How to grow as a scientific communicator

Published in Education and Arts & Humanities

Growing as a scientific communicator

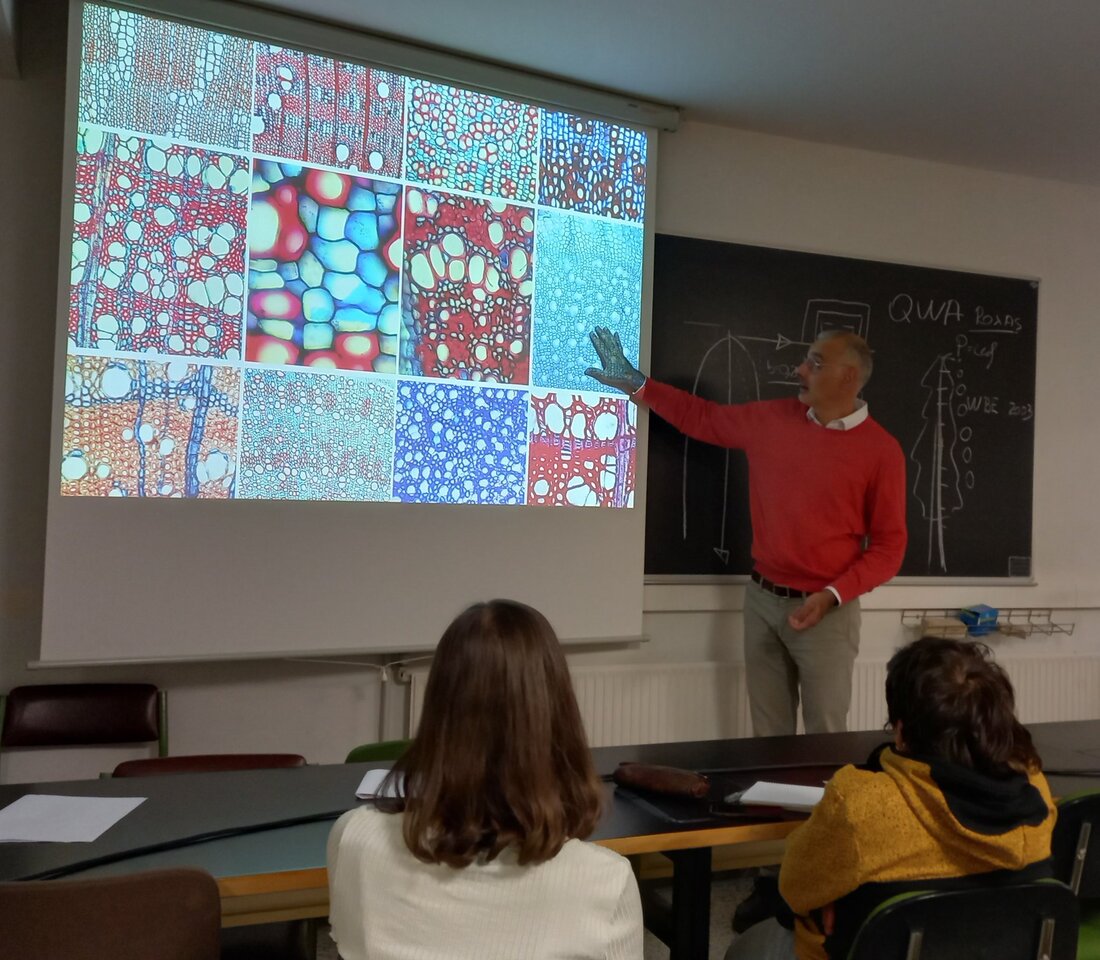

When I teach scientific writing and presentation skills to PhD students, I see the same pattern repeat itself. At first, students are preoccupied with themselves: How will I look? Will I sound professional? Will I seem competent enough? Later, their focus shifts almost entirely to content, including methods, data, and statistics. Only much later do they discover the real key to effective communication, thinking about the audience.

I recognise this progression because I went through it myself. When I wrote my first papers and gave my first scientific presentations, I worried about my image and whether I would be judged harshly or questioned badly. As my confidence grew, I invested energy in my slides, data, and text, ensuring every detail was accurate. Only later did I realise that the real aim is to help the audience understand and connect with our message.

This journey, from self to content to audience, marks the three stages of growth in scientific communication. Learning to guide students through these stages has shown me that the audience-focused phase is not only the most difficult to reach, but also the most transformative.

Stage one: Focusing on ourselves

Every scientist begins in a self-focused phase. Early-career researchers, such as the PhD students I teach, are understandably preoccupied with their reputation and performance. They worry about their accent during a talk, their grammar in a paper, or whether their slides look good enough. I often see them begin presentations by apologising for how nervous they feel or for English not being their native language. Their attention is fixed on how they appear, not on what their audience is taking in. This excess of self-consciousness is normal; however, insecurity often overshadows clarity. The danger is staying too long in this phase, where communication risks becoming more about image than substance.

Stage two: Focusing on the content

As confidence grows, the focus shifts from self to content. Researchers in this stage care deeply about the quality of their data, the rigour of their methodology, and the logic of their arguments. I see this in students who pack their slides with every figure, every table, every result, anxious to show mastery and deep knowledge. The content is strong, but the delivery is often overwhelming, presenting too much information for the audience to absorb. This phase represents progress: the content truly matters. But communication can still fail if it remains disconnected from the audience. A talk that loses its listeners, or a meticulous paper that no one can follow, is not successful communication.

Of course, these stages are not always neatly separated. Many researchers experience phases one and two simultaneously: insecurity about their results often fuels anxiety about how they appear, leading them to overcompensate with formality or excess detail.

Stage three: Focusing on the audience

The real breakthrough comes when we stop asking, “How do I look?” or “Is my content complete?” and start asking, “What does my audience need?”. This is the most challenging but also the most rewarding stage. I can tell when students begin to make this shift. Their slides suddenly contain fewer words, but more clarity. They pause to explain a concept that they once assumed was obvious. They reorganise a paper not according to the chronology of their experiments, but according to the logic that best guides a reader or a listener. This is the moment when communication stops being a performance or a list of findings without context and becomes an act of true knowledge transfer.

At this stage, scientific communication becomes not only clearer but also more powerful. Editors and reviewers are more persuaded, listeners are more engaged and more likely to remember and build on your work.

How to make the shift happen

However, moving toward audience-focused communication is not automatic. The transition to this third stage rarely happens automatically. It takes deliberate practice. Experience helps, but often it takes explicit feedback, mentoring, or moments of self-awareness to realise that clarity and connection matter more than performance. This is why teaching, peer review, and supportive mentors are so important: they accelerate the shift from self or content to audience. So how can early-career researchers accelerate this shift? In my teaching, a few practices are particularly effective. Before writing or speaking, I encourage students to pause and ask themselves three questions: Who is my audience? Why will they read or listen? What do they need most from me? I also remind them to simplify without oversimplifying: technical detail is important, but clarity is essential, and if an idea can be explained in plain language, it should be. Another valuable exercise is to seek feedback from non-experts, because if a colleague from another field can follow your talk, chances are your intended audience will too. Finally, I suggest teaching whenever possible. Nothing accelerates audience awareness more effectively: students make it immediately clear whether you are speaking for yourself, your content, or for them.

A final thought

Recognising these three stages has shaped how I approach every form of written and oral communication, and it is a theme I also develop in my book titled “Effective Scientific Presentations: The Winning Formula”. At its core, the message is the same: scientific communication succeeds not when we impress with detail, but when we effectively transfer knowledge to an audience.

As I remind my PhD students, growing as a scientist means growing as a communicator. The most impactful communication happens when we put the audience first. That is the moment science truly reaches beyond the page or the podium and begins to do its work in the world.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Alan - I agree with your points! Faith