Pan-cancer analysis of genomic aberrations in relation to cell cycle activity levels

Published in Cancer

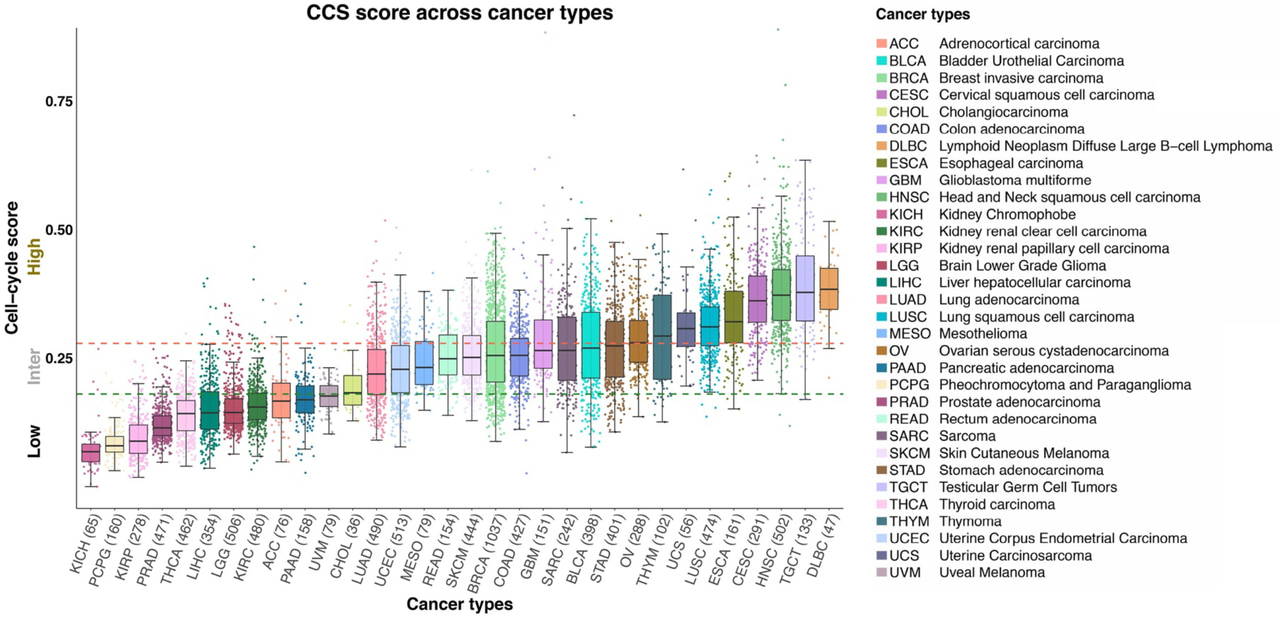

Genomic alterations resulting in loss of control over the cell cycle is a fundamental hallmark of human malignancies. Whilst pan-cancer studies have broadly assessed genomic aberrations within oncogenic signalling pathways, analyses based on the magnitude of pathway activity are lacking. To this end, we aimed to explore the DNA mutations and chromosome arm-level aneuploidy within tumours with Low, Intermediate and High cell cycle activity subgroups using pan-cancer data with matching clinico-pathological information from 9,515 patients.

As noted above, the idea for this study came while teaching undergraduate students. When preparing lecture material and considering cancer and the cell cycle at its most basic level, we wondered: Which cancer types generally display the highest levels of cell cycle activity? Are the same mutations found in tumours with high cell cycle activity as those with low? Can simply measuring cell cycle activity predict how long cancer patients live with their disease? Luckily, through the expansive and dedicated work of the pan-cancer research consortium, we could answer these questions using well-annotated and meticulously curated data resources from the pan-cancer atlas project, for this we own the pan-can researchers a huge debt of gratitude.

Using their data, we found that cell cycle activity varies broadly across and within cancers and that whilst TP53 and PIK3CA mutations dominated all cell cycle subgroups, their frequency increased with increasing cell cycle activity levels. Notably the number of BRAF mutations was significantly less in tumours with High cell cycle activity relative to Intermediate/Low. More broadly, we also showed that independent prognostic information can indeed be derived on a pan-cancer level from a simple measure of cell cycle activity.

Another major finding with the potential to change how we think about biomarkers was our result showing that deriving cycle cycle activity tertiles on a pan-cancer level provided more prognostic information for four cancer types then deriving tertiles within each cancer type individually. Considering this more generally, when we take one cancer type and say that a gene is "low" or "highly" expressed we make this assertion considering only the variance in a limited number of tumour samples. However, if we look across 11,000 tumour samples covering 32 different cancer types and see that a gene is "highly" expressed, we can be far more confident in relative terms that a gene of interest does show high expression. Boiling this down further for the sake of simplicity: When we say "high" expression, how high do we mean? Pan-cancer analyses help us to state this with a much greater degree of certainty.

We are extremely proud of this work, in particular as it is both novel and exciting from a research perspective whilst also providing us with definitive answers (and figures) that we can give/ show to students in an educational setting. We hope you find it as useful and informative as we do. Full article can be found here: https://rdcu.be/b49yD

Follow the Topic

-

Oncogene

This journal aims to make substantial advances in our knowledge of processes that contribute to cancer by publishing outstanding research.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in