Hidden dangers of exertional heat exposure

Published in Biomedical Research

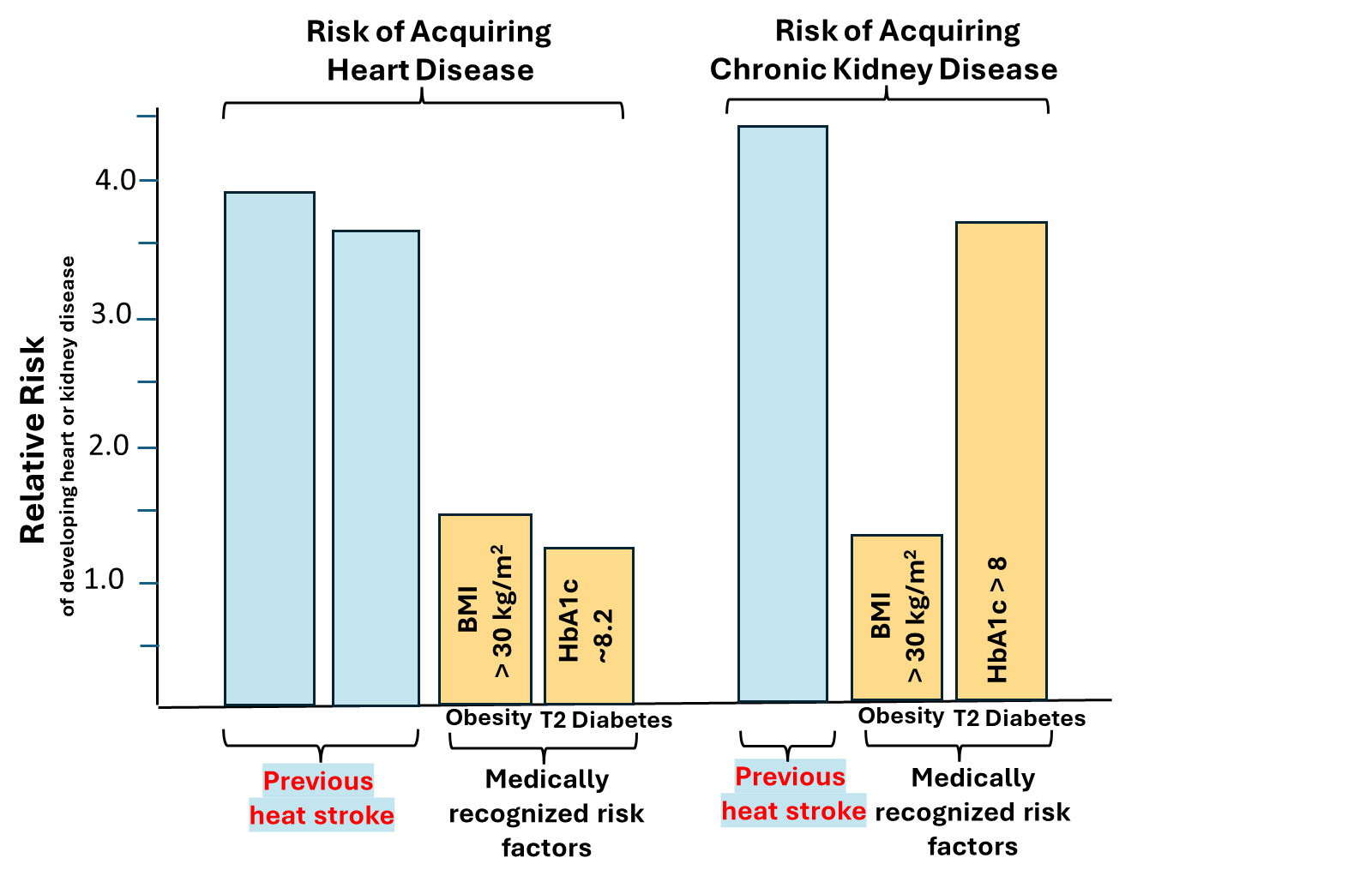

Heat stroke and other forms of severe heat injury are life threatening environmental challenges that are becoming more common with elevating global temperatures. Most medical practitioners are aware of the acute dangers of heat stroke, including multi-organ dysfunction and even death. However, in most settings, once symptoms subside, heat stroke patients are followed for only a few days and then sent home with mild precautions. Our lab became interested in the possibility of longer-term “hidden” dangers of severe heat stress that might contribute to chronic illnesses and heat sensitivities developing later in life 1–4. This is not a minor effect; in fact, the adjusted risk for heat stroke victims in developing heart or kidney disease later in life exceeds that of more well-known factors such as moderate obesity and Type 2 diabetes (Fig. 1)1–8; yet patients and physicians are not aware of this lurking medical danger that may someday manifest itself.

Since it is virtually impossible to directly study this phenomenon in a systematic way in humans, we set out to study it in mice using a of preclinical model of exertional heat stroke (EHS) that induces the acute symptoms seen in humans such as loss of consciousness, rhabdomyolysis, acute kidney injury, intestinal barrier injury and liver injury.9 This model takes approximately 2-3 hours of exercising in the heat until the mice lose consciousness (a defining clinical sign of heat stroke vs. other forms of heat injury).

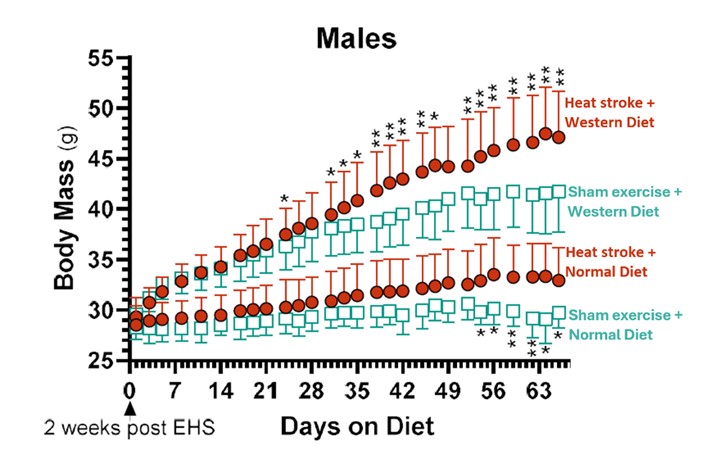

The mice wake up in a few minutes and most clinical blood biomarkers of health status return to normal within ~48 hrs. By all external appearances the mice completely recover. However, in this study we followed the mice for three months, a period believed to represent ~9 human years. This difficult series of experiments was undertaken by Jamal Alzahrani for his Ph.D. thesis. An important corollary that Jamal tested was whether the extreme but temporary stress of EHS caused the mice to be more vulnerable to secondary stressors later in life. We chose a Western diet as the secondary metabolic stress, known to induce heart and liver disease over time. After two weeks of recovery on a normal diet, half of the mice were put on a Western diet, loaded with fat and carbohydrates. The remaining half remained on a normal mouse diet. The results were surprising. Both male and female mice exposed to EHS while on a Western diet gained 16-20% more mass over the next 10 weeks of recovery compared to sham exercise controls on the same diet (Fig. 2).

Upon autopsy we also observed cardiac hypertrophy in EHS males on both diets. In general, male mice were more affected than females, but results remained qualitatively . The metabolism of heart ventricles was evaluated using an untargeted metabolomics approach. EHS mice exhibited a pattern of metabolites typical of a state of reduced “metabolic flexibility.” To explain, healthy hearts predominantly use fatty acids for metabolism but can call on other substrates if needed to maintain ATP generation. In many forms of heart disease, there is a shift toward using these alternative fuels, such as carbohydrates, ketone bodies and amino acids. Early use of these alternate metabolites suggests a loss of normal metabolic control and flexibility. Importantly, the body mass results point to some kind of global metabolic dysfunction as the mice lose their capacity to regulate mass over time. Other important and unexpected findings included a large loss of plasma protein (hypoproteinemia), a clinical feature common to heart failure patients10. Furthermore, the female EHS mice on Western diet exhibited greater susceptibility to liver injury, with increased fatty deposits in the liver tissue.

The significance of the results is that we can now confirm that heat stroke can have long-term and predictable impacts on mammalian health and metabolism, apparently over the lifetime of the animal (although this needs to be tested). The underlying mechanisms for these effects could be epigenetic because heat stress is a well-known activator of epigenetic pathways in most organisms11. Another possibility is that extreme heat stress can accelerate the body’s biological clock, making the organism more vulnerable to various forms of disease and dysfunction common to the elderly12. The pathophysiology of this phenomenon is not understood, and much work will be needed to peel away the onion layers of the biological processes responsible. Finally, with this or other relevant preclinical models it will now be possible to begin to design and test treatment and preventative measures that may someday reduce the health consequences and health care burden caused by excessive heat exposure, particularly when coupled with exertion, which is expected to increase in frequency and intensity as our planet continues to warm.

References

- Wang, J.-C. et al. PLoS One 14, e0211386 (2019).

- Tseng, M.-F. et al. Eur J Intern Med 59, 97–103 (2019).

- Tseng, M.-F. et al. PLoS ONE 15, e0235607 (2020).

- Kruijt, N. et al.. Sports Med Open 9, 33 (2023).

- Huxley, R., Mendis, S.,. Eur J Clin Nutr 64, 16–22 (2010).

- Rawshani, A. et al.. N Engl J Med 376, 1407–1418 (2017).

- Bash, L. D., et al. Arch Intern Med 168, 2440–2447 (2008).

- Garofalo, C. et al.. Kidney Int 91, 1224–1235 (2017).

- King, M. A. et al. Journal of Applied Physiology 118, 1207–20 (2015).

- Karki, S. et al. Curr Probl Cardiol 48, 101916 (2023).

- Murray, K.O. et al. Experimental Physiology 107, 1144–1158 (2022).

- Ledford, et al. Nature 636, 534–534 (2024).

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in