How we respond to stressors

Published in General & Internal Medicine

All of us felt the impact of the COVID -19 pandemic, from the remarkable restrictions on our movements, to the changes at work and at school, the changes imposed on caregivers from moms to middle–aged sandwich generation women with both elderly parents and young children to wrangle. At the School of Medicine, students were briefly dismissed from clinical activities (at the national level), then returned with many restrictions, classes became either remote or conducted with the now-infamous six-foot distancing between room occupants, lab work continued but in shifts to avoid personal contact, and a beautiful new health education building was converted for potential use as a spillover hospital for infected patients (which fortunately was never used). We were physically and emotionally confined. Our usual outlets – restaurants, bars, social clubs, sports – were restricted or eliminated, and we feared for our very lives as the virus spread (and mutated) and the death rate, especially among the elderly, increased. We took the measure of prior pandemics. The “Spanish flu” of 1918-19 killed the young and healthy. Small wonder that anxiety and depression rose. As physicians we worried that our patients would compound their other problems with increased anxiety and depression, substance use and abuse, and other mental health complications.

But as physicians and scientists, we also had to question – was it more than just the social adjustments we had to make? After all, the virus often announced itself by the loss of smell and taste. Did not the olfactory nerves provide a direct conduit to the brain? Some infected people complained of brain fog, and a few developed full-blown encephalitis. Might our brains be infected and respond in different ways? In some of us, could the virus have settled in just the right cells to make us anxious or depressed? Reports emerged that all sorts of neuropsychiatric disorders were increased following COVID-19. Could the virus trigger anxiety and depression as well?

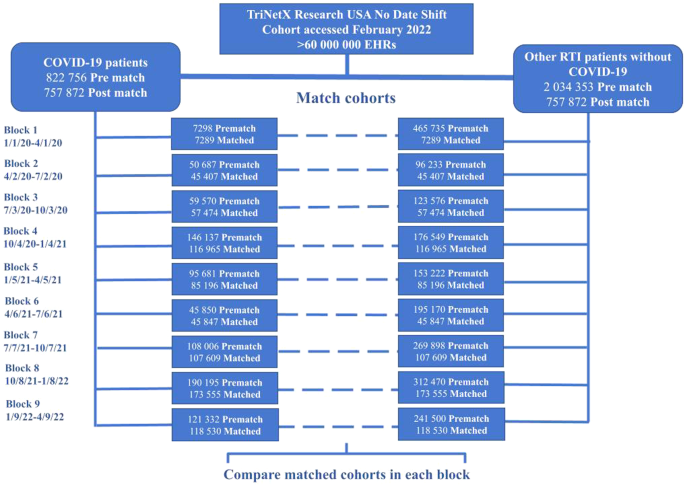

We tackled this question with an active multitalented group of investigators – an AI maven, an expert in analytics, Rong Xu, PhD; an experienced physician-researcher, Pamela Davis MD PhD; a bioinformatics expert David Kaelber MD, PhD MPH; an epidemiologist experienced in infectious outbreaks, Pauline Terebuh, MD, MPH; and a bevy of medical students at Case Western Reserve University School of Medicine eager to understand the full implications of the pandemic and extraordinarily collaborative with one another. One of these bright and capable  med students, Christina Wang (left) , focused on the secular trends in new diagnoses of anxiety and depression. We had access to the TriNetX Analytics Platform due to the participation of our teaching hospital MetroHealth System and its CMIO David Kaelber, MD, PhD, MPH. TriNetX is a nationwide database of over 100 million deidentified electronic health records, from which we could build patient cohorts and conduct statistical analyses with its built-in analytics. We examined new diagnoses of anxiety and depression in three-month blocks from the start of the pandemic in patients who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 and compared them to patients who had had other respiratory illnesses, but not COVID, or who had broken a bone in the same time frame.

med students, Christina Wang (left) , focused on the secular trends in new diagnoses of anxiety and depression. We had access to the TriNetX Analytics Platform due to the participation of our teaching hospital MetroHealth System and its CMIO David Kaelber, MD, PhD, MPH. TriNetX is a nationwide database of over 100 million deidentified electronic health records, from which we could build patient cohorts and conduct statistical analyses with its built-in analytics. We examined new diagnoses of anxiety and depression in three-month blocks from the start of the pandemic in patients who had been diagnosed with COVID-19 and compared them to patients who had had other respiratory illnesses, but not COVID, or who had broken a bone in the same time frame.

As the data came rolling out, with this study and another, conducted by MD/MPH student Veronica Olaker, on new diagnoses of alcohol use disorders, we saw that the first three months of the pandemic indeed had many more new diagnoses among the COVID-19 survivors than among either control group. This was, pretty much, what we all guessed. However, after that first three-month period, new diagnoses of anxiety and depression were like controls - until the Delta wave hit. After months of declining infection, the enemy had shape-shifted, and we were once again afraid. But soon that small wave subsided, and anxiety and depression returned to a pattern like that of other persons who had a medical encounter during that time. Veronica Olaker found the same temporal pattern for new diagnoses of alcohol use disorders – highest at the beginning of the pandemic, then falling, with a small rise during the Delta wave, and then falling again.

To be sure we were not somehow misled by pandemic diagnostic inaccuracies, Christina Wang, assisted by Rhea Kohli, also studied new prescriptions for anxiolytics and anti-depressant medications. They followed a similar temporal pattern. So did diagnoses of recurrent depressive disorder. Same pattern for repeat prescriptions for anti-depressants. It seemed that it was the people’s responses to pandemic stress that produced anxiety and depression, more so than the virus itself.

Although the hoopla in the press was about the rise in anxiety and depression in young people, our results indicated that actual diagnoses of anxiety or depressive disorders occurred at higher frequency in those over 65 years of age throughout the pandemic. The elderly bore the brunt of severe COVID disease and death during the pandemic, and the survivors were more likely to have lost a spouse or a close friend than younger people. Unfortunately, even with our very large data set, we did not have sufficient numbers to test whether women of childbearing or “sandwich” generation age would also be more vulnerable, as we suspected.

Of course, an observational and retrospective study like ours can never rule out completely a direct effect of the virus or some combination of factors, as it only identifies association, not causation. But it seems to be how we respond, not how the virus attacks us, that gives rise to severe anxiety and depression. This temporal pattern goes along with other data in the literature on human response to massive environmental stressors – after the initial upheaval we settle back into a more accepting mode. It teaches us a little bit more about our own humanity.

- Pamela Davis, Christina Wang, Pauline Terebuh , and Rong Xu

Follow the Topic

-

Molecular Psychiatry

This journal publishes work aimed at elucidating biological mechanisms underlying psychiatric disorders and their treatment, with emphasis on studies at the interface of pre-clinical and clinical research.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in