Hiding in plain sight - a potent neuronal K+ channel opener

Published in Healthcare & Nursing, Neuroscience, and Pharmacy & Pharmacology

The debate continues on how Thespesia populnea (porasu/miro/milo/haiti-haiti/Portia tree) found its way out of tropical Asia to pantropical beaches around the world, but it likely reached Polynesia via human hand and that may also be the case for the Caribbean. T. populnea is considered a sacred plant in Polynesian cultures, and was often planted in sacred groves and used to make religious sculptures. T. populnea wood was also used to make at least some of the famed rongorongo tablets in Rapa Nui (also known as Easter Island), which hold mysterious glyphs inscribed with an unidentified script suggested to hold an independently invented written language that has yet to be deciphered.

T. populnea wood is now used to construct furniture, musical instruments, kitchenware and canoe paddles, etc., while the bark makes effective rope and caulk. I first encountered T. populnea on a beach in St. John, US Virgin Islands (USVI), a US territory in the Caribbean Sea. Referred to by the local name of haiti-haiti in the USVI, one can also clearly see why it is sometime referred to as the Indian tulip tree, with its impressive flowers.

Importantly for our recently published study, T. populnea has enjoyed widespread use in indigenous medicine practices across its range - it has been used for wound-healing, skin lesions and fractures, and has been studied for its antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, and bactericidal properties. T. populnea extracts are tolerated at extremely high doses (2g/kg) in rodents, in which T. populnea bark extract has also been shown to have antinociceptive effects.

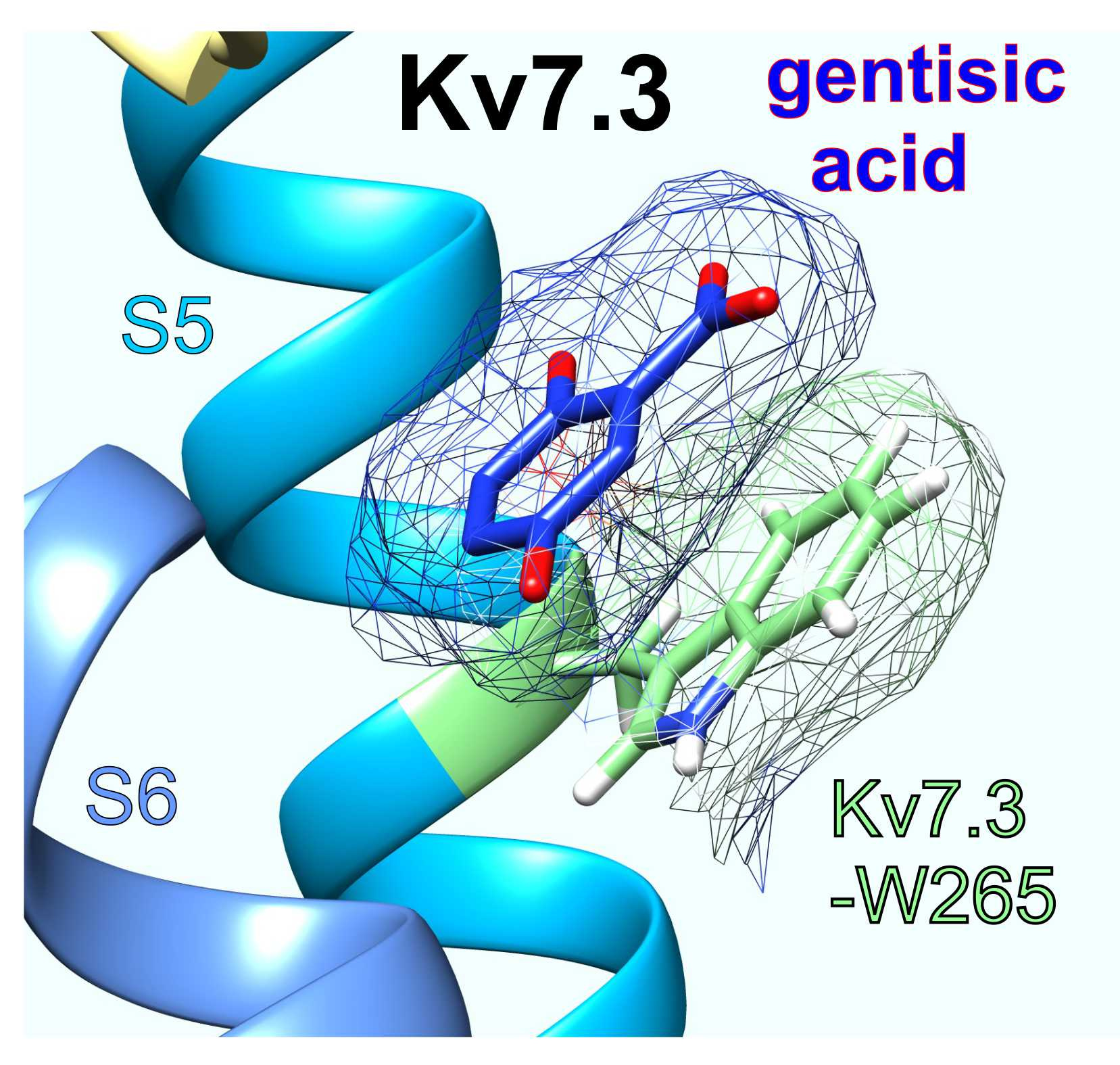

In a screen of 1,444 plant extracts, most of which we collected under federal permit in National Parks in California and the USVI (St. John and St. Croix) we found that T. populnea extract collected from a beach in St. John opened the neuronal Kv7.2/7.3 heteromeric voltage-gated potassium (Kv) channel that is crucial for normal neuronal excitability. Having previously found that many of our extracts contain sufficient tannic acid to open Kv7.2/7.3, and intending to find compounds other than tannic acid, we counter-screened against the immune cell Kv channel, Kv1.3, which we previously found to be inhibited by tannic acid. This led us to T. populnea and then a functional screen of the most prevalent metabolites within it revealed gentisic acid as the active component. Stunningly, gentisic acid is to our knowledge the most potent known opener of Kv7.3 (EC50 of 790 pM) and perhaps Kv7.2/7.3 (2.8 nM), which it achieves by, according to our experimentally validated docking studies, binding incredibly tightly to a tryptophan in Kv7.3 transmembrane segment 5 that is also crucial for binding of retigabine, the first-in-class Kv7.2/7.3-opening anticonvulsant. Gentisic acid is also highly Kv7 isoform selective; it does not open homomers of any of the other four Kv7 isoforms.

Figuring out how the tiny gentisic acid achieves such high potency and selectivity, even more remarkable when one considers that Kv7.2, 4 and 5 each also boast an equivalent tryptophan, could pave the way for a new chemical class of anticonvulsants, and gentisic acid itself will also be the subject of our intense further evaluation in this area. It is extremely well tolerated (up to at least 2g/kg in mice), hence its use in over-the-counter skin-whitening products for decades.

Perhaps most remarkably, gentisic acid has been hiding in plain site - it is an active metabolite of aspirin and is in many of the foods we eat, including apples, blackberries, kiwi, olives and avocados - yet it took a trip to the Caribbean and a broad screen of 1,444 plant extracts for us to discover the Kv7.3-opening potency of gentisic acid. As it turns out, Polynesians from the remote Rotuma Dependency, north of Fiji, already figured out long ago that T. populnea has anticonvulsant properties - we just uncovered the mechanism. This has been a common theme in our work - whether we are guided by the wisdom of indigenous medicine practices in targeting specific plants for study, or in this case conducting a random screen, we invariably end up reinforcing and adding mechanistic detail to what has already been found hundreds or thousand of years ago by shamans and other medicine men and women. As my lab widens its search for medicines in plants to a greater geographical range, we anticipate uncovering more complex, perhaps previously unknown plant metabolites, with further therapeutic potential.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Chemistry

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the chemical sciences.

Your space to connect: The Psychedelics Hub

A new Communities’ space to connect, collaborate, and explore research on Psychotherapy, Clinical Psychology, and Neuroscience!

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

f-block chemistry

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Experimental and computational methodology in structural biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in