How do you measure a surface?

Published in Materials

FOUNDATION OF THE SURFACE-TOPOGRAPHY CHALLENGE

- How can the topography of a surface be modified to improve performance?

- Can we roughen or smoothen a part to make it look and feel nicer, to make it stickier or more slippery, to make it more damage-tolerant for a longer lifetime?

People have been studying this question for at least 100 years, and the answer is still elusive. Ironically, the science of topography-dependent properties is not the problem; the problem is in measuring surfaces accurately.

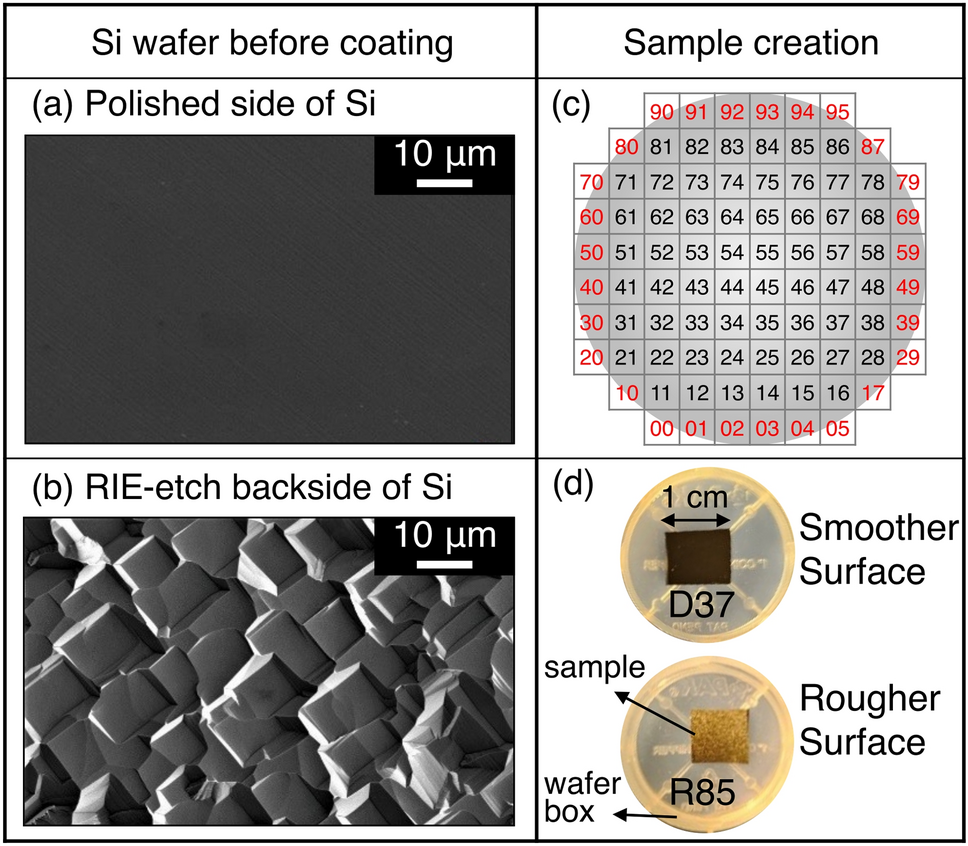

To demonstrate current limitations, and to help forge a better approach, we launched the Surface-Topography Challenge. We put out a call, back in 2022, inviting anyone to volunteer to measure and report on a common surface.

Initially we feared that only a few labs might participate, but we had an overwhelming response from the international community. In the end, 153 people came together—from scientific researchers to manufacturing engineers—to work collaboratively to solve this problem. Participants hailed from 20 countries, spanning every continent except Antarctica.

STANDARDIZING THE REPORTING AND ANALYSIS OF TOPOGRAPHY

Throughout the work, the Challenge was hampered by the very problem it was trying to solve: wide disagreement over how to measure, analyze, and report topography. Specifically, there were three obstacles to overcome:

Obstacle 1: How to combine disparate measurements? We received more than 2,000 different measurements, extracted from 50 different tools, comprising 12 different measurement techniques. We asked all authors to send measurements in the raw, native file format directly from the instrument, if possible. So the first step was getting all of these measurements into a single platform. We chose to use the open-source platform Contact.Engineering, which was developed years earlier by some of the organizers of this Challenge. We needed to aggregate all measurements, such that they could be shared with the organizers, compared against each other, and eventually shared publicly.

Obstacle 2: How to standardize the data analysis? Different companies, research labs, and groups have different conventions for how to process the data after it is collected. Choices such as tilt-correction, filtering, artifact removal, and filling in missing data can have a big impact on the final results. So, the second step was to develop a single, standardized workflow. We did this as described in the paper and applied it to all of the raw data, regardless of source.

Obstacle 3: How to choose which parameters to report? There are dozens of different roughness metrics in common usage. Each one has advantages and disadvantages, and many are specialized for a certain set of applications or process conditions. Here we reported on two parameters that were chosen to apply as broadly as possible:

- The root-mean-square (RMS) height, as a function of analysis size.

- The power spectral density (PSD) of height, which separates the contributions to topography from various length scales.

Even after all this standardization, the submitted data showed incredible disagreement. The RMS height, computed from the raw measurements of different groups, spanned from less than 100 pm to more than 10 microns—a 1-million-times difference in measured parameters for the same surface! While a surface-topography expert might have predicted this wide variability, it demonstrates to a wider audience how much variation there can be in surface measurements.

Finally, we worked to establish the “true” topography of the surface. We accounted for the length scales of the various measurements. We corrected for artifacts based on the resolution of the imaging tools. And we combined all the different measurements and techniques, using a majority-rules approach. In the end, we were able to establish a single consensus description of the comprehensive topography of the entire surface.

SMOOTHING THE WAY FOR FUTURE ADVANCEMENTS

Overall, the Challenge was a bit more challenging than we had expected. We didn’t anticipate the sheer logistics of processing requests, sending samples, and clearing customs. Then, because of inevitable delays (and maybe some procrastination by the participants!), we had to extend the original deadline from August 2023 to March 2024. Finally, we underestimated the difficulty of getting 153 people to agree on *anything*, especially a scientific investigation and publication. As a result, our optimistic plans for the publication date were pushed back several times.

But ultimately the very purpose of the Challenge was to identify the obstacles and complexities of measuring surfaces, and to take a stab at overcoming some of them. We believe the three-year collaborative effort has accomplished three key achievements:

Achievement 1: Best practices for topography measurement. Together, the 153 authors on the paper identified three key lessons from this international collaboration. We then paired them with three “Topography Best Practices” to move the field forward. (See the full paper for details!)

Achievement 2: A data set and a repository. All of the data from this study is freely available for reuse and reanalysis. The open-source web application used in this investigation allows anyone to view, download, and reanalyze all measurements.

Achievement 3: A benchmark surface. Now that we have these extremely well-characterized surfaces, we imagine they can be used for comparison, calibration, and training, or for measuring properties and connecting these back to the surface’s topography. We will continue sending these samples to any requesters, at least until the current supply is exhausted.

In the end, we hope that this is not the end of the story, but just the beginning. We hope that this international collaboration moves the field of surface science forward in the quest to design, manufacture, and control surface topography for optimal surface performance.

Follow the Topic

-

Tribology Letters

Tribology Letters is a peer-reviewed journal dedicated to advancing the science of tribology and its practical applications.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

World Tribology Congress 2026, Rio de Janeiro

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in