How a zoo elephant helps us understand megaherbivore migrations

Published in Social Sciences, Earth & Environment, and Ecology & Evolution

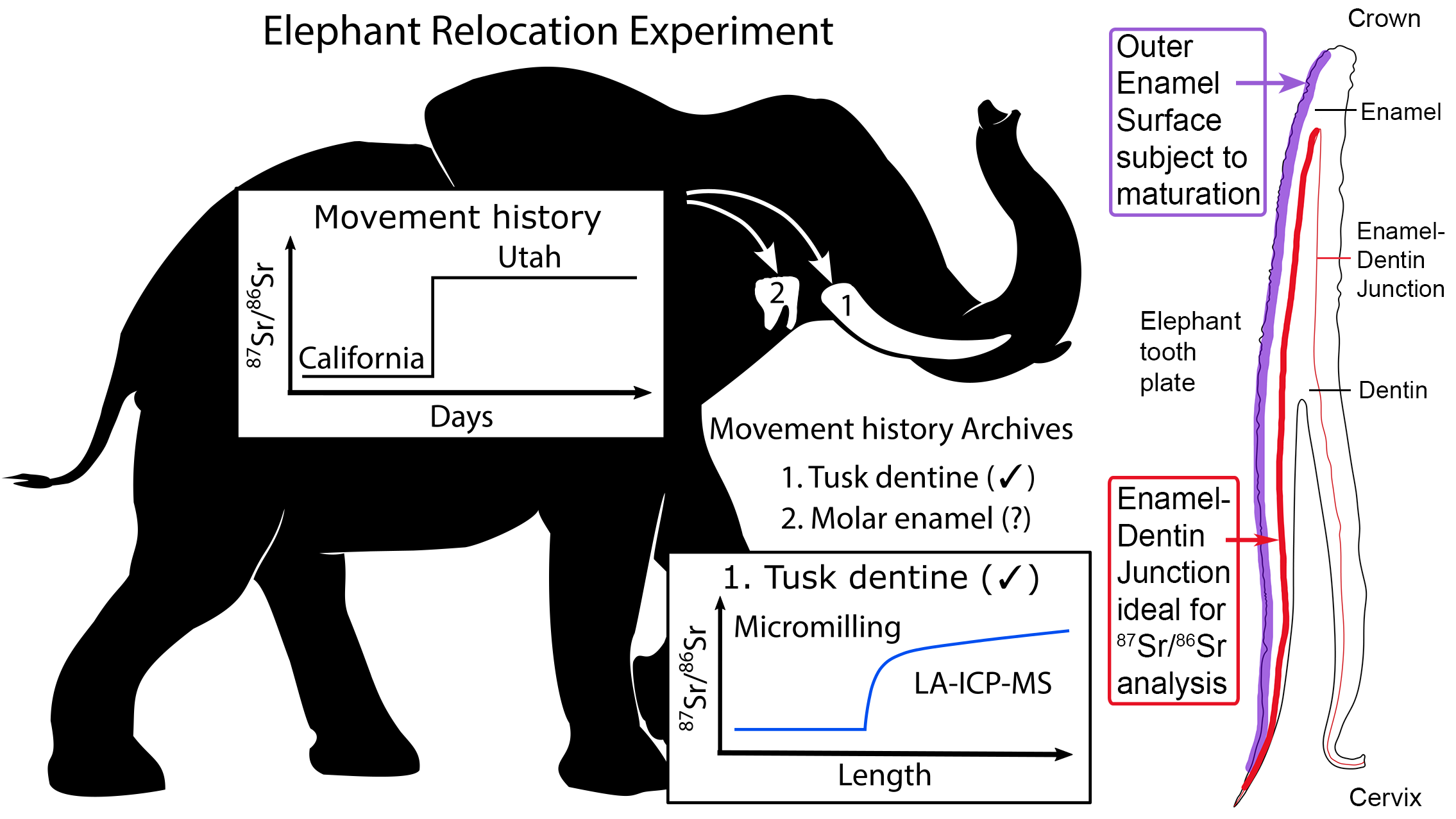

As a team who study the ecology of extinct animals, we have been fascinated by the question of how megaherbivores such as mammoths and mastodons migrated on the landscape. Strontium (Sr) isotope analysis is a powerful tool in movement and migration reconstructions because Sr signatures vary geographically. Sr in rocks and soils are absorbed into water and plants. As animals eat and drink, they pick up this environmental signature and store it in their teeth, preserving a series of environmental exposures like historic archives. By analyzing Sr isotopes in teeth, we can reconstruct the migration history of extinct animals.

One of the overarching questions in the research community was how tooth enamel records the longitudinal Sr exposures as an elephant moves from one place to another. In this study, we were extremely fortunate to have Misha, a 27-year old female African elephant, to join us together in telling the story of her epic move from Six Flags Discovery Kingdom in Vallejo, California, to the Hogle Zoo in Salt Lake City, Utah.

In early September 2008, a sad news hit the Salt Lake City public, with Misha’s death at the Hogle Zoo (Original report by Desert News). One of the leading scientists of our team, Professor Thure Cerling of the University of Utah, quickly realized that this could be an exceptional research opportunity. Professor Cerling had been working with the zoo for some years because of his interest in stable isotopes as a tool to reconstruct the diet of both modern and fossil mammals. “Elephants have a rich fossil record, and I was actively working with Save The Elephants (an NGO) on conservation projects in Kenya and had an interest in elephant histories. So this elephant (Misha) figuratively ‘fell in our lap’ at the time”.

“On hearing the morning radio program that Misha had just died, we realized that this could be a great opportunity for further understanding the history of elephants. We called the zoo and the then-current veterinarian, Dr. Nancy Carpenter, welcomed us to come down as she was just about to do an autopsy on Misha. In collaboration with the zoo, we were able to work on the molars from one side of her mandible, and one of her tusks. All this happened so quickly that we did not quite know what we had – but we soon discovered that Misha had been in Salt Lake City for only a few years after moving from California. So we realized that we could use both the molar and the tusk to look at isotope turnover in elephants”. This led to the current study on Sr isotopes in Misha, documenting the data corrections between her molar and tusk. “We later found out that we were fortunate in our timing: had we waited a few days before making our phone call, the carcass would have been buried under 10 feet of soil and could not have been retrieved!”, said Professor Cerling.

To track Misha’s move from California to Utah, we used the laser ablation technique guided by a microscope, which allows a tiny amount of dental material to be analyzed by the instrument. We did this with multiple passes along the growth direction of the tooth, so that we can map out how Sr isotopes vary within her tooth enamel. Our data showed that Misha’s outer enamel is influenced by the complex enamel maturation process that tends to attenuate the Sr isotope record, while her innermost enamel layer preserves the original record very well and is the ideal place for sampling. We then used this variation pattern to guide our modeling efforts (published in Yang et al., 2023) to reconstruct Misha’s Sr exposure history associated with her move. The modeling work was in collaboration with another leading scientist of our team, Professor Gabriel Bowen, who leads a summer short course (SPATIAL) on isotopes and geospatial statistics.

Our study not only adds to our understanding of how tooth enamel records an animal’s Sr isotope exposure, but also helps to reconstruct animal migrations from Sr isotope analysis. It can be applied to studies of paleobiology, to answer how megaherbivores migrated in the past. It can also be applied to studies of modern conservation and forensics, to trace the origins of illegal ivory trade and other forms of wildlife trafficking.

Professor Cerling also spoke about the important roles of serendipity in his own research career. This study can be traced back to his research seminar at the University of Michigan in early September 2006, where he met Professor Dan Fisher who had been studying mammoths and built a customized bandsaw for cutting mammoth tusks. After we obtained Misha’s tusk, Professor Fisher kindly helped another leading scientist of our team, Professor Kevin Uno, to prepare the tusk for a series of isotope analysis, ultimately generating the data used in the current study.

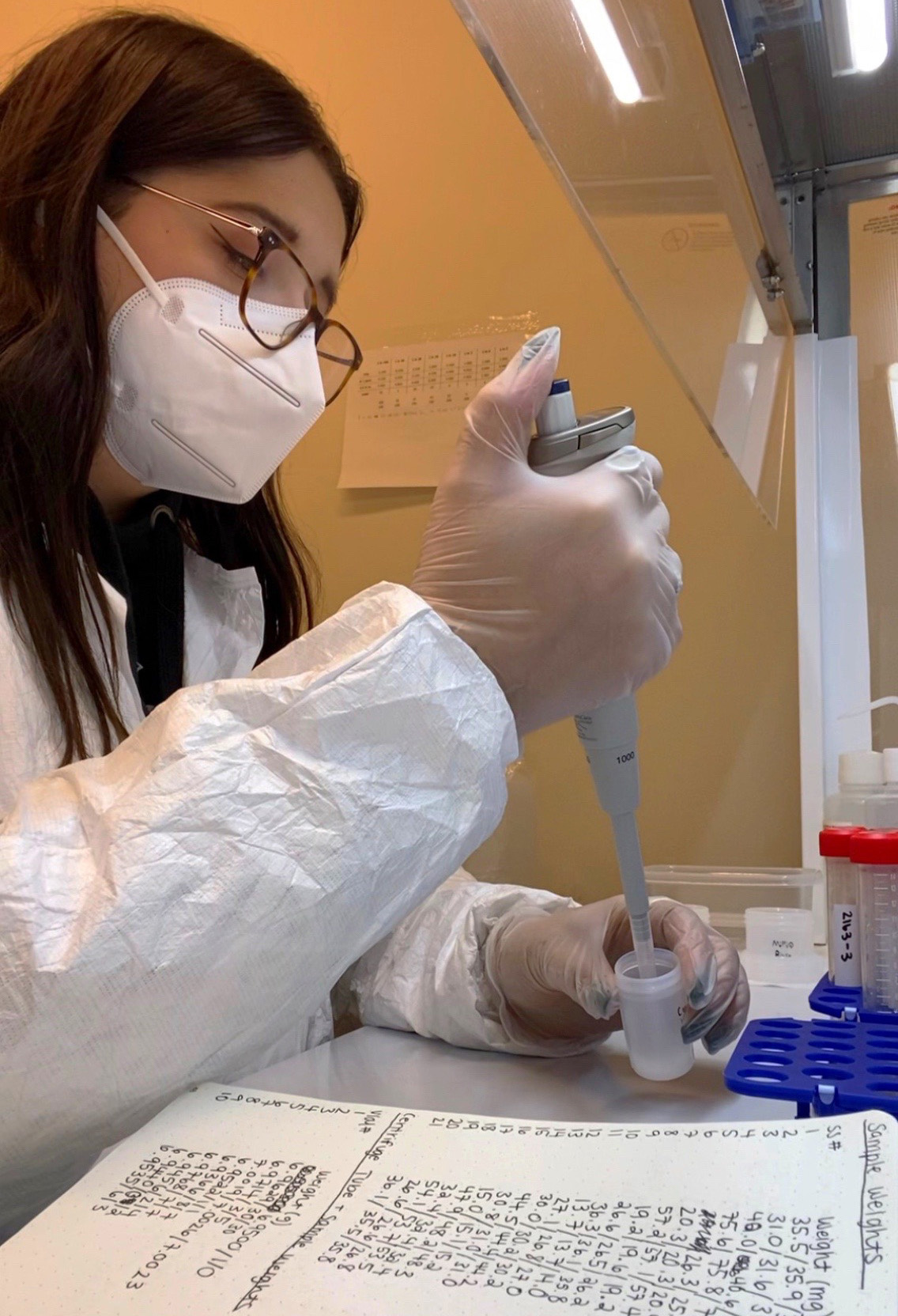

Katya Podkovyroff (her website & Instagram) was an undergraduate research assistant at the University of Utah when she joined the team. She did most of the lab analysis that generated the data used in the current study. Here’s some behind-the-scenes story by Katya.

Katya Podkovyroff working in the Earth Core

ICP-MS laboratory at the University of Utah.

“When I first stepped into the Earth Core-ICP-MS laboratory at the University of Utah in 2021 as an undergraduate, I had no idea how much it would shape my academic journey. Within my first semester, I began working with Dr. Diego Fernandez, learning how to process Sr isotope analysis on bone, enamel, ivory, and plant material. It was in this lab where I got my first hands-on experience with scientific research, and I immediately fell in love. One of the most thrilling aspects of the job was learning that each sample carried a history, a mystery waiting to be unraveled through chemical signatures. Dr. Fernandez encouraged my curiosity, and over time, I became involved in refining our lab procedures for bioapatite samples—anything that was enamel or bone”.

“Among my various lab responsibilities, one project became particularly special: studying the movement history of Misha. This endeavor, which ultimately became my undergraduate senior thesis, involved analyzing Misha’s Sr isotopic signatures preserved in her teeth. I collected samples from her tusk using a micromill sampling device, and food samples provided to Misha at the Hogle Zoo. The samples went through multiple stages of processing—concentration calculations, purification, and ICP-MS analysis—before overarching data interpretation could be done. This research was both exciting and challenging: sampling ivory required extreme precision, as even minor contamination could alter results, and isotope purification is a meticulous and time-consuming process. The most rewarding aspect of this project was its broader implications beyond a single case study: it has applications in modern conservation efforts, with the ability to trace the origins of illegal ivory trade. Whether it was the satisfaction of a successful analysis, the challenge of refining protocols, or the simple joy of hours in the lab, my work in the ICP-MS lab shaped my passion for research and set me on the path to pursuing a PhD at the University of Oregon, where I explore the intersection of biogeochemistry, paleoecology, and pressing environmental issues.”

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in