Fluorescent Surprises in Protein Cleavage

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology, Chemistry, and Cell & Molecular Biology

Fluorescence has become one of the most versatile tools in modern science. From tracing how neurons communicate in the brain to detecting the spread of viruses in a cell, fluorescent proteins act as molecular lanterns that illuminate processes invisible to the naked eye. The discovery of green fluorescent protein, or GFP, from the jellyfish Aequorea victoria in the 1960s transformed biological research. GFP, with its small chemical unit, known as a chromophore, absorbs light and re-emits it as a green glow. When researchers learned how to attach GFP to other proteins, it became possible to watch biological processes unfold inside living cells. This heralded an era where GFP and other fluorescent proteins reshaped fields as diverse as medicine, genetics, and materials science.

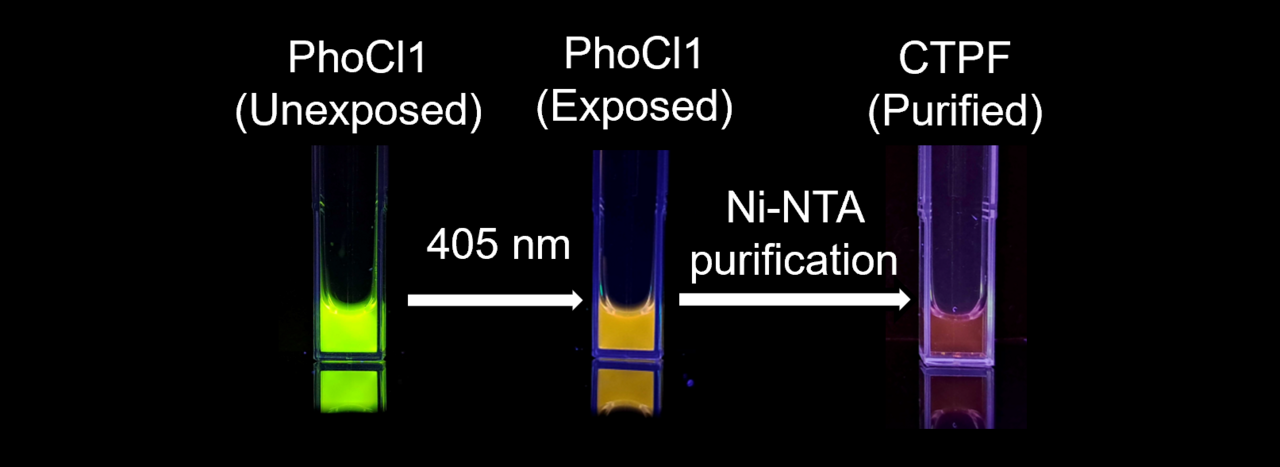

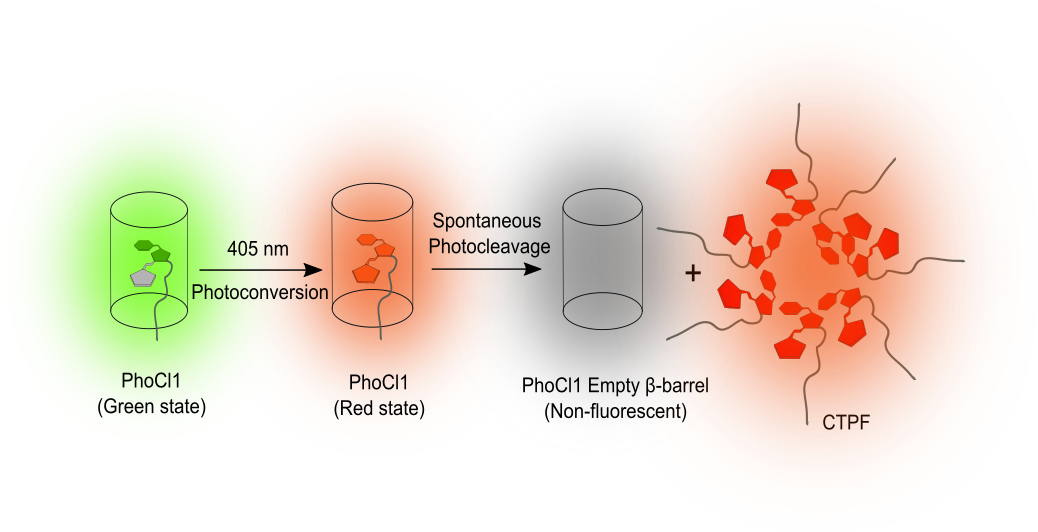

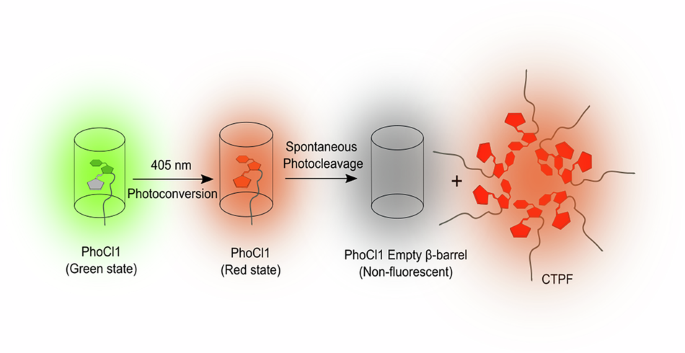

Yet, even within this well-explored field, nature continues to hold surprises. We have reported an unexpected property in a protein known as PhoCl1. Originally developed as a light-sensitive biological switch, PhoCl1, when exposed to violet light, undergoes a process called photocleavage. This process splits the protein into two parts, the larger empty β-barrel and the smaller C-terminal peptide fragment (CTPF) that carries the chromophore. Until recently, it was believed that once this break occurred, the fluorescence was lost. However, our study, published in Communications Biology, has now shown that the small fragment of the photocleaved PhoCl1 produces an unexpected dim red glow.

Discovery through the LAMP Technique

The finding emerged from our development of light-assisted molecular purification (LAMP), an in-house developed method for purifying proteins.1 In this method, we used PhoCl1 as a removable tag fused to a protein of interest or the target protein. When illuminated with violet light, PhoCl1 cleaves, leaving the empty barrel behind on the purification beads and releasing the protein of interest into solution. Released along with the protein of interest was a short tail of nine amino acids, which constitutes the CTPF.

During these experiments, we noticed that samples exposed to light emitted a faint red fluorescence. To determine the source of this glow, we performed the process with PhoCl1 alone. The larger β-barrel was non-fluorescent, as expected, but the small CTPF consistently gave off red light. This observation shifted the study’s focus to the investigation of the unusual behaviour of this fragment.

Following the faint signal

Having established that the glow came from the fragment itself, we looked for the underlying mechanism. Intact fluorescent proteins contain the chromophore, which is nestled inside a protective β-barrel structure that prevents water contact and maintains structural rigidity necessary for efficient fluorescence. We observed that the CTPF does not exist as isolated fragments in solution but tends to form aggregates. When multiple CTPF fragments aggregate, they mimic the protective environment of the β-barrel by pushing away water from their local surroundings, forming hydrophobic pockets. Within such clusters, the chromophores are once again shielded from water and their movements are restricted, allowing them to emit light, though with lower intensity.

We confirmed this aggregation mechanism through dynamic light scattering experiments that detected particle aggregation. Complementary molecular dynamics and quantum mechanics/molecular mechanics simulations revealed that aggregation induces structural rearrangements in the chromophore, reducing its exposure to water and stabilizing conformations favorable to fluorescence.

Physicochemical Sensitivity and Rethinking Photocleavable Fragments

We further tested how the emission responded to changes in the environment, and found that variations in temperature, salt concentration, and acidity altered the fluorescence intensity. These findings confirmed that the fluorescence depends not only on aggregation but also on external conditions. Moreover, our study challenges the conventional assumption that photocleavable proteins generate biologically inactive or inert fragments after cleavage. The persistence of CTPF and its intrinsic fluorescence upon aggregation calls for a reassessment of how photocleaved fragments are considered in experimental design and data interpretation involving light-sensitive proteins. By uncovering new properties of photocleavable proteins, we suggest potential avenues for the development of light-activated fluorescence systems, AIE-based biosensors, and tunable biomaterials for protein tagging and responsive material design.

Reference:

- “Light-Activated Molecular Purification (LAMP) of Recombinant Proteins.” Bioconjugate Chemistry 35, no. 9 (September 2, 2024): 1343–51. https://doi.org/10.1021/acs.bioconjchem.4c00284.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in