Learning how to exploit bacterial competition to target harmful strains

Published in Ecology & Evolution and Microbiology

The problem with using antibiotics

In recent years, we now know how important microbiomes are to our health and the environment. The community of microbes inside our intestinal tract, the gut microbiome, is a prime example. However, microbiomes can also contain harmful bacteria like pathogens or antimicrobial resistant strains. One strategy to get rid of these harmful bacteria is to use antibiotics. This can work well, but it is not always guaranteed that the strain you want to target is sensitive to the chosen antibiotic, particularly as antibiotic resistance becomes more common. The other issue with using antibiotics is that it often hits the rest of the microbiome as collateral damage, which is a problem given how much we benefit from our microbiomes.

What can we do? Well, the dream scenario would be to be able to target a specific strain, while leaving the rest of the microbiome intact. Sounds challenging, right? Well, it is! There’s been a lot of exciting work to try and achieve this goal using various approaches, but we are far from having a clear route forward to replace antibiotics.

Our approach

When we were thinking about this problem, we got inspired by some long-term studies in human participants that tracked the composition of the gut microbiome over time from stool samples. Those studies found that dominant strains within a species like Escherichia coli change over time. Therefore, we decided to look at how bacteria natural live and compete and see if we could find clues there about what causes turnover.

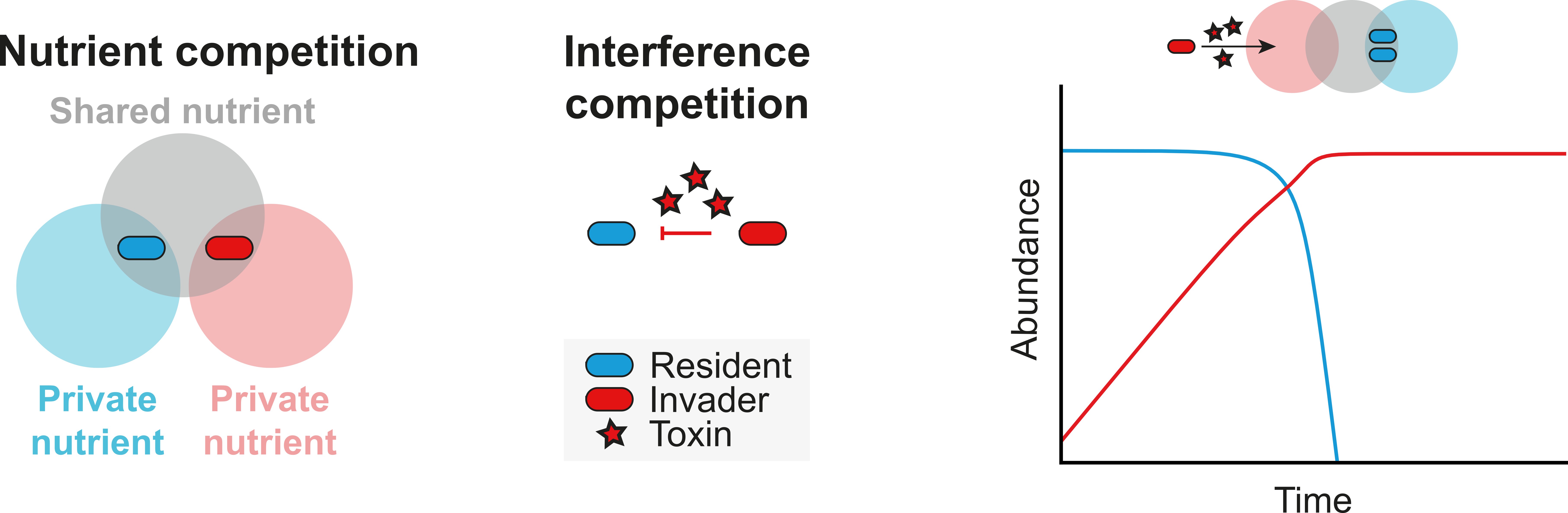

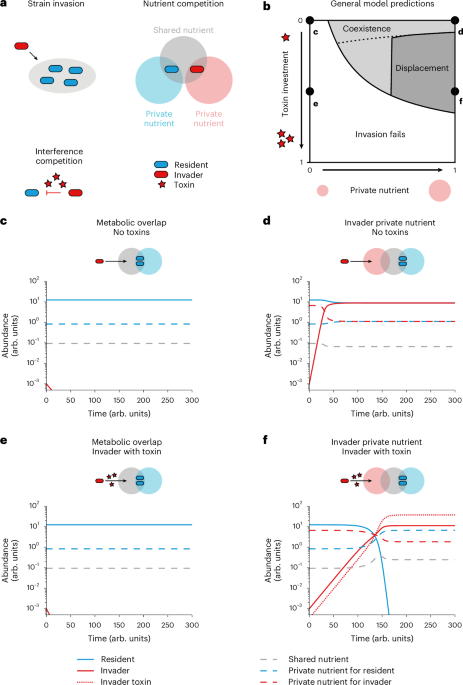

Bacteria compete in two main ways. They can compete direct for priority access to a given resource over their competitors, called resource competition, for example by evolving dedicated metabolic pathways. They can also directly kill their competitors using an impressively diverse arsenal of “bacterial weapons” such as toxins or molecular spears. This form of competition is called interference competition. There has been quite a bit of work on each of these form separately, but surprisingly little work investigating both forms of competition at the same time. We then thought that if we figured out how these two forms of competition worked together, we might be able to repurpose this for our own advantage.

Learning math: Making a complicated problem slightly less complicated

Coming up with a strategy to investigate two forms of competition in all combinations seemed like a challenging task, especially when embedded in the context of a diverse microbial community. Given the experimental background of the postdoctoral researcher leading the project, the first instinct was to prepare a massive-scale experiment in the lab. Just as media was getting ready to be placed in the autoclave and a series of complicated genetic engineering steps were being planned, a foreign piece of advice came from a colleague, Jacob Palmer: “Seems like something a model could explore.”

This comment changed the approach to putting down the pipettes and opening MATLAB. After fumbling through unnecessarily complicated code and revisiting how to set up differential equations for the first time since undergraduate mathematics, the first few intuitions started to materialize: it seemed like bacterial warfare was never effective for an invading strain coming into a microbiome unless it had an available nutrient leftover from the resident community it could use to grow. The modeling also showed that if a strain can invade using available nutrients, it could now use bacterial warfare too kill a pre-established resident strain (Fig. 1). This was exciting for two reasons: 1) it showed that there is a powerful interaction between both forms of competition, and 2) it showed the postdoctoral researcher the power of mathematical modeling. But before getting too excited, we asked another member of our team, a PhD student trained in mathematics to re-run the analysis to be sure. Not only were they able to confirm the results, but they were also able to generalize our first results and establish a formal theoretical framework for how strains use ecological competition to first invade and then displace other strains in a community.

Figure 1: If an incoming strain has access to nutrients leftover by the community, it can invade and kill an existing strain if it also encodes bacterial weapons such as a toxin.

Back to the lab: Our models were useful!

Now, it came time to test our predictions. We set up a series of simple experimental tests using E. coli to confirm the relationship between nutrient competition and interference competition. Not only could we verify our modeling results, but we showed that we could engineer strains of E. coli to actively target harmful antimicrobial resistant isolates of E. coli from within a microbial community using these principles.

To do this, we checked the nutrient utilization profile of all strains within a community, and compared that to an incoming strain that we engineered to encode a bacterial weapon. All we had to do was then supplement a nutrient into a community that only the engineered invading strain could use. Then, just like the models (Fig. 1), we could reduce the abundance of the target antimicrobial resistant isolate, dependent on the bacterial weapon, and keep the rest of the community intact.

How might we use ecological competition to target harmful strains in practice?

Our work suggests that if you know which nutrients a microbial community can use, you could potentially engineer a microbiome in a very specific way. There are clearly a lot of challenges here, but it lays the beginning of exciting future work. While it might not be easy to find available nutrients to introduce a new species in an existing microbiome, things could change under conditions where a microbiome is disrupted, providing a window of opportunity for community engineering. Additionally, we could try to engineer microbes to utilize rare or synthetic nutrientsthat we could supplement to microbiomes, such as in the diet for the gut microbiome. Clearly, we need a better understanding of how microbes use different nutrients, and the effect of metabolism on community composition. This inspired us to write a review about this very topic (https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chom.2025.05.013).

But importantly, our work shows that it is worth keeping an open mind and potentially learning new approaches, in this case mathematical modeling, to help address challenging questions.

Link to paper in Nature Microbiology: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41564-025-02162-w

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Biotechnology

A monthly journal covering the science and business of biotechnology, with new concepts in technology/methodology of relevance to the biological, biomedical, agricultural and environmental sciences.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in