On the sources of lithium-rich granites and pegmatites

Published in Earth & Environment

Lithium is classified as a critical metal due to its rising demand for modern-day technologies, such as batteries for vehicles and electronics. Critical metals are crucial for a sustainable energy transition; therefore, it is imperative to discover and exploit new mineral resources. Lithium is primarily sourced from “hard-rock” deposits, namely granitic pegmatites, which account for approximately 60% of the global lithium supply [1]. Since their discovery, pegmatites have fascinated and perplexed geologists due to their peculiar geochemical and textural characteristics. Most notably, pegmatites are renowned for their plurimetric crystals, high purity quartz and feldspars, gem quality minerals, and the potential for the mineralisation of rare elements, such as lithium [2]. Despite the economic significance of rare-element pegmatites, the genetic mechanism of these “geochemical anomalies” has been debated by the scientific community for over a century. In order to improve exploration prospects for granite-related ore deposits, it is important to better understand how and where they form in the Earth’s crust.

Lithium mineralisation in the Chédeville Pegmatite at Monts d’Ambazac, Massif Central (France). Lithium is primarily hosted in lepidolite, which gives the rock its distinct purple colour. © BRGM – Éric Gloaguen

Scientific debates regarding the origin of granitic rocks dates back to the 18th century. On one hand, the “Neptunists” believed that granites precipitated from an early ocean, thus having a sedimentary source [3]. This theory was succeeded and refuted by the “Plutonists”, who demonstrated that granites crystallise from a parental magma and thus have an igneous origin [3]. Although the neptunist versus plutonist debate has long been settled in the scientific community, its relevance for the formation of rare-element pegmatites remains timely. The genesis of rare-element pegmatites has been historically associated with the extraction of residual melts from highly crystallised parental granites (igneous source) [4]. However, a limitation of this genetic model is that pegmatites are often isolated, without a clear spatial or temporal relationship to a parental granite [5]. This lead researches to speculate that lithium-rich melts may be sourced from deeper in the crust by the partial melting (anatexis) of metasedimentary rocks (sedimentary or anatectic source) [5].

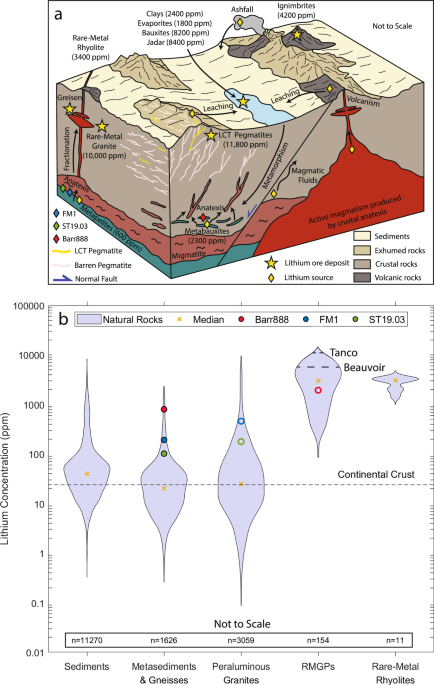

The cycling of lithium in the crust between different crustal reservoirs, modified from Gloaguen et al. [6] and Lefebvre and Tavignot [7]. Rare-metal granites and lithium-caesium-tantalum (LCT) pegmatites may form by the anatexis of metasedimentary rocks (e.g., metapelites or metabauxites) or by the fractional crystallisation of granitic melts.

However, the crustal rocks that may source rare-element pegmatites often remain enigmatic as they are situated several kilometres deep in the crust in relation to ore deposits. Experimental petrology can be a powerful, albeit challenging tool for geologists, which can be used to simulate crustal processes such as melting and crystallisation in the laboratory. Here, we used an experimental approach to test whether rare-element pegmatites can form by the anatexis of crustal rocks. We performed partial melting experiments on variably enriched metasedimentary rocks, wherein lithium is primarily hosted in a metamorphic mineral called staurolite. We postulated that the partial melting of lithium-rich, staurolite-bearing metasedimentary rocks may produce melts that are comparable in composition to rare-element pegmatites.

The anatexis of conventional metasedimentary rocks formed melts that are depleted in lithium by over an order of magnitude relative to rare-element pegmatites. In contrast, the partial melts produced by the anatexis of enriched crustal rocks are similar in composition to some rare-element pegmatites; however, they are depleted in lithium relative to economic-grade deposits. Therefore, the produced melts must get extracted and become further enriched in lithium during fractional crystallisation to produce economically important rare-element pegmatites.

We conclude that lithium enrichment in granites and pegmatites begins with the anatexis of an enriched crustal source. We ponder on the merits and caveats of variable crustal rocks (metabauxites, metapelites, gneisses, and metavolcanic rocks) being the sources of rare-element pegmatites. Lithium-rich metasedimentary rocks are poorly explored in nature; therefore, it is imperative to improve exploration prospects for such deposits to better constrain the origin and hence the occurrence of rare-element pegmatites.

I would like to dedicate this paper to my PhD co-supervisor, Éric Gloaguen, who sadly passed away before the publication of our manuscript. The concept for this study was born from the notion of Éric, long before the start of my PhD. Éric was adamant about the anatectic origin of rare-element pegmatites. He firmly believed that the anatexis of staurolite-bearing metasedimentary rocks is a crucial step to produce lithium-rich granitic melts. To support his anatectic model, Éric used a multidisciplinary approach, backed by two decades of research experience on granite-related ore deposits in Europe. The perpetually insightful comments of Éric have greatly enriched our publication and my understanding of granitic pegmatites. Our field excursions to the barren and wet terranes of the French Massif Central in search for lithium-rich rhyolitic dikes will remain particularly memorable to me.

Fieldwork in the Limousin region of Massif Central, France, in search for lithium-rich rhyolitic dikes with Éric. a) One of the few photos in the field where Éric is (partly) facing in the direction of the camera, instead of the rocks. b) The remarkable outcrop exposure of Limousin often requires the removal of vegetation to reveal the hidden underlying rocks. Images were taken by B. Horányi.

References

[1] Bowell, R. J., Lagos, L., de los Hoyos, C. R. & Declercq, J. Classification and characteristics of natural lithium resources. Elements 16, 259–264 (2020).

[2] London, D. & Kontak, D. J. Granitic pegmatites: Scientific wonders and economic bonanzas. Elements 8, 257-261 (2012).

[3] Master, S. Plutonism versus Neptunism at the southern tip of Africa: the debate on the origin of granites at the Cape, 1776-1844. Earth and Environmental Science Transactionf of the Royal Society of Edinburgh 100, 1-13 (2010).

[4] Černý, P., Blevin, P.L., Cuney, M. & London, D. Granite-related ore deposits in One-Hundredth Anniversary Volume: Economic Geology (eds. Hedenquist, J. W., Thompson, J. F. H., Goldfarb, R. J. & Richards, J. P.) 337–370 (Society of Economic Geologists, 2005).

[5] Müller, A., Romer, R. L. & Pedersen, R.-B. The Sveconorwegian pegmatite province – thousands of pegmatites without parental granites. The Canadian Mineralogist 55, 283-315 (2017).

[6] Gloaguen, É., Melleton, J., Gourcerol, B. & Millot, R. Lithium mineralization, contributions of paleoclimates and orogens in Metallic Resources 2 (ed. Decrée, S.) 1-61 (Wiley-ISTE, 2023).

[7] Lefebvre, G. & Tavignot, D. Le marché du lithium en 2020: enjeux et paradoxes. MineralInfo https://www.mineralinfo.fr/fr/ecomine/marche-du-lithium-2020-enjeux-paradoxes (2020).

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Climate extremes and water-food systems

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: May 31, 2026

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in