How do cells remember their past? An unexpected role for genome folding

Published in Biomedical Research and Law, Politics & International Studies

As simple as it may sound, one of the most outstanding questions in developmental biology is how cells remember who they are. When a multicellular organism develops, cells progressively specify the genes to be expressed and repressed in order to grow into particular cell types. To do this, cells rely on epigenetic regulation that introduces heritable modifications of chromatin to control gene activity.

These epigenetic states are stable over time: they are maintained through cell divisions, and sometimes the entire lifetime of the organism, a phenomenon often referred to as cellular memory. Although cellular memory is a concept central to development, its molecular basis is only partially understood.

The question

The organisation of chromatin is not random inside nuclei. Research in the past 10 years revealed that chromatin folds into complex 3-dimensional (3D) structures that are related to its activity states. Importantly, 3D genome organisation is not just a side effect: it plays important roles in cellular processes, including the epigenetic regulation of gene expression. As a result, chromatin folding is increasingly considered part of the epigenome.

Our prior work showed that a transient epigenetic perturbation can be recorded by chromatin and drive aberrant phenotypes in Drosophila. This made us wonder if mammalian stem cells could also record past perturbations? If so, how is such information stored?

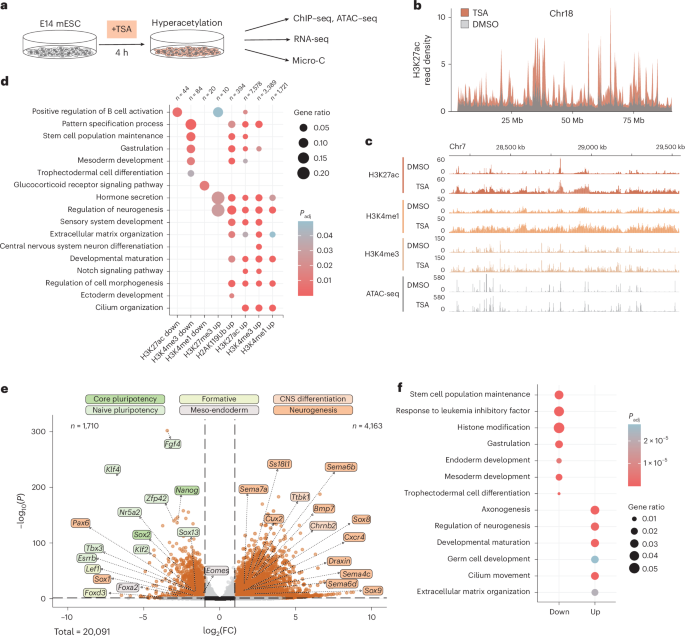

The surprise

To test this idea, we transiently inhibited a group of enzymes in mouse embryonic stem cells, leading to the global disruption of gene expression, epigenetic landscape and chromatin folding. The idea was then simple: perturb the cells, remove the perturbation and see if cells “remember”. However, stem cells are very plastic and so when the inhibitor was washed out, nearly all changes seemed to reverse. This observation entirely contradicted our hypothesis that stem cells might memorize stressful exposures. Although disappointing, we resisted the temptation of stopping there. Could such a profound perturbation really leave no trace at all?

The turning point

We eventually decided to look more closely. This meant going back to the data again and again, over more than a year, trying different ways of stratifying it, re-running analyses, and repeating experiments. Eventually, a more complicated picture started to emerge. Most genes really did recover, but a small subset did not quite go back to normal. The same was true for certain aspects of 3D genome folding, which seemed to retain traces of the perturbation.

What we really had not expected was that this happened without stable changes in classical epigenetic marks, like histone modifications. This made us question our initial idea that epigenetic memory in stem cells would be encoded mainly through these marks. Instead, the data kept pointing us toward chromatin organisation itself, suggesting it might have a role in cellular memory that we hadn’t anticipated at the start.

But then we started to wonder: if some changes in 3D chromosome folding do not fully reverse, maybe the cells actually recorded the perturbation they suffered? Should this be the case, if we perturbed them a second time would they recognize that this was a second event and respond differently? So, there we went, re-running the experiment and adding a second perturbation followed by recovery, and this time we nailed it: hundreds of genes were no longer able to recover their initial state. Even more intriguing, genes that failed to recover had very strong 3D chromatin structures around their regulatory elements. We now knew that we really were onto something significant!

The obstacle

The idea that 3D genome conformation could store information on the cells’ past and give rise to lasting changes in gene activity was exciting – but also challenging. Demonstrating causality would require manipulating chromatin architecture to induce cellular memory.

Initially, we considered using genome editing tools to manipulate genome folding at selected loci. But which ones? Our epigenetic perturbation affected more that 6000 genes, giving rise to memory only at a small fraction. The combinatorial complexity of regulatory mechanisms, and which would be most likely to respond to chromosome folding, quickly became overwhelming.

Another possibility was to use molecular tools that uncouple epigenetic chromatin modifications from genome folding. This however, was more a dream than a real possibility, given the complex interplay and functional redundancy among chromatin regulators.

The importance of scientific discussions

Due to the challenging nature of the project, we spent years showing unpublished data and openly discussing half-formed ideas and doubts. Such sharing and openness were key to progress, not just for troubleshooting, but for seeing the problem differently.

One of these discussions, with Robert Klose from Oxford University, proved decisive. Through this exchange, we identified an existing experimental system that would allow us to functionally test the role of the 3D genome in cell memory. By kindly sharing a stem cell line with us, we were finally able to experimentally demonstrate cellular memory for hundreds of genes that depended on 3D genome structure.

The future

The idea that 3D genome folding is a carrier of cellular memory has its particularity and raises many new questions. For example, nuclei are remodelled and chromosomes are condensed every time cells divide. So how does regulatory information stored in chromosome organisation survive cell division?

More broadly, cells are constantly exposed to cycles of perturbation and recovery – in response to developmental and environmental cues, or following treatment in disease. Investigating how cells record and integrate past stimuli will be key to understand both healthy development and pathological states.

Watch a video summarizing the main findings here https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=VtmWJDiSLho

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Genetics

This journal publishes the very highest quality research in genetics, encompassing genetic and functional genomic studies on human and plant traits and on other model organisms.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in