Mountain wildlife and the costs of living dangerously

Published in Earth & Environment, Ecology & Evolution, and Zoology & Veterinary Science

Snow is a major, climate-sensitive feature of the Earth’s surface and catalyst of fundamentally important ecosystem processes. Understanding how snow influences sentinel species in rapidly changing mountain ecosystems is critical. Previous study has focused on ecologically-oriented effects of snow on food availability, energy expenditure, and predation however the physical process of avalanching snow may likewise exert major impacts. To understand the ecological implications of snow avalanches, we implemented a multidisciplinary study bridging long-term wildlife ecology field data and innovative snow science remote sensing modeling techniques. The goal: to detail a previously undescribed pathway by which snow alters demographic processes of mountain wildlife.

Famously described as "a climbing bearded beast the color of winter", mountain goats are an iconic species of North American mountain cultures and landscapes. A species of alpine ungulate belonging to a taxonomic group comprising 32 mountain dwelling species in 70 countries, mountain goats are specially adapted to life in steep, rugged terrain. Their use of cliffs as refugia is an effective counter to the risk of predation by wolves and other large carnivores but poses other dangers. During winter, snow avalanches are widespread in steep, mountain terrain and may exert significant risk to alpine species. A factor that may be especially pernicious because avalanche risk can be largely imperceptible with the unstable layers that trigger slides being buried deep within the snowpack.

To what extent do mountain ungulates die in avalanches? And, why? What are the implications for a climate-sensitive species that commonly occurs in small, isolated and vulnerable populations?

To address these knowledge gaps, we conducted a long-term study of mountain goat demography in the snowy, avalanche-prone Coast Mountains of Alaska. We captured and satellite radio-collared over 400 mountain goats in four study areas, carefully monitoring their movement patterns and fates over a 17-year period. When animals died, we conducted aerial reconnaissance and follow-up ground examinations to determine cause of death. We determined that 36% of all mortalities, on average, were caused by avalanches but that patterns varied spatially. In the most avalanche prone areas, over 60% of mortalities were caused by avalanches. Translated into direct demographic impacts, we determined that 8% of individuals in a population died due to avalanches annually, on average, but in the “worst case scenario” up to 22% of a population could be killed by avalanches.

The implications of avalanche mortalities for often small, isolated mountain goat populations can be profound. Mountain goats have low reproductive rates and a slow life-history strategy, leading to heightened sensitivity to population perturbations. Documented growth rates, for instance, typically range between 1-4% suggesting high levels of avalanche mortality exert substantial negative impacts on population trajectories. Unlike other causes of death such as predation and malnutrition that selectively remove immature and old animals from the population, avalanches were found to kill animals at random. As a result, avalanche mortalities included a significant fraction of prime-aged mountain goats of high reproductive value and likely exacerbate impacts on populations.

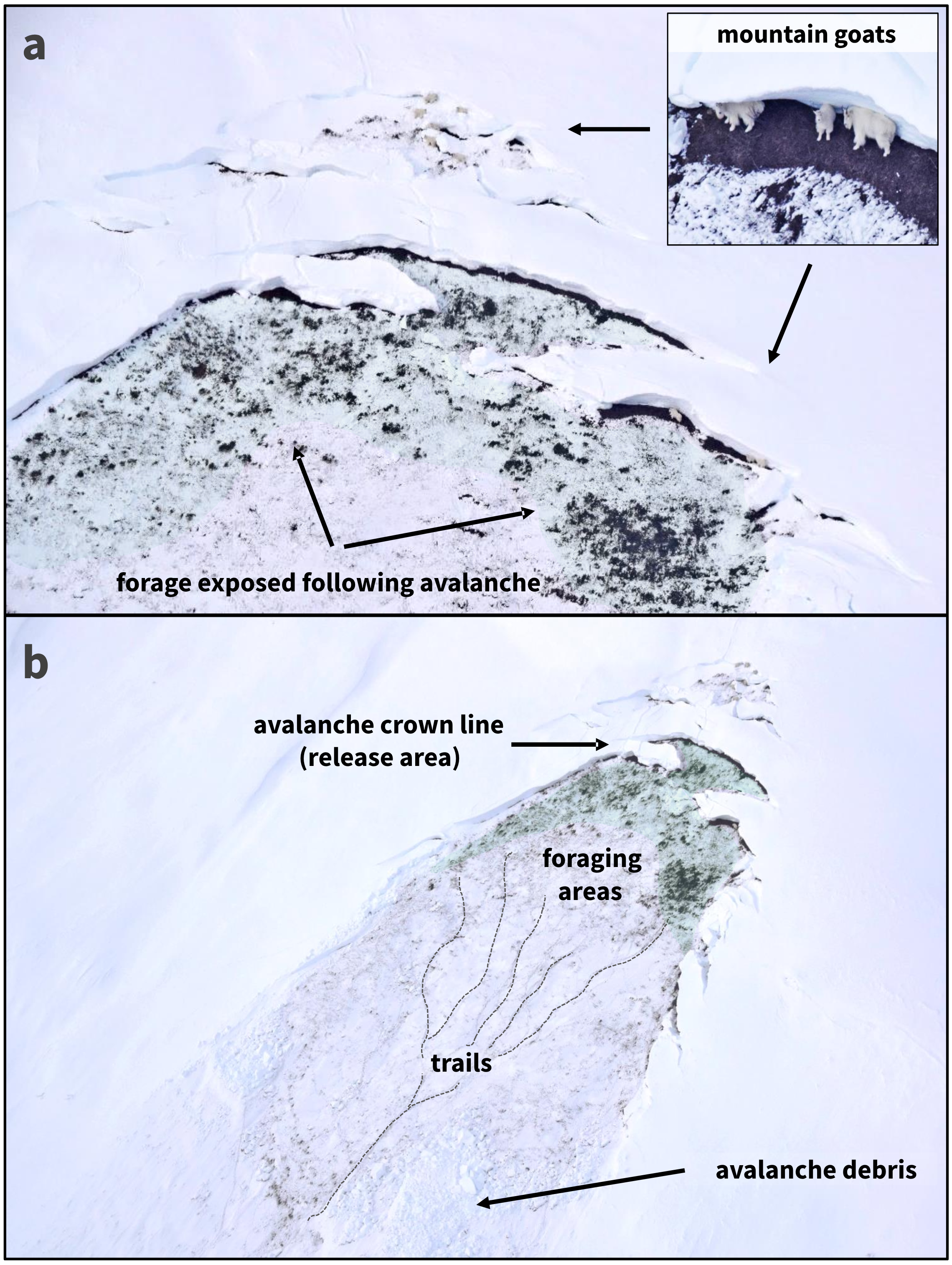

To understand why mountain goats die in avalanches, we combined mountain goat GPS radio-collar location data with innovative avalanche hazard simulation modeling. Our analyses revealed that individual animals that died in avalanches spent more time in risky avalanche terrain as compared to those that did not die. Further, our results indicated that avalanches deaths occurred across nine months of the year but were most common during early- and late-winter periods when snowpacks were less stable. While mountain goats may reduce risk of predation by using steep, avalanche prone terrain benefits may have nutritional underpinnings as well. For example, avalanches can provide important mid-winter sustenance when slides expose vegetation, and in spring, when early-emerging “green waves” of nutritious forage appear in avalanche chutes recently swept clean of snow. Our earlier reported high rates of avalanche mortality suggest that the benefits of utilizing avalanche terrain may offer corresponding high fitness payoffs for populations to offset negative impacts and maintain persistence.

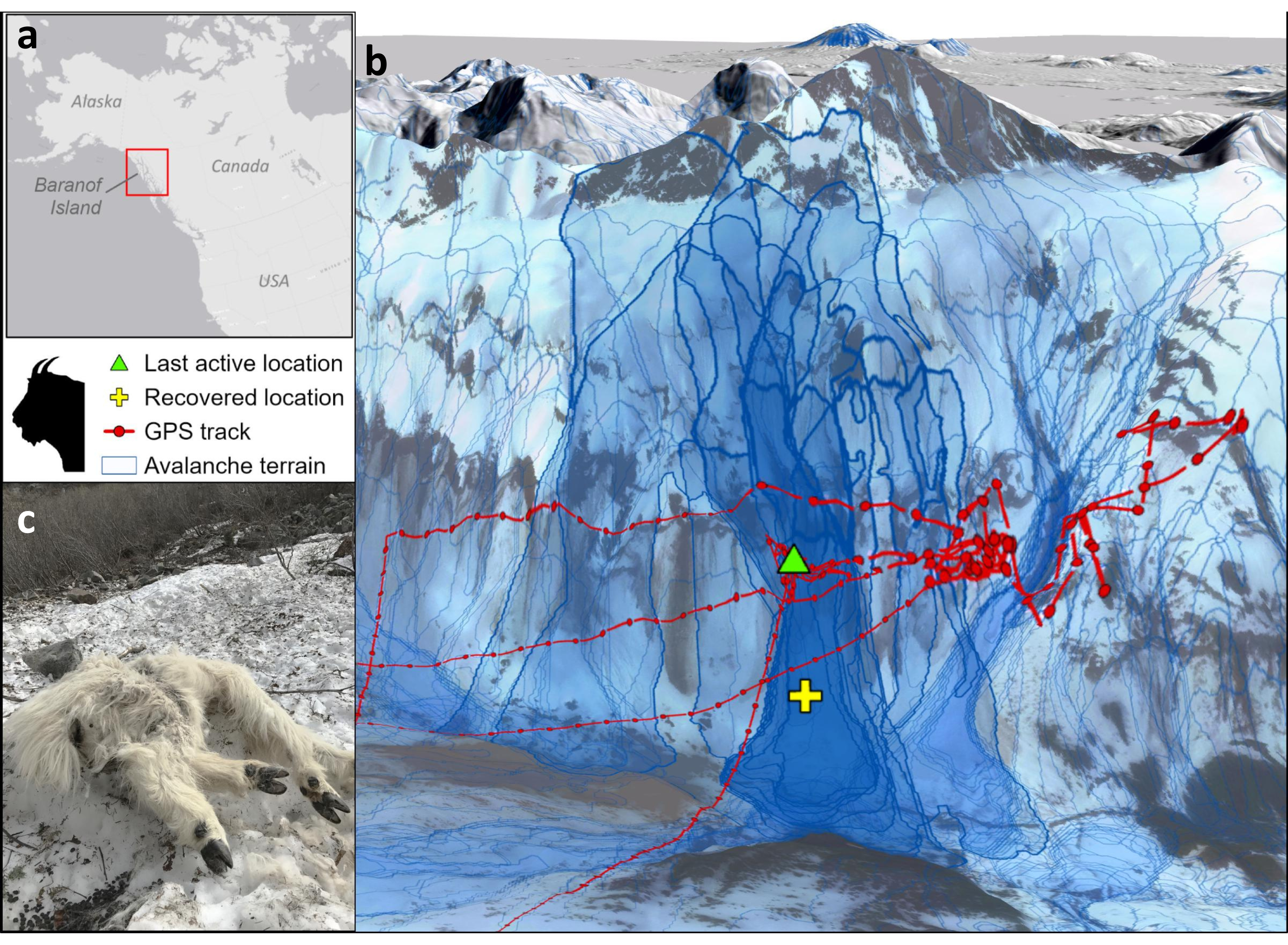

Estimation of mountain goat use of avalanche terrain. (a) Mountain goat study location where (b) GPS radio-collar location data were intersected with large-scale avalanche hazard indication maps to quantify individual mountain goat exposure to avalanches. The example 3D image illustrates typical winter use of avalanche terrain by an adult female mountain goat (BG041) that was caught (triangle) and subsequently buried (cross) by an avalanche in the Baranof Island study area in January 2016. Simulated avalanches that swept through the mountain goat mortality site are delineated (thick blue outlines), as well as all other avalanches in the area (light blue outlines). (c) A mountain goat (KG034) carcass partially buried in avalanche debris, near Klukwan, Alaska in May 2017. The animal suffered a depressed skull fracture among other critical injuries.

An ice age relic of modern-day Pleistocene landscapes, mountain goats are sentinels of change in alpine ecosystems and particularly sensitive to shifts in weather and climate. How climate change is likely to alter the prevalence of avalanches, and their influence on this species is an important area of future research. Existing evidence suggests changes will vary geographically and track projected increases in extreme weather events. How these dynamics play out in a future marked by climate change across the diverse range of mountain goats, and other alpine species, will have important implications for future viability and resilience.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Biology

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary in all areas of the biological sciences, representing significant advances and bringing new biological insight to a specialized area of research.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Signalling Pathways of Innate Immunity

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Feb 28, 2026

Forces in Cell Biology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Apr 30, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in