In-memory mechanical computing

Published in Physics

Mechanical computing, overshadowed by electronic computing for about 100 years, has resurged in recent years because it provides a sensing-computing-actuating integrative deformation controlling strategy that facilitates the development of mechanical matter with embedded intelligence. However, data exchange between the mechanical memory and computing modules faces the challenge of inefficient mechanical signal propagation. Here, an in-memory mechanical computing architecture is proposed to address the issue by minimizing the “distance” between computing and data.

The in-memory mechanical computing architecture aims at satisfying the requirement of being framed by distributed, non-volatile, robust, readable, initializable, and reprogrammable mechanical memory units, similar to its electronic counterpart1. Additionally, the interactions between memory units should form function-complete logic sets to ensure the realization of a variety of algorithms, and these interactions should be compatible with the basic neuromorphic computing models to facilitate artificial intelligence.

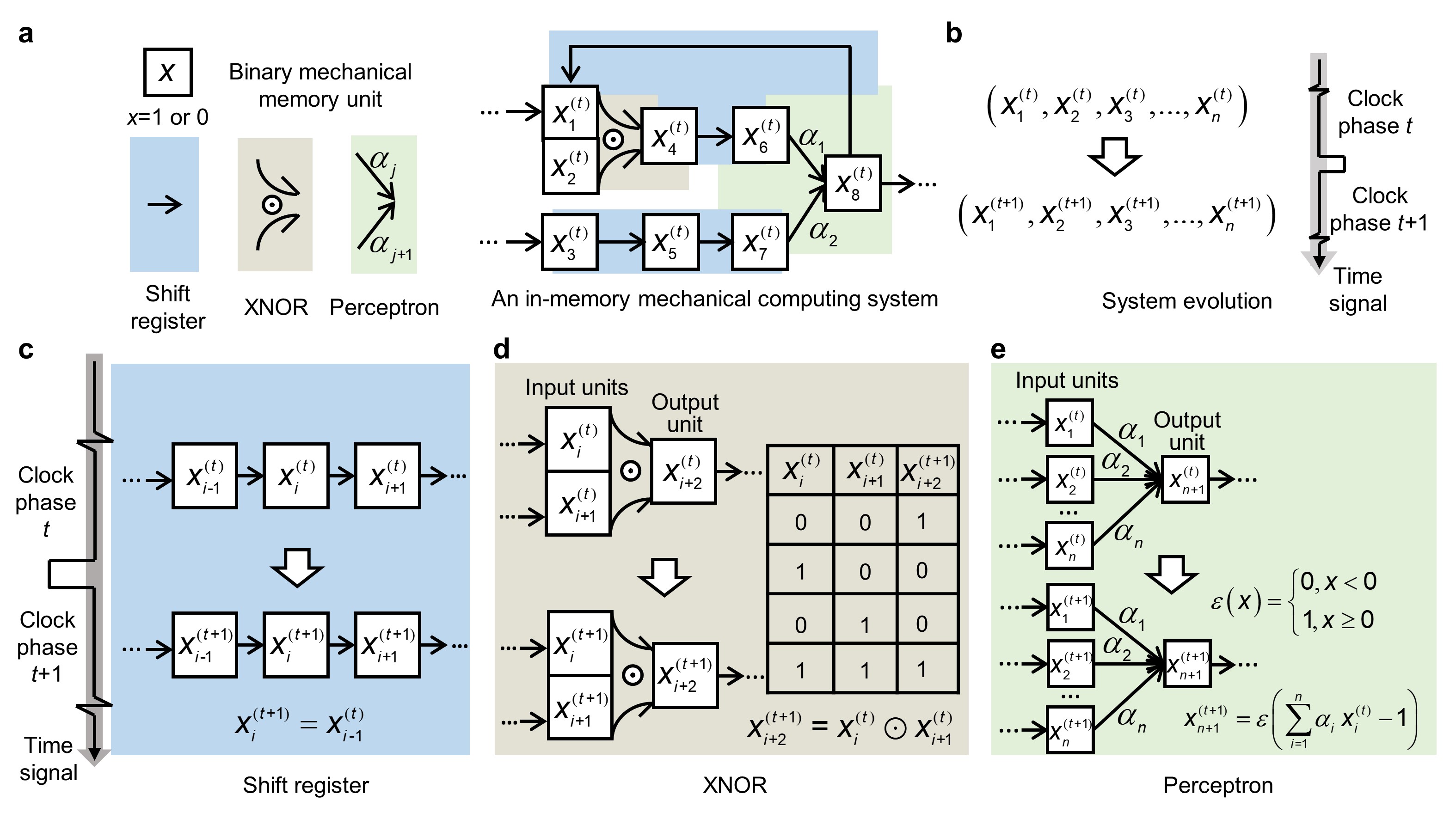

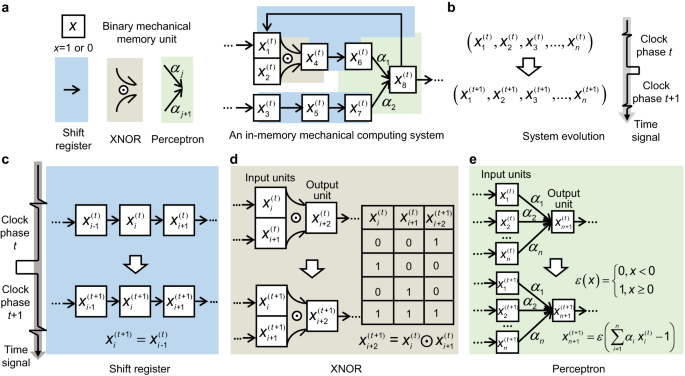

To meet the three requirements, our architecture uses a network of non-volatile binary mechanical memory units (buckled beams represented as the square blocks in Fig. 1a) that can be reprogrammed and initialized by an external force. The blocks have three basic interaction operations: a shift register (black arrows), an XNOR gate (curved arrows and plus the odot symbol), and perceptron operations (arrows with weight parameters). The state of the system at clock phase t is described by all memory units. Driven by a time signal (Fig. 1b), the system evolves to another state as simultaneous data writing, data reading, and computation occur in the mechanical memory unit array according to the organization of interaction networks.

Fig. 1 Schematic of an in-memory mechanical computing system. a An in-memory mechanical computing system consisting of binary mechanical memory units and their interactions (i.e., shifter register, XNOR, and perceptron operations). b Its computing process as the state evolution of the memory units. c Interaction serving as a shifter register. d Interaction serving as an XNOR gate, together with its truth table. e Interaction serving as a perceptron operation.

With the mechanical shift register (Fig. 1c), data with different clock phases can be written into the mechanical memory units in a tandem array to participate in computation together. Thus, the historical data influence subsequent decision-making in the mechanical system, which is a foundation of learning. For the XNOR operation (Fig. 1d), It can differentiate two binary data, which is beneficial for error analyses and for adaptation of the mechanical computing system. For the perceptron operation (Fig. 1e), it is a variant version of the McCulloch-Pitts artificial neuron model, enabling a mechanical system with embedded neuromorphic arithmetic. Note that the XNOR and perceptron operations can provide a function-complete logic space for the proposed architecture.

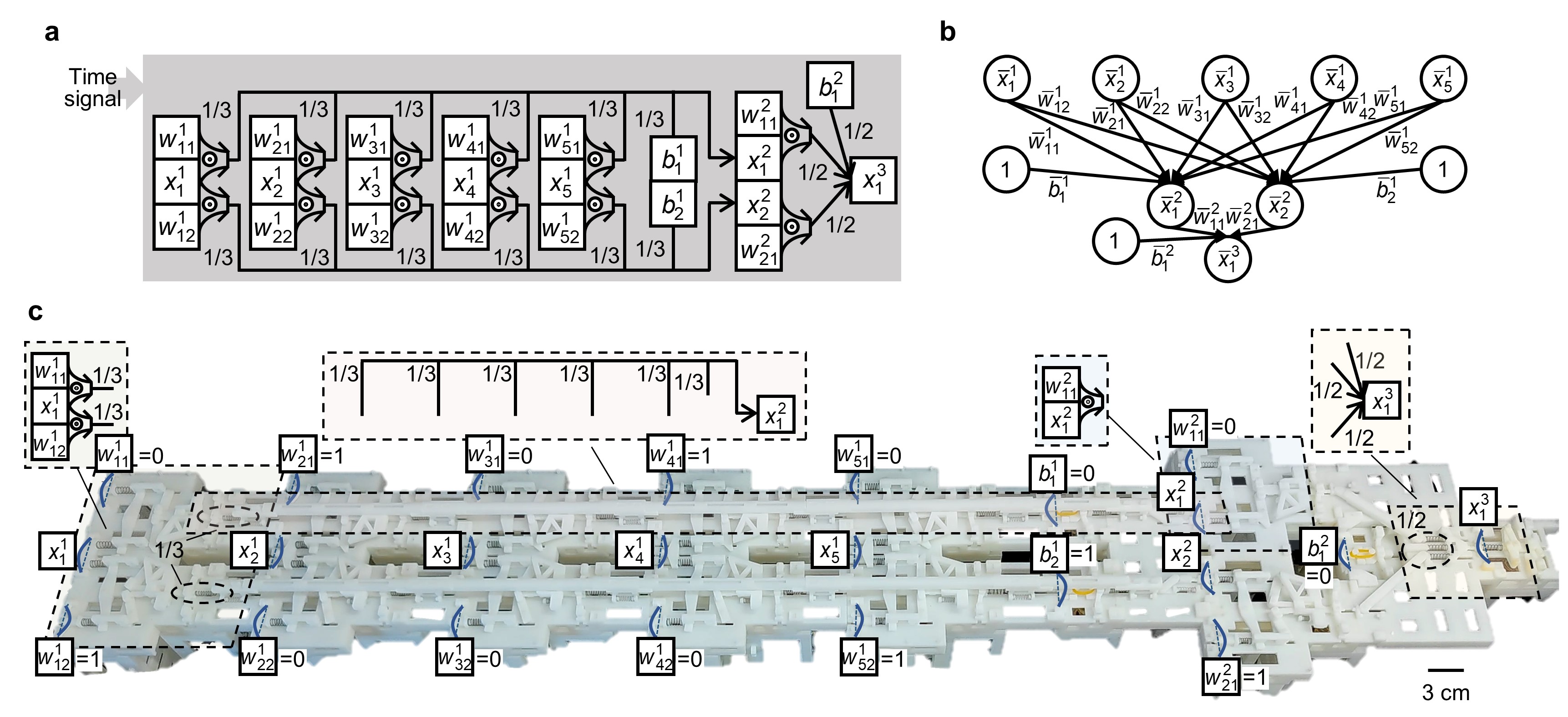

Fig. 2 Mechanical binary neural network. a A mechanical binary neural network with an input, a hidden, and an output layer. b An equivalent binary neural network of a. c The mechanical binary neural network in the experiment.

The MBNN (Fig. 2a) can execute the same function as a trained binary neural network (Fig. 2b). This is done by ensuring that the weights and biases of the MBNN are chosen so that mechanical memory units yield 0 or 1 when the corresponding trained BNN would yield -1 or 1. We have trained a BNN that can judge the parity of input Morse code numbers 0–9. The corresponding MBNN in the experiment is given in Fig. 2c, where the values of the weight and bias are marked.

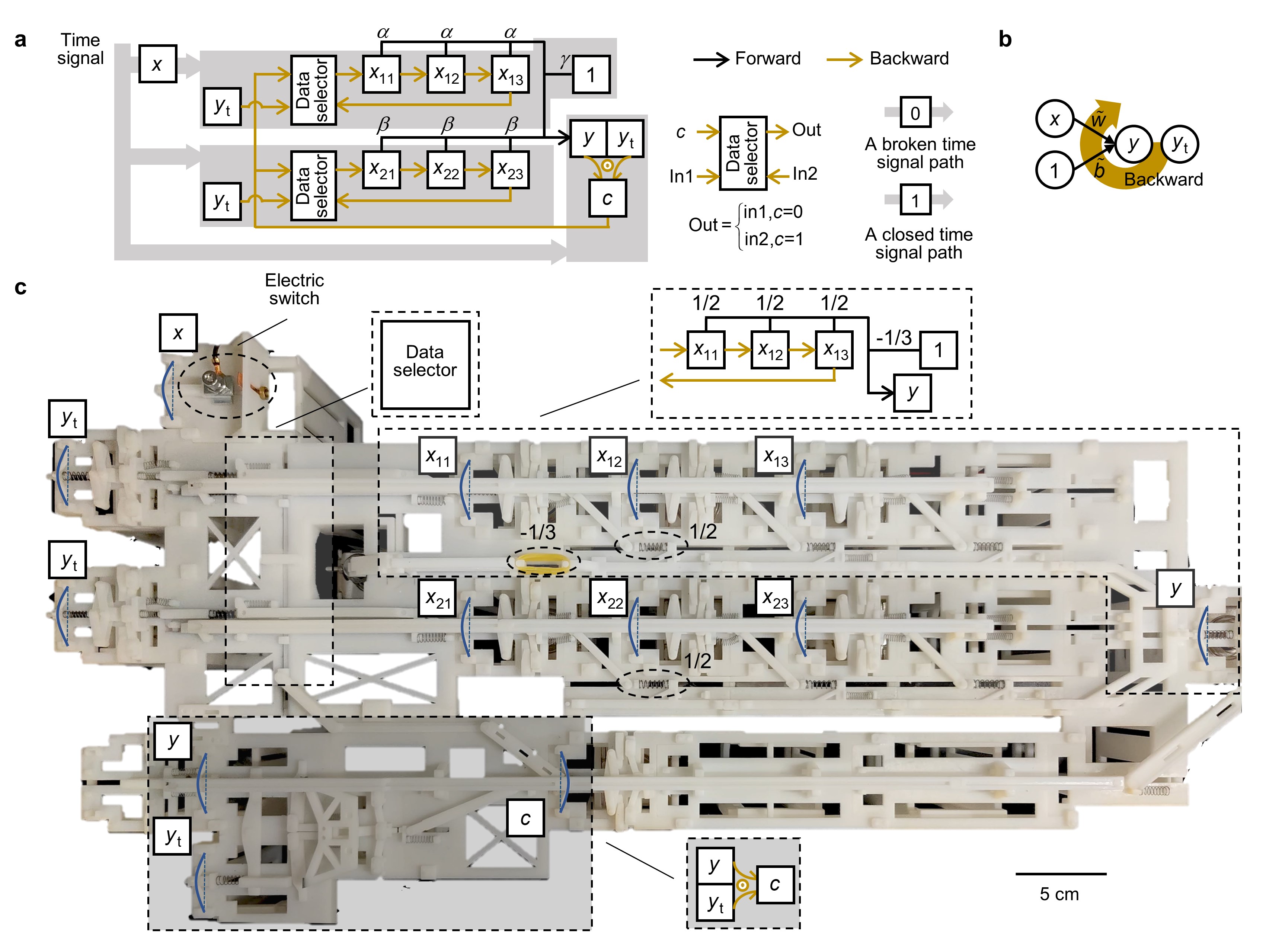

As for the mechanical self-learning perceptron model, it has a forward propagation procedure represented in Fig. 3a (black interaction symbols). The forward procedure of the mechanical self-learning perceptron matches that of the Rosenblatt perceptron (Fig. 3b). Furthermore, the backward propagation procedure of the mechanical self-learning perceptron is represented by the interaction symbols in brown in Fig. 3a. Once the corresponding mechanical memory units receive the time signal, they evolve according to the result c of XNOR under the control of the data selector. A fully functional mechanical self-learning perceptron was 3D printed and demonstrated (Fig. 3c). The functions of some typical components are marked. The mechanical self-learning perceptron can acquire target input-output relationships under a supervised learning manner.

The coordination between distributed data read-write interfaces and the computing process of the in-memory computing architecture may be beneficial for adaptive and intelligent deformation control. The absence of long-range data transfer is promising for neuromorphic decision-making and biomimetic self-learning mechanical systems. Applications of the proposed computing architecture could include robotics with neuromorphic operations in extreme environments where electronics may not be suitable. In general, the in-memory mechanical computing architecture can serve as an intelligent mechanical skeleton for embedding microelectronic devices, benefitting the construction of intelligent robotics and metamaterials2,3.

References

- Di Ventra, M. & Pershin, Y. V. The parallel approach. Nature Phys 9, 200–202 (2013).

- Meng, Z. et al. Encoding and storage of information in mechanical metamaterials. Advanced Science 10, 2301581 (2023).

- Mei, T., Meng, Z., Zhao, K. & Chen, C. Q. A mechanical metamaterial with reprogrammable logical functions. Nat Commun 12, 7234 (2021).

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in