Hip clues about anthropoid primate evolution from 30 million years ago

Published in Ecology & Evolution

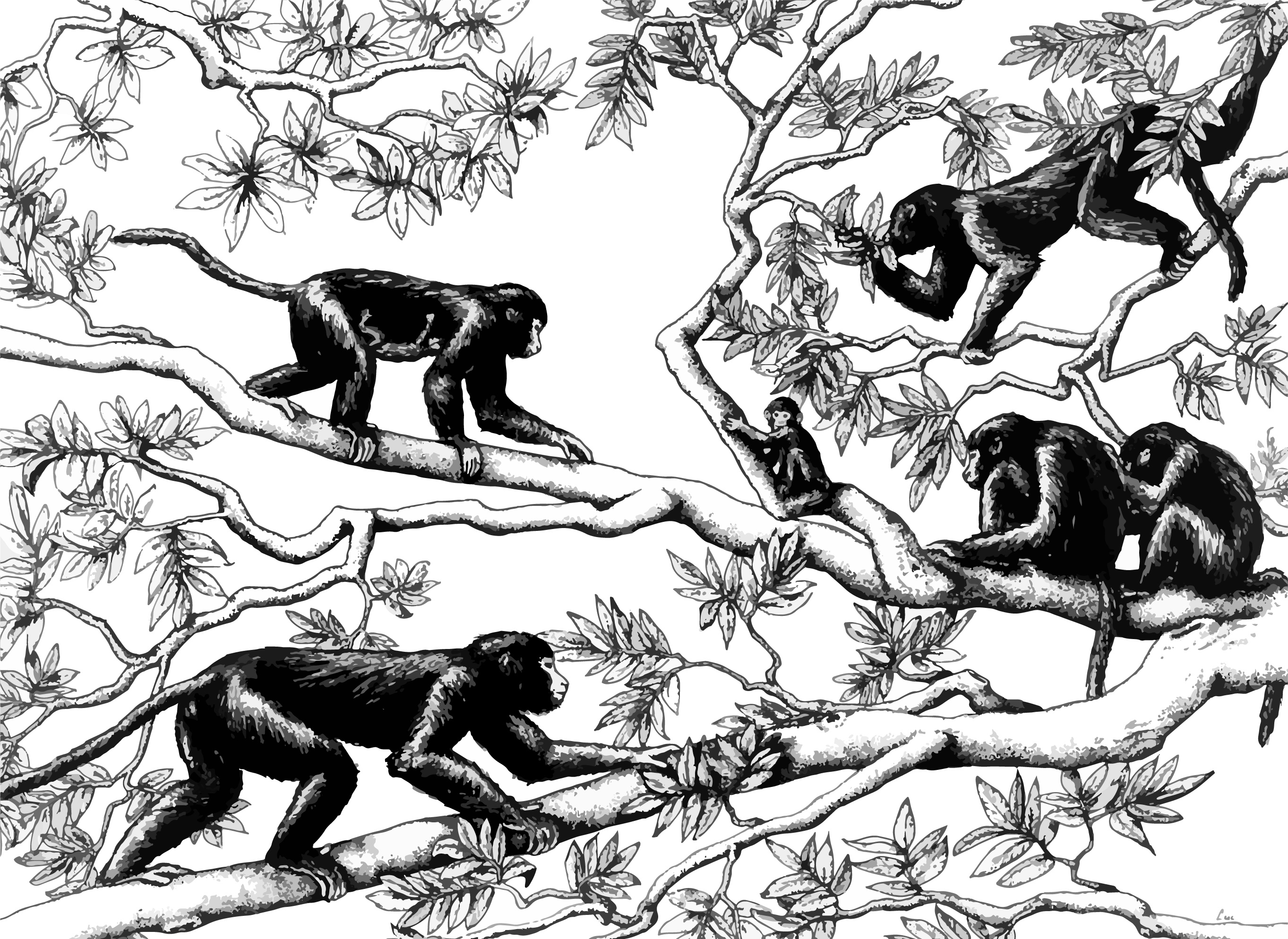

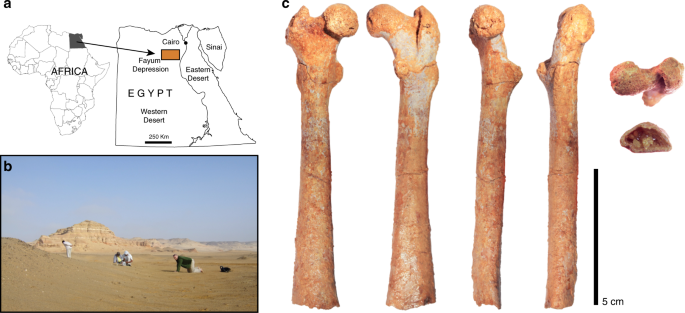

As I age, I am traveling further back in time. This might seem counterintuitive, but as a paleontologist and evolutionary biologist, I continually work towards better understanding evolution in deep time. This passion began when I was a child—in amazement—I would wander around ruins of old castles and medieval farmhouses in my home country of Spain. In my late teens I began participating in Pleistocene paleontological digs and I would imagine the lives of these other humans—individuals of other species of our own genus Homo—as they first settled and spread outside the African continent around 2-1 million years ago. For my PhD dissertation, I started to connect the morphological dots between our Miocene great ape ancestors and the first members of the human lineage (by looking at the time period between 12-6 million years ago). I am now a senior researcher at the American Museum of Natural History. However, when I was a postdoc at Stony Brook University (SBU), I had just published a study looking at the morphometric femoral affinities of the early biped Orrorin tugenensis when my SBU colleague and co-author of this study, Erik Seiffert (now at University of South California), came into my office. He planted a nice and orange fossil femur on my desk and told me that it represented the most complete femur ever found of Aegyptopithecus zeuxis (see below). Aegyptopithecus was a primate that roamed Egypt during the Oligocene (~30 millions of years ago) and it is widely accepted as an advanced basal catarrhine primate, in other words, a “forerunner” of both hominoids (the ape and human lineage) and Old World monkeys. Erik and his team, including co-author Hesham Sallam, had found the new specimen in their last campaign in 2009, and he asked me if I could study the femur and see if there was anything interesting about the anatomy. This Aegyptopithecus femur constituted a great opportunity to glimpse into the evolutionary divergence between hominoids and Old World monkeys based on their hip morphology, which tightly relates to their divergent locomotor behaviors (see a representative of each group in the poster image above). Even better, it represented and incredible chance for me to travel even further back in time.

The new Agyptopithecus zeuxis DPC 24466 from the Jebel Qatrani Formation in Egypt (DPC stands for “Duke Primate Center,” where the fossil specimen will be finally curated). Missing only the distal portion, it preserves ~11 cm of its original length.

In the early days of paleontology, researchers would study a fossil and subjectively interpolate its phylogenetic position and evolutionary role. Scientists today now benefit from the myriad of available quantitative methods to guide our conclusions. For this study, my colleagues and I relied on George Gaylord Simpson’s 1944 “adaptive landscape” ideas applied to phenotypes (i.e., morphologies) and the evolutionary modeling subsequently developed by Hansen (1997), Butler and King (2004), and Ingram and Mahler (2013), among many others. The same approach had been previously used by Mahler et al., (2013) to study the macroevolutionary landscape in island lizard radiations, and inspired us to investigate the hominoid–Old World monkey divergence. Our study shows that Aegyptopithecus preserves an ancient hip morphology not present in living anthropoid primates. As far as the hip is concerned, it seems that apes, humans, and Old World monkeys have all departed ways long ago (which would explain why they move around so differently).

Finally, this study was the result of the work of a great team, including my colleagues mentioned above, as well as Lissa Tallman, Ashley Hammond and John Fleagle. They all contributed extensive amounts of data, as well as expertise in the methods, functional morphology and primate evolution necessary to develop this project. I am grateful to all of them for joining in on the time-traveling experience, to go back 30 million years and to envision Aegyptopithecus hanging out in a tree.

*Poster image: Play session between adolescent male chimpanzee, Faustino, (Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii) and adolescent male olive baboon (Papio anubis). Gombe Stream Research Center, Gombe National Park, Tanzania. © Kristin J Mosher (www.kristinjmosherimages.photoshelter.com)

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in

Thanks for this article. Yes, the OWM/ape LCA (last common ancestor of catarrhine monkeys & hominoids) was an arboreal animal, different from both extant OWMs & extant hominoids (apes & humans). Whereas the New World monkeys probably almost exclusively remained arboreal, the OWMs seem to have became partly terrestrial & partly arboreal ("terrarboreal"), spending time on the ground & time in the branches, but the hominoids became partly aquatic & partly arboreal ("aquarboreal") in the swampy forests where they typically fossilized, spending time climbing vertically in the branches & time wading bipedally in the forest swamps, probably in search of AHV (aquatic herbaceous vergetation), possibly not unlike extant bonobos wading for waterlilies or lowland gorillas wading for papyrus sedges, frogbit or other floating herbs (see our 2002 TREE paper, see below). Google e.g. "bonobo wading" or "gorilla bai". That implies that the early hominoids were already "vertical", as still is the case in gibbons & siamangs (who have become vertical arm-swingers) as well as in humans (who became upright waders & walkers), whereas the Asian great apes became suspensory below-branchers (orangutans) and the African apes became knuckle-walking chimps, bonobos & gorillas. See our paper Verhaegen, Puech & Munro 2002 "Aquarboreal Ancestors?" Trends Ecol.Evol.17:210-217, or for an update google "two incredible logical mistakes 2019 verhaegen".