Of kings and Alpine ibex: the amazing resurrection of a species from near-extinction

Published in Ecology & Evolution

The story begins with the steady and devastating decline of Alpine ibex during medieval times. Locals could easily hunt ibex because the animals tend to show little fear and search refuge in steep terrain instead of fleeing. The decimation brought the species to near extinction in the 19th century. The contemporary Italian king Vittorio Emmanuelle II enjoyed the Alpine ibex hunt very much himself. Facing declining populations, he decided to establish a game park protected by locals. But instead of protecting Alpine ibex, the park served as a protected ground for the king's yearly summer hunting trips. In the 19th century, Alpine ibex were eradicated across the Alps and the king's protected hunting ground became the sole surviving population. The king killed many thousand individuals and decorated his hunting castle with the collected horns. Yet, he just did not manage to kill them all.

At the dawn of the 20th century, two ingenious Swiss with the help of an Italian poacher sneaked into the park and smuggled three younglings over the border to Switzerland. The animals reproduced well in local zoos and soon more individuals were smuggled across the border. In 1911, the first population was reintroduced in the Swiss Alps, followed by many more. Careful planning dictated a very specific reintroduction scheme, with individuals from certain well-established populations being translocated to not yet populated areas. The consequences are not only that the species survived but that Alpine ibex represent one of the best documented, successful species reintroductions.

The park still exists and is now known as the Parco Nazionale Gran Paradiso. More background on the reintroduction of Alpine ibex can be found here.

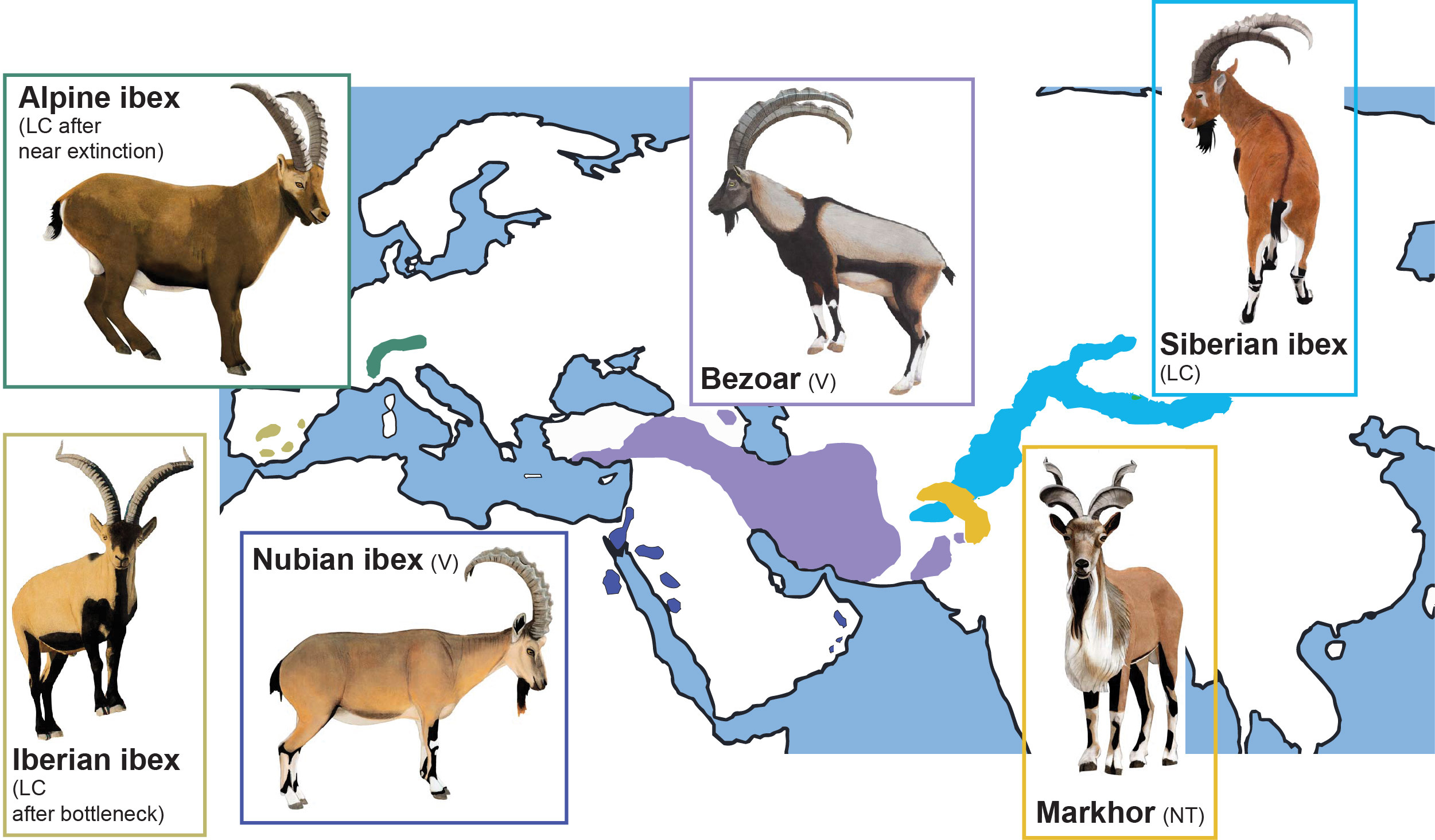

In our paper, just published in Nature Communications, we studied Alpine ibex populations for signatures of their recolonization history. We analyzed an extensive dataset of 60 genome sequences of Alpine ibex and six closely related species. Alpine ibex are currently considered Least Concern by the IUCN. Yet, we found an accumulation of deleterious mutations compared to species that have not suffered such a severe bottleneck. A significant mutation burden may impact a species in the long run. Should the census-size based IUCN assessments be expanded to include genetic risk factors where known?

Next, we asked whether the step-wise population reintroductions across the Alps had an impact on the mutational burden. Small populations should have less efficient purifying selection acting against deleterious mutations. Hence, a bottleneck could lead to an increase in deleterious mutations. There is a competing force at play though. Small populations tend also to show more inbreeding (mating between related individuals). Inbreeding leads to higher homozygosity (twice the same copy of a gene variant) and deleterious mutations are also more likely to be at a homozygous state. The most deleterious mutations are often recessive (i.e. their negative effect is only seen when homozygous). Hence, a strong bottleneck can expose highly deleterious mutations to selection. This process is called purging. Theory predicts under what conditions purging should occur, however we largely lack empirical evidence in wild populations.

Given the detailed historic records, we knew very well which populations were established from which source population. We also had good estimates of historic population sizes in the 20th century. Hence, we tested whether small population size was associated with the purging of highly deleterious mutations. We found indeed results consistent with purging meaning that the most bottlenecked populations had reduced levels of highly deleterious mutations. But despite the purging of some highly deleterious mutations, the accumulation of a large number of mildly deleterious mutations led to an overall higher mutation burden.

Our study highlights that even successfully reintroduced species may carry forward genetic risks. We suggest that to ensure the long-term survival of a species, at least ~1000 individuals should be preserved. This makes conservation efforts aimed at the thousands of critically endangered species even more pressing.

Reference

Grossen C, Guillaume F, Keller LF, Croll D. 2020. Purging of highly deleterious mutations through severe bottlenecks in ibex. Nature Communications. DOI: 10.1038/s41467-020-14803-1

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in