Personality intervention affects emotional stability and extraversion similarly in younger and older adults

Published in Social Sciences and Behavioural Sciences & Psychology

In this study, recently published in Communications Psychology, we examined processes and age differences in personality interventions. Participants were younger adults, largely in their twenties, and older adults in their sixties and seventies who wanted to become more emotionally stable, better able to handle stress and difficult interpersonal situations. To achieve this, they participated in an eight-week in-person training and received tasks to practice during each week. Before, during, after the training, and up to one year later, we measured their personality characteristics Emotional stability and Extraversion with self-report questionnaires and an indirect test (IAT). During the training, we also asked in weekly reports how they were doing with respect to handling stress and social interactions and how intensely they had practiced their tasks. We would have loved to obtain more daily or indirect measures, such as with smartphone sensing, yet focused on the current study design to keep the demands for the participants reasonable. To examine potential causal effects of the training, we implemented a random control group, which was a passive waitlist group in our study. This allowed us to compare the results of the training group to a group of participants who had signed up for the study but had not received any training yet.

Key findings

Two findings stand out:

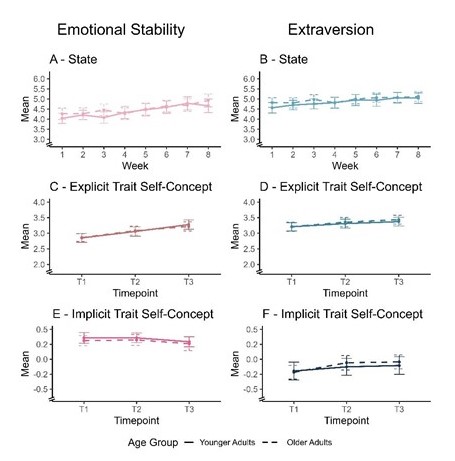

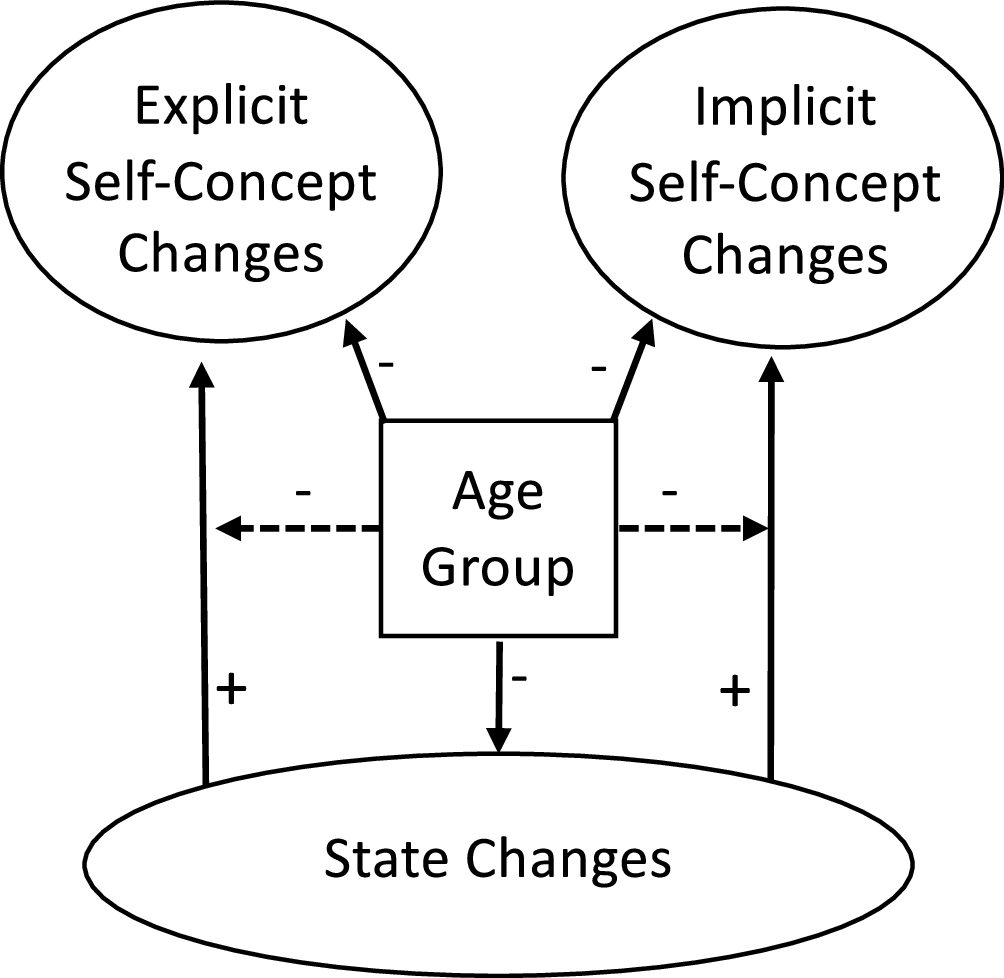

First, during our intervention, both weekly reported behaviors and traits of Emotional stability and Extraversion changed on average in the direction, which the participants desired, and to a similar extent for BOTH younger and older adults (see Figure 1). The average change in both age groups was so similar that you can hardly distinguish the two lines in the figure. This was not expected and is quite striking because many other things become more difficult to learn for older people, such as a new language or a musical instrument. We safeguarded the findings based on a relatively small sample of 165 participants with estimations of Bayes factors.

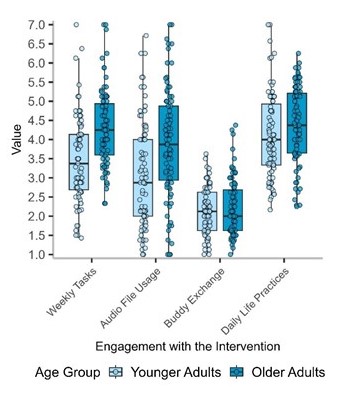

The second important finding shows that older adults reported more engagement with the training materials and the weekly tasks, whereas younger and older participants reported similar amounts of daily practice as well as contact with their training buddy (Figure 2). Thus, participant motivation and time spent practicing seem to explain the absent age differences. It is important to keep in mind that younger and older participants did not differ initially in their motivation to change Emotional stability, and younger adults had even stronger motivation to become more socially capable.

We do not want to hide an unexpected finding: Indirectly measured Emotional stability did not increase during the intervention (Figure 1). One interpretation, in line with current conceptions of personality traits, is that people’s implicit concepts of their personality are more difficult to change – yet this interpretation is challenged by the significant changes in the implicit concept of Extraversion. Further contradicting this interpretation, a recent study by one of the co-authors, Wiebke Bleidorn, observed changes in implicit measures of Emotional stability, suggesting that the lack of effects may be specific to the present sample or intervention.

A story behind our study

The study did not only change our participants, it also changed me (Disclaimer: this is a subjectively perceived change, which is a problematic measurement approach that would have to be complemented by other measures such as observer reports from my colleagues in the project.). It has been seven years now since the planning of the project and four years since its start as a collaboration of a developmental personality psychologist, a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist, and two PhD students. Throughout these years, I have (a) gained a much deeper understanding of the (therapeutic) change processes, (b) reflected and perhaps shaped my own development much more, and (c) become awed and humbled about human motivation and capabilities of change. The latter occurred because more than a thousand adults were interested in our intervention, yet some were too burdened for what we could offer and some found the study accompanying the intervention too demanding. Regarding these three (perceived) personal changes, my researcher perspective has to acknowledge that I do not have a control group for myself and the change might have occurred anyway because of my interest in humanistic growth. Still, the joy and knowledge gained during the project is very tangible and led to planning the next projects.

What is next?

As is quite common in research projects, not all hypotheses were confirmed and some questions remain open. For example, how changes in thoughts and behaviors contribute to changes in more lasting explicit and implicit self-concepts of personality traits, and why differences occur between individuals. The two PhD students, Gabriela and Kira, are off to new endeavors, yet we hope to continue this work with new projects. In Heidelberg, we plan to use Virtual Realities (VR) to combine the effectiveness of in-person interventions with the scalability of smartphone interventions (e.g., PEACH Stieger et al., 2021, CHILL, Wright et al., 2025). Such digital interventions could address human desires for personal development and offer further scientifically grounded support for personality interventions. Across the lifespan, people actively want to shape their relationships and ways of handling emotional challenges. Access to basic knowledge about these processes, without pathologizing societies, can serve as a practical resource in supporting individuals who wish to develop or adjust aspects of their lives. And our study and others (Roberts et al., 2017) show that changes in these domains are possible—no matter whether people are 28 or 72 years old.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Psychology

An open-access journal from Nature Portfolio publishing high-quality research, reviews and commentary. The scope of the journal includes all of the psychological sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Intensive Longitudinal Designs in Psychology

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Replication and generalization

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Dec 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in