How an ancient autophagy pathway shaped glycogen-based energy strategies in animals

Published in Earth & Environment, Ecology & Evolution, and Protocols & Methods

Why do oysters rely so heavily on glycogen?

For many years, our group has been intrigued by a simple but fundamental question: why do oysters and other molluscs rely so strongly on glycogen, rather than lipids, as their principal long-term energy reserve?

In most animals, especially vertebrates and insects, lipids dominate energy storage due to their high energy density. Yet oysters accumulate extraordinary amounts of glycogen and mobilize it efficiently during prolonged stress, starvation, and reproduction.

Is this glycogen-centered metabolic strategy merely a lineage-specific peculiarity of molluscs, or does it reflect a deeper evolutionary logic shared across animal lineages?

To address this, PhD student Liting Ren began by compiling and comparing biochemical composition data across a wide range of animals. This analysis revealed that oysters and other molluscs consistently stand out as extreme examples of glycogen-centered energy storage. However, while the ecological and physiological patterns were clear, the molecular mechanisms and evolutionary origins underlying this strategy remained largely unexplored.

Following glycogen under starvation: which pathway sustains oysters?

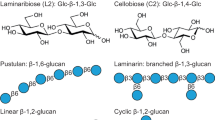

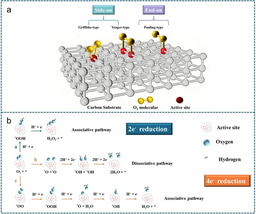

Our next step was to ask how glycogen is actually mobilized in oysters under nutrient limitation. Two main catabolic routes are possible:

- the canonical cytosolic phosphorolysis pathway, and

- the non-canonical autophagy-dependent pathway known as glycophagy.

Using a controlled fasting–refeeding experiment in Crassostrea gigas, we examined temporal changes in gene expression and cellular signals associated with these pathways. The results revealed a striking division of labor over time. Genes involved in phosphorolysis were rapidly induced during early starvation (days 1–3), whereas genes associated with glycophagy were strongly upregulated during prolonged starvation (days 5–14).

Histological and immunochemical analyses further showed that autophagy signals closely tracked glycogen depletion, while lipid stores remained largely unchanged. Together, these findings suggested that glycophagy is not a minor auxiliary pathway in oysters, but rather a key mechanism supporting long-term energy demands under stress.

Identifying the molecular driver: STBD1-mediated glycophagy

Selective autophagy depends on cargo receptors that recognize specific substrates and deliver them to lysosomes. This prompted us to focus on autophagy receptors as potential molecular determinants of substrate preference.

Comparative expression analyses showed that, under nutrient deprivation, the glycophagy receptor STBD1—rather than the lipophagy receptor p62—was dynamically regulated and actively consumed in oysters. This pointed to STBD1 as a central player in oyster energy metabolism.

To test whether STBD1-mediated glycophagy is functionally conserved, we characterized its interacting partners. By combining RNA co-localization and protein–protein interaction assays, we identified GABARAPL2, an ATG8 family protein, as the primary STBD1-binding partner in oysters. Intriguingly, our genome-wide survey revealed that oysters lack several ATG8 paralogs known to mediate lipophagy in vertebrates.

These findings together support the existence of a complete, STBD1-dependent glycophagy pathway in oysters, while simultaneously suggesting a reduced or altered lipophagic capacity—an observation consistent with their glycogen-centered energy strategy.

A structural clue: why oyster STBD1 binds glycogen so efficiently

One of the most striking discoveries emerged when we compared the structure of STBD1 across taxa. In oysters and other molluscs, the carbohydrate-binding CBM20 domain is positioned at the N-terminus, whereas in vertebrates it resides at the C-terminus.

Through structural modeling and molecular dynamics simulations with branched maltotetraose, we found that although CBM20 adopts a conserved β-barrel fold across species, the energetic contribution of one binding pocket (Site 2) is substantially enhanced in oyster STBD1. As a result, oyster STBD1 exhibits a much stronger predicted affinity for glycogen than its vertebrate counterparts.

We then experimentally validated this prediction by combining domain rearrangement, protein purification, and heterologous cell assays. Relocating the CBM20 domain from the N-terminus to the C-terminus significantly weakened glycogen binding and degradation, demonstrating that domain position alone can profoundly alter glycophagic efficiency.

Reading evolutionary history from protein architecture

These results raised a broader evolutionary question: does STBD1 structure record an evolutionary shift in metabolic strategy?

PhD student Yitian Bai led a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of CBM20-containing proteins across metazoans. This revealed that the N-terminal CBM20 configuration represents the ancestral state of STBD1, while the vertebrate C-terminal arrangement emerged later through domain rearrangement at the root of chordates.

Rather than indicating a simple gain or loss of function, this transition appears to reflect a rebalancing of energy utilization strategies. Glycophagy was retained in vertebrates but became less dominant, coinciding with the increasing importance of lipophagy and lipid-based energy storage.

Open questions and future directions

Looking beyond our core findings, this study opens several new avenues for exploration. In lophotrochozoans, STBD1 and other CBM20-containing genes have undergone extensive lineage-specific expansions, suggesting previously unrecognized diversification of glycogen-handling strategies. In contrast, echinoderms and arthropods appear to lack canonical STBD1, raising the possibility that glycophagy in these groups relies on alternative receptors or distinct mechanisms altogether.

Even more intriguingly, STBD1-like genes are present in some protists, hinting that elements of glycogen-directed autophagy may predate animal multicellularity—or, alternatively, reflect ancient horizontal gene transfer events later co-opted during metazoan evolution.

A broader perspective

Taken together, the evolution of STBD1 provides more than a case study in protein domain rearrangement. It offers a molecular window into how conserved cellular processes such as autophagy are repurposed to meet the energetic demands of different animal lineages, and how metabolic pathways themselves diversify over deep evolutionary time.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

From RNA Detection to Molecular Mechanisms

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 05, 2026

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in