From pocket lizards to mighty dragons: evolution of growth patterns in monitor lizards

Published in Ecology & Evolution

Babies and adults of most animals are very different from each other. For starters, babies are usually much smaller and this impacts how they interact with the world. Think of baby leatherback sea turtles. As we have learned from tearful nights watching nature documentaries, those poor souls are the favourite snack of every animal on the beach. However, adult leatherbacks are formidable hunters of soft-bodied animals and have few natural predators. Babies and adults of the same species may also show wildly different body types that reflect how the individuals in each of these life stages interact with their environment. In a very dramatic example, the morphology of caterpillars and butterflies has evolved to efficiently solve their most pressing priorities: eating for one, breeding for the other.

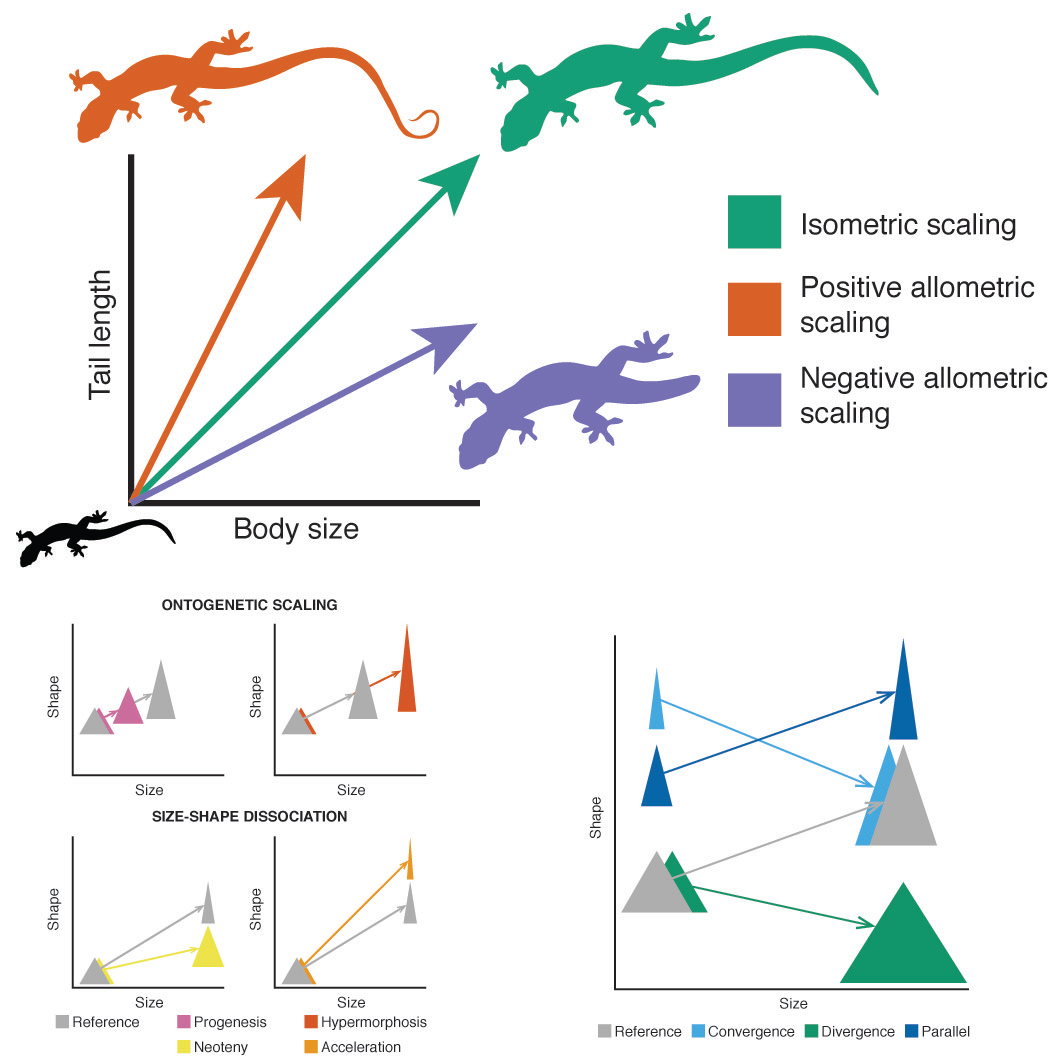

These examples illustrate how growth and development (ontogeny) can have a large impact on the biology of organisms. It then comes as no surprise that ontogeny captured the attention of many influential evolutionary biologists. These scientists laid out a conceptual framework that is still used today. We can think of ontogenetic changes in morphology as trajectories in a two-dimensional space, where we have body size (commonly used as a representation of age) in the x-axis and another trait (e.g., head size) in the y-axis. The size of traits can scale either proportionally (isometry) or not (allometry) with respect to body size. For example, humans show allometric growth because babies have heads that are larger in relation to their bodies than those of adults. Allometry is common in nature because if body parts scaled proportionally to size they would not be as efficient biomechanically. For example, the long and slender legs of juvenile t-rexes were built for speed. The legs of adult t-rexes were proportionally shorter and more robust, or they would collapse under the massive weight. Thus, changes in body size impose limits on the variation of other traits.

Evolutionarily speaking, ontogenetic allometric trajectories can differ between species in several ways. Changes in the intercept produce parallel trajectories. Changes in direction can result in ontogenetic convergence or divergence. In the former, adults of different species are more similar to each other than juveniles, while in the latter it’s juveniles that are alike. Heterochrony refers to changes in the rate or timing of development. When it happens, some species will end up looking more “adult-like” (peramorphic) with respect to others that are “juvenile-like” (paedomorphic). A classic example is the adult axolotl, an aquatic salamander that resembles the young of other salamander species.

While ontogeny has intrigued scientists for a long time, studies comparing the ontogenetic trajectories of different species are scarce and usually focus on a few species. Part of the reason is that these studies require recording morphological data for many individuals of different ages. This is time-consuming and obtaining good sample sizes can be difficult for species that have rarely been collected for scientific purposes. Furthermore, comparative studies require a good understanding of evolutionary relationships (aka phylogeny), which are unknown in many groups of organisms.

Enter the dragon

When I arrived at Scott Keogh’s lab in the Australian National University to start my PhD, my lab-mate and friend Ian Brennan was working on the phylogeny of monitor lizards (look at the results here). Monitor lizards (genus Varanus) are a fascinating group of reptiles. Most of them are intelligent and active predators, and the group includes the largest terrestrial lizards to have ever existed such as the five-meter extinct Megalania and the three-meter Komodo dragon. However, most of them are in the 1–2 m range and there is a group of small-bodied Australasian monitors, of which the smallest is around 20 cm long. The difference in size between Megalania and the smallest monitor is as large as the difference in height between an average human and a 40 m tall building. These extreme size differences are also observed between juveniles and adults of the same species. If baby humans grew as much as Komodo dragons during their lives, adult humans would weigh about 2.5 metric tons. As a result, the ecology of hatchling and adult monitors can be very different. Juveniles of many species live up in the trees to avoid predators, including adults of their species. As they grow, they can remain arboreal, become terrestrial, or become semi-aquatic, depending on the species. The huge differences in body size between and within species, ontogenetic changes in ecology, and the fact that we have a reliable phylogeny make monitor lizards an ideal candidate for comparative studies of growth patterns.

There was only one missing ingredient in the recipe for this study. Exactly! I needed morphological data. As much as I like observing lizards in the wild, I didn’t have the time to travel around the globe to catch hatchlings, juveniles, and adults of the around 80 monitor lizard species that have been discovered so far. That’s where natural history collections and museums come in. Their specimen holdings are priceless reservoirs of information for scientists and conservationists (please support your local museums!). So I took my bags and travelled to 11 herpetological collections in five countries. I obtained body and limb measurements, as well as head photographs, of over 1,600 specimens. It was hard work. I could only spend a few days in each museum, so I would work long hours. But it was also a lot of fun. Natural history collections are a playground for nature lovers. Sometimes my partner came along to visit parts of the world that we had only dreamed of as average inhabitants of Mexico City.

What monitor lizards teach us about the evolution of growth patterns

Measuring thousands of lizards was just the beginning. What came after that was months of data processing and analyses. I joined forces with my PhD supervisor and with Damien Esquerré, who previously published a paper on the ontogeny of another group of reptiles containing tiny and huge species: pythons. All this work was worth it when we started seeing the interesting patterns that our data was showing.

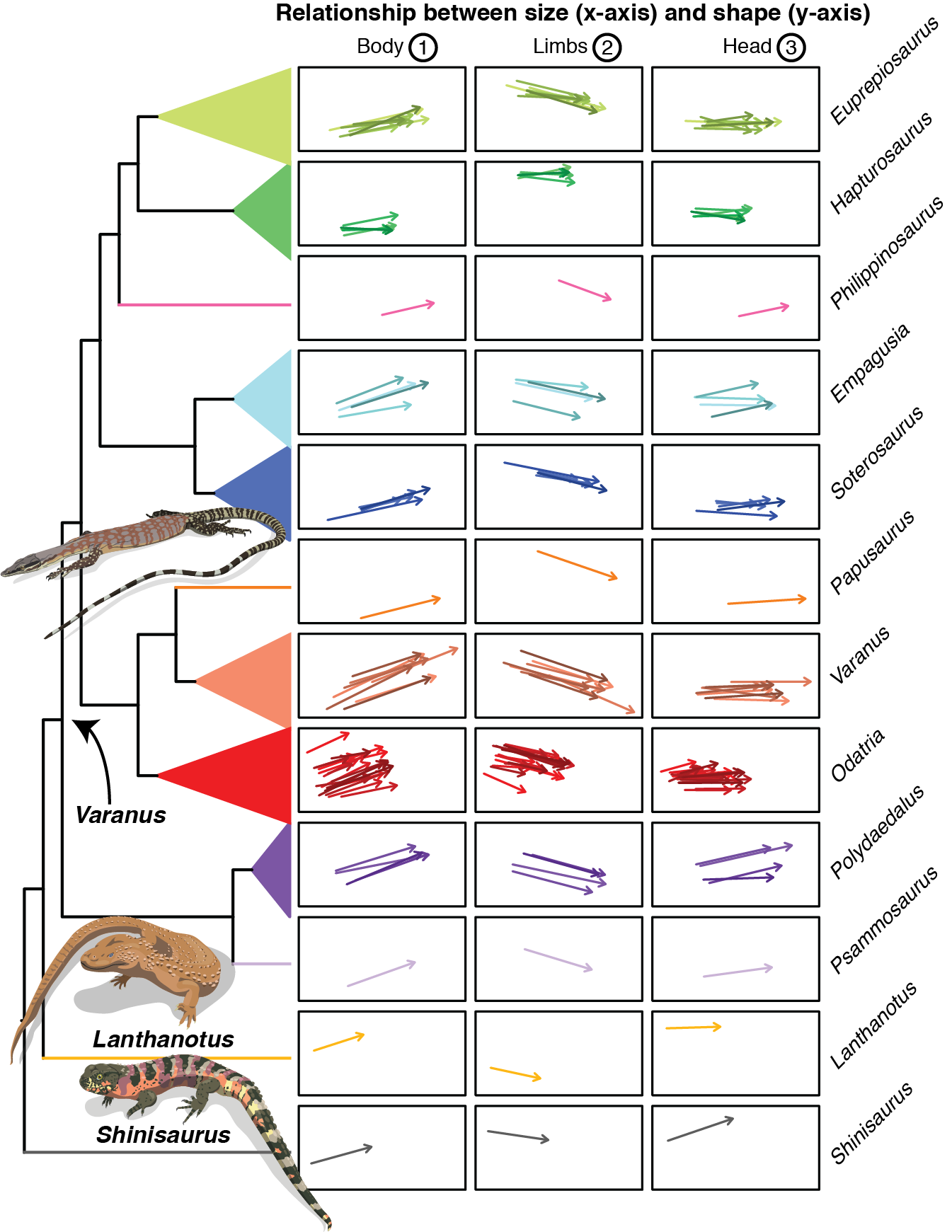

Our analyses showed that there is great diversity in the way that the body, limbs, and head of monitors and closely related lizards change as they grow. The trajectories of Hapturosaurus, a group of highly specialized arboreal monitors, are quite distinct. We found that in many monitor species juveniles have comparatively longer tails, an adaptation for climbing in lizards. Furthermore, we found that in many groups the juveniles of different species are more similar to each other than the adults. This probably reflects the fact that many species climb regularly as juveniles and thus benefit from similar adaptations. As they grow, some species will still climb a lot, but others become terrestrial or semi-aquatic. Thus, from similar starting points, monitors diverge into a variety of shapes.

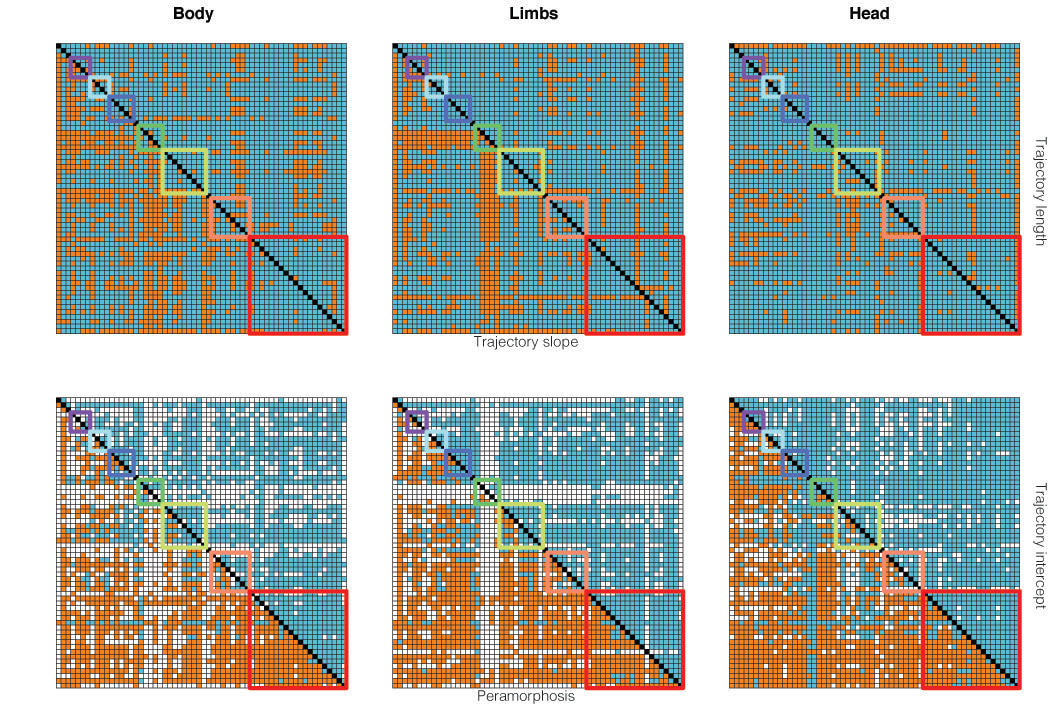

In agreement with previous studies, we found that heterochrony (change in timing/rate of development) is a more common way for species to differentiate than changes in the intercept or direction of the trajectories, which are more evolutionarily conserved. This reveals the evolutionary constraints imposed by allometry, because it indicates that there is a limited number of ways in which the different body parts can respond to changes in body size. We also found that heterochrony is responsible for the characteristic body shape of monitor lizards: they have the body proportions of juveniles of the Borneo earless monitor, their closest relative. The short-tailed pygmy monitor has some of the most adult like proportions amongst monitors. This may seem surprising, because Varanus species are on average much larger than the Borneo earless monitor and the short-tailed pygmy monitor is amongst the smallest monitors. This suggests that there is an evolutionary disconnection between size and shape (see the bottom panel on the first figure for a graphic representation). This is not unheard of: some small frogs have peramorphic skulls and some giant dinosaurs had paedomorphic teeth. Not surprisingly, the Komodo dragon is peramorphic, a “more adult” version of its closest living relative, the lace monitor.

Finally, we used phylogenetic comparative methods, a set of tools used to explicitly incorporate phylogeny into evolutionary research, to characterize the evolution of the trajectories. To our knowledge, this is the first time that ontogenetic allometric trajectories are analyzed in such a way. We found that the magnitude of ontogenetic change is evolutionarily constrained around an optimal value, but it seems like ecological factors such as habitat preferences and competition between species are driving the evolution of the direction of ontogenetic change. We also found that the evolution of the trajectories is particularly slow in a group of large monitors, suggesting that large size may be imposing evolutionary constraints on development, an idea put forward by renowned evolutionary biologist Stephen J. Gould.

Our study shows that a combination of ecological factors and evolutionary constraints imposed by size have shaped the ontogenetic diversity of monitor lizards and their close relatives. Whether the patterns that we observe in this group of reptiles hold true for other kinds of organisms remains to be tested. The generation of reliable phylogenies and comprehensive morphological datasets will be crucial in that quest. Continuing support and funding for research institutes and natural history collections will be necessary to fully uncover the mysteries of growth.

If you enjoyed the read, check out our paper in BMC Ecology and Evolution, it’s open access: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12862-022-01970-6

Follow the Topic

-

BMC Ecology and Evolution

An open access, peer-reviewed journal interested in all aspects of ecological and evolutionary biology.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Bioacoustics and soundscape ecology

BMC Ecology and Evolution welcomes submissions to its new Collection on Bioacoustics and soundscape ecology. By studying how animals use sound and how noise impacts them, you can learn a lot about the well-being of an ecosystem and the animals living there. In support of the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 13: Climate action, 14: Life below water and 15: Life on land, the Collection will consider research on:

The use of sound for communication

The evolution of acoustic signals

The use of bioacoustics for taxonomy and systematics

The use of sound for biodiversity monitoring

The impacts of noise on animal development, behavior, sound production and reception

The effect of anthropogenic noise on the physiology, behavior and ecology of animals

Innovative technologies and methods to collect and analyze acoustic data to study animals and the health of ecosystems

Reviews and commentary articles are welcome following consultation with the Editor

(Jennifer.harman@springernature.com).

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 27, 2026

Ecology of soils

BMC Ecology and Evolution invites researchers to submit their work on soil ecosystems and their implications for environmental sustainability. Soils are living, dynamic systems that support a vast array of organisms, from tiny microbes to plants and animals. They play a vital role in keeping our planet healthy by recycling nutrients, storing carbon, and helping regulate water and climate. Understanding how soil life functions and adapts is essential for tackling major environmental challenges like climate change, habitat loss, and soil degradation.

This collection of articles aims to showcase the latest research in soil ecology, emphasizing the interactions among soil organisms, biogeochemical processes, and ecosystem functions across various landscapes. We invite submissions that explore the following topics:

•Microbial and faunal diversity in soils: Patterns, drivers, and functional roles of bacteria, fungi, protists, and invertebrates

•Soil biogeochemistry and ecosystem functioning: Nutrient cycling, carbon sequestration, and soil health in both natural and managed ecosystems

•Soil-plant interactions: Rhizosphere processes, plant-microbe symbioses, and their effects on vegetation dynamics

•Land use and climate change impacts on soil communities: Responses of soil biodiversity and functions to agricultural intensification, urbanization, pollution, and climate shifts

•Soil metagenomics, phylogenetics, and functional ecology: Advances in molecular approaches for studying soil microbial and faunal communities

•Conservation and restoration of soil ecosystems: Strategies for maintaining soil biodiversity and ecosystem services in degraded landscapes

All manuscripts submitted to BMC Ecology and Evolution, including those submitted to collections and special issues, are assessed in line with our editorial policies and the journal’s peer review process. Reviewers and editors are required to declare competing interests and can be excluded from the peer review process if a competing interest exists.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 15: Life on Land.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Jun 02, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in