the same behavior in different ways.

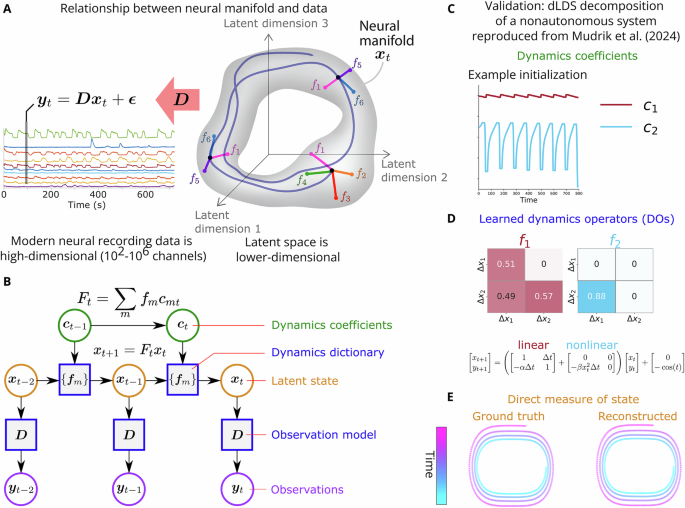

dLDS and its extension in our new paper give scientists a few tools to work with when analyzing brain recordings from one individual or across individuals. Dynamical systems models look for relationships between dimensions over time. This is a different perspective on correlation than more traditional functional connectivity identified through, e.g., PCA; we’re not just looking at what fires together at the same time, but what’s consistently active in sequence. In our case, we first map to a lower-dimensional space to make this analysis more tractable and interpretable. Each dLDS model returns a 1) mapping from the recording space (e.g., neurons) to a lower-dimensional latent space; 2) a set of latent states that describe how the lower-dimensional version of the neural data evolves over time; 3) a set of matrices that describe the dynamics (dynamics operators); and 4) a set of coefficients that describe which dynamics operators are active at each time point. By learning this model description, we can then describe instantaneous dynamic connectivity by summing the dynamics operators together at a given time point, weighted by their time-dependent coefficients, and then map those back to the higher-dimensional space to see which neurons they modulate.

Throughout this process we grappled with a number of challenges. One was visualizing dynamic connectivity in the neural space without overwhelming the reader. We chose to show only the smallest top percentage of strongest connections and focus on connectivity over anatomical location, but we recognize that a rich connectivity structure lies beneath that. Another was comparing dynamics and coefficients between per-worm and aligned dynamics models. We found a great degree of overlap in both, and an interesting direction of future work is to dive deeper into what these overlaps mean in terms of cross-worm behavioral similarities.

While we focused our analysis on grounding our C. elegans dynamic connectivity findings in the known behavior and environmental variables, this process opened up new questions about how dLDS can shift our perspectives on other nervous systems, too. Working with larger organisms brings new challenges, e.g., with respect to preprocessing and hyperparameter tuning, but larger nervous systems also contain rich representations that we conceptualize as internal cognitive states, neither purely motor nor purely sensory. Using future versions of dLDS, we hope to learn more about what distinguishes the dynamic connectivity that accounts for these internal states, which can be spread across the brain, defying traditional definitions of brain regions and functions, and which can change over time as brains adapt and learn.

We thank you for reading our paper and we hope that it will change the way you think about what connectivity and neural states mean. We also hope that the C. elegans nervous system will inspire you with its ability to adapt to, and perhaps learn from, its environment at any given moment. We can’t stop marveling at what it can do with only 302 neurons!

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in