Quantifying the global eco-footprint of wearable healthcare electronics

Published in Bioengineering & Biotechnology, Electrical & Electronic Engineering, and Economics

When I first tried to quantify the environmental footprint of a wearable device, I realized that we might have been asking the wrong questions.

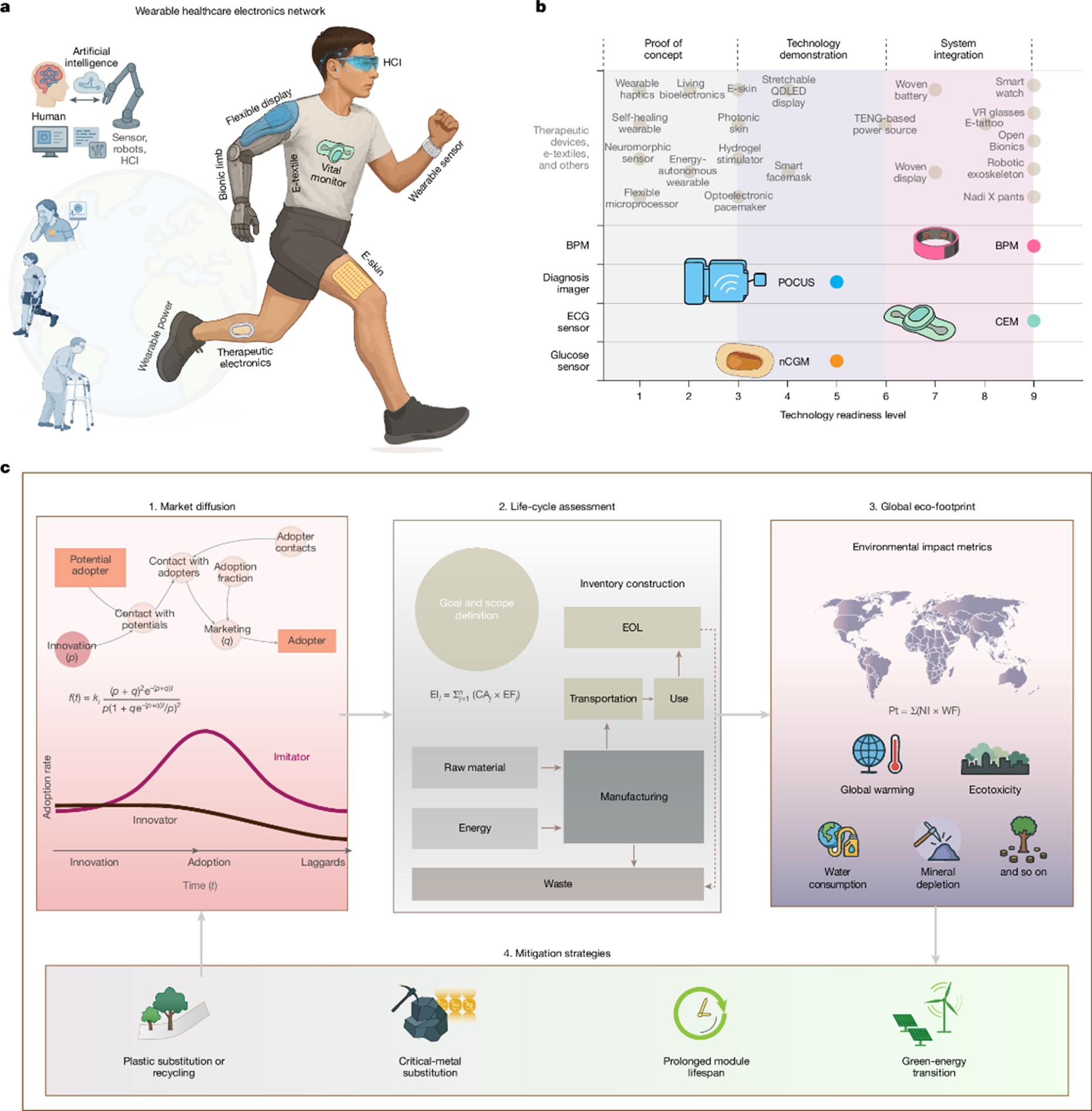

Wearable electronics are often portrayed as the future of healthcare. They are lightweight, flexible, and intelligent, and they frequently appear on the covers of leading journals as symbols of technological progress. Like many researchers in the field, my early focus was on how to make these devices more sensitive, more stable, and more compatible with the human body.

Yet as the research evolved, a different question began to surface:

What happens when these devices move beyond the lab and scale to billions of units in the real world?

This question did not arise from a grand theoretical argument, but from a surprisingly concrete calculation. When I approached wearable medical devices from an environmental engineering perspective and attempted to build a full life-cycle inventory, I found that the dominant environmental impacts were not driven by the plastic packaging that we often debate, nor by how “soft” or “biocompatible” a device appears. Instead, they were rooted in the integrated circuits, the use of critical metals, and the energy-intensive manufacturing processes behind them.

This realization challenged a prevailing intuition in sustainable electronics research: that material substitution alone—especially in polymers—would be sufficient to meaningfully reduce environmental impacts.

My training is in environmental engineering, while my advisor, Professor Bozhi Tian, leads a laboratory specializing in bioelectronic fabrication and flexible devices. Bridging these two perspectives was far from straightforward. Environmental engineering emphasizes systems, cumulative impacts, and long-term consequences, whereas cutting-edge electronics research is often driven by performance, micro-scale design, and functional breakthroughs. There was no established roadmap for integrating these viewpoints.

Out of this tension, our study gradually took shape. Together with Professor Fengqi You and Bingzheng Wang from Cornell, we moved beyond individual devices and developed an integrated framework that connects technology maturity, market diffusion, and full life-cycle environmental impacts. This approach allowed us to reassess wearable medical electronics not as isolated innovations, but as technologies embedded within global production and consumption systems.

The results were not always comfortable, but they were revealing. Even when the footprint of a single device appears modest, large-scale deployment can translate into substantial carbon emissions, ecological toxicity, and electronic waste. Perhaps more unexpectedly, many widely discussed “green” strategies—such as recyclable or biodegradable plastics—offer limited benefits compared with system-level interventions, including alternative conductor materials and circuit architecture redesign.

This work is not intended to question the promise of wearable electronics. On the contrary, it is precisely because these technologies are likely to scale rapidly that their environmental consequences must be understood early, not after widespread adoption.

For us, this paper also represents a shift in how we think about innovation. It moves from asking how to make electronic devices better, to asking how successful technologies reshape the environmental systems they depend on. We hope that this system-level perspective can help guide the next generation of wearable electronics—toward designs where performance, scalability, and environmental responsibility are optimized together, rather than traded off against one another.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature

A weekly international journal publishing the finest peer-reviewed research in all fields of science and technology on the basis of its originality, importance, interdisciplinary interest, timeliness, accessibility, elegance and surprising conclusions.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in