Overflow metabolism: Why cells waste nutrients—and why it’s not really waste

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology, Earth & Environment, and Biomedical Research

If you’ve ever wondered why living cells sometimes behave in a seemingly “wasteful” way, you’re not alone. For more than a century, scientists have been intrigued by a puzzling phenomenon known as overflow metabolism. This occurs when cells—whether bacteria, yeast, or even our own human cells—consume nutrients like sugar but do not fully use them for energy production and growth. Instead, they release part of these nutrients back into their surroundings as by-products that appear useless, and sometimes even toxic.

At first glance, this seems inefficient. Why would a cell, which has evolved to maximize survival and growth, throw away valuable fuel in the form of harmful compounds?

In our recent review, Overflow metabolism in bacterial, yeast, and mammalian cells: different names, same game (Gosselin-Monplaisir et al., Molecular Systems Biology, 2025), we revisit this longstanding mystery. We argue that this conserved phenomenon is not a flaw or a weakness. On the contrary, overflow follows universal biological principles that apply across all domains of life. And far from being mere toxic waste, these by-products also play essential roles as nutrients, regulators, and even signaling molecules.

Different names, same game

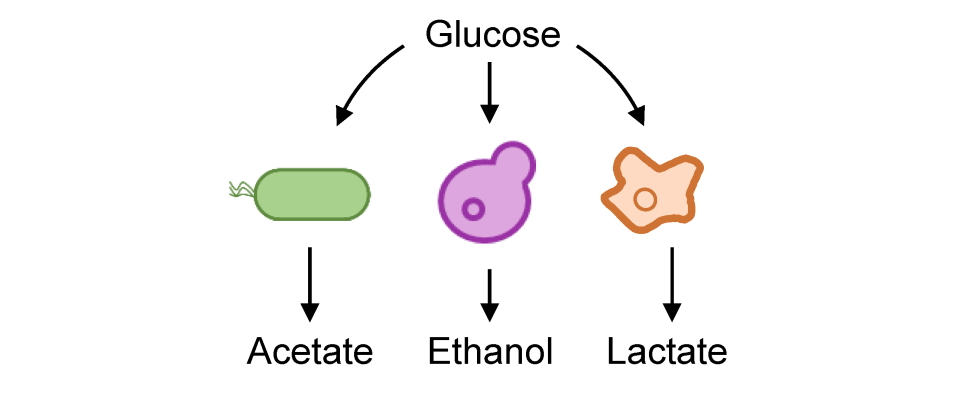

Overflow metabolism has been observed in nearly every organism studied. However, because it has traditionally been investigated separately in different species, scientists gave it different names depending on the organisms:

- In bacteria, such as Escherichia coli, it is often called acetate overflow, where sugar is converted into acetic acid, the same compound found in vinegar.

- In yeast, it is known as the Crabtree effect, where sugar is converted into ethanol—the process behind beer and wine production.

- In mammalian cells, it is referred to as the Warburg effect, where sugar is converted into lactate.

For decades, researchers regarded these processes as distinct curiosities. Our review, however, shows they are actually variations of the same fundamental process, operating in strikingly similar ways across life forms.

Overflow follows universal principles

By analyzing, comparing and integrating studies in bacteria, yeast, and mammalian cells, we identified a set of principles that are conserved across all organisms:

- Reversibility: Overflow is not a one-way street. The molecules cells release (like lactate, acetate, or ethanol) can also be reabsorbed and reused. This makes overflow a reversible process allowing cells to decouple energy production from sugar uptake.

- Shared control: Overflow is not regulated by a single “master switch”, but instead emerges from the interplay between three universal metabolic systems: glycolysis (breaking down sugars), the TCA cycle (burning fuel for energy), and the overflow pathways themselves.

- Thermodynamics: Basic physical constraints force cells to excrete some fuel when sugar uptake is high, at least in absence of by-products. However, when by-product concentrations rise, they push the reaction into reverse, enabling cells to co-utilize alongside sugar what they usually secrete. Overflow metabolites can therefore act as “waste” in some contexts and as “nutrients” in others, depending on sugar availability and environmental conditions.

- Adaptation: Producing overflow metabolites can make cells more resilient to changes in their environment. Acetate helps bacteria cope with fluctuations in sugars availability, ethanol provides yeast with a backup energy source, and lactate allows mammalian cells to share energy between tissues and organs. Far from being only harmful, these molecules also confer benefits to the very cells that produce them.

Taken together, these findings reveal a universal, flexible strategy: evolution has optimized cells not only for efficiency, but also for adaptability, sometimes “wasting” fuel in the short term to secure survival advantages in the long run. This integrated perspective lays the groundwork for a unified theory of overflow metabolism, something biology has long been missing.

Not just toxic waste: Overflow metabolites as beneficial nutrients, regulators, and messengers

One of the most important shifts in perspective is recognizing that overflow products are not simply toxic leftovers.

In bacteria, acetate can help regulate metabolism, maintain carbon balance, coordinate collective behaviors such as biofilm formation, and even promote growth. In yeast, ethanol triggers a global cellular response and provides reducing power to sustain energy demands. In human health, lactate, long blamed for muscle fatigue, is now recognized as both a signaling molecule and a vital fuel shuttled between organs. It also plays key roles in cancer metabolism, immune response, and brain function.

Far from being mere waste, these molecules act as by-products, nutrients, and messengers, enabling cells to communicate and adapt collectively to changing environments. Only by appreciating their context-dependent roles can we fully understand the significance of overflow metabolism.

Why it matters

Understanding overflow isn’t just an academic puzzle—it has real-world implications.

In biotechnology, where microorganisms are harnessed to produce food, fuels, or medicines, the buildup of overflow by-products can reduce efficiency. By applying the principles identified here, we can design smarter bioprocesses that either minimize these by-products or recycle them into valuable compounds.

In healthcare, overflow metabolites are continuously exchanged between our cells, organs, and gut microbiota. When these exchanges are disrupted, the result can be diseases such as cancer, obesity, or microbiome-related disorders. A deeper understanding of overflow could therefore open the door to new diagnostics and therapies.

Final thoughts

What once seemed like a costly flaw now appears to be a clever survival strategy. Overflow is not a defect in cellular design but a universal mechanism that organisms from bacteria to humans use to thrive in a dynamic world.

As we continue to investigate this phenomenon across species, we may discover that the production of “toxic waste” we once tried to suppress is, in fact, a powerful driver of life’s resilience, communication, and adaptation.

Follow the Topic

-

Molecular Systems Biology

Systems biology is an integrative discipline that seeks to explain the properties and behaviour of complex biological systems in terms of their components and their interactions.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in