Real-world outcomes following biochemical recurrence after definitive therapy with a short prostate-specific antigen doubling time: potential role of early secondary treatment

Published in General & Internal Medicine and Pharmacy & Pharmacology

Key findings

- Results for time to metastasis and overall survival (OS) were similar for our high-risk patients who received early androgen deprivation therapy (ADT) to historical data from all patients (both low- and high-risk) with biochemical relapse who received delayed ADT, despite our patients being further along in their recurrence journey (higher prostate-specific antigen [PSA] levels).

- Further research will confirm whether this is due to a benefit of early ADT or improved prostate cancer outcomes over time.

Why did we do this research?

Real-world data are limited for patients with nonmetastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (nmCSPC) and biochemical recurrence (BCR) after primary therapy. Our current understanding of the natural history of this type of recurrence is largely based on data from the Johns Hopkins Hospital. In these historical studies, most patients received delayed ADT at metastasis rather than early ADT before metastasis1,2.

However, although real-world data show that most patients who receive ADT after recurrence do so before metastasis3, the benefits of early ADT remain unclear. In TOAD, a clinical trial, early ADT improved OS in patients with BCR or non-curable prostate cancer compared with delayed ADT4; but no OS differences were observed when results were combined with the ELAAT clinical trial5. Moreover, the natural history of early ADT and whether PSA doubling time (PSADT) remains as equally prognostic in patients receiving early versus delayed ADT also remains unclear. This is particularly relevant for patients with a PSADT of <15 months, who had worse outcomes when receiving delayed ADT compared with those who had a PSADT of >15 months6.

Our study aimed to assess real-world outcomes in patients with this type of prostate cancer as a function of PSADT following recurrence after definitive treatment. We also compared our results with historical controls of patients who were largely treated with delayed ADT to put our findings within the context of prior studies.

How did we conduct this research?

In our retrospective real-world study7, we extracted data for patients with this type of prostate cancer and recurrence after definitive therapy from the Veterans Health Administration database (VHA; January 1, 2006 to June 22, 2020; Figure 1). Patients were required to have previously received definitive treatment with radical prostatectomy or external radiotherapy and to have BCR with a PSADT of ≤15 months. We assessed outcomes in patients by PSADT cohort (rapid vs less rapid; Figure 1).

Figure 1. Study methods and assessed outcomes.

BCR, biochemical recurrence; MFS, metastasis-free survival; nmCSPC, nonmetastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer; OS, overall survival; PSADT, prostate-specific antigen doubling time; VHA, Veterans Health Administration.

What did we find?

The results of our analysis showed that when compared with patients who had less rapid PSADT (>9 to ≤15 months), patients with rapid PSADT (≤9 months) experienced worse outcomes for time to antineoplastic therapy, metastasis, metastasis-free survival (MFS), and OS (Table 1). The median time to first systemic antineoplastic therapy was <1 year for patients with rapid PSADT and >2 years for patients with less rapid PSADT.

Table 1. Outcomes after BCR among patients with nmCSPC by PSADT cohort7.

|

Median, months |

Rapid PSADT |

Less rapid PSADT |

|

Time to antineoplastic therapy |

11.4 |

28.3 |

|

Time to metastasis |

102.4 |

Not reached |

|

MFS |

76.1 |

106.3 |

|

OS |

120.5 |

140.5 |

BCR, biochemical recurrence; MFS, metastasis-free survival; OS, overall survival; PSADT, prostate-specific antigen doubling time.

Exploratory analyses

When compared with PSADT of >12 to ≤15 months, a shorter PSADT of ≤3 or >3 to ≤9 months was associated with a higher risk of metastasis or death (MFS). A PSADT of ≤3 months was associated with a higher risk of death (OS) compared with a PSADT of >12 to ≤15 months.

These results further support the prognostic role of PSADT demonstrated in previous studies of patients who received delayed ADT1,2. These results also extend the prognostic role of PSADT to patients who, in most cases, received early aggressive secondary treatment for recurrence.

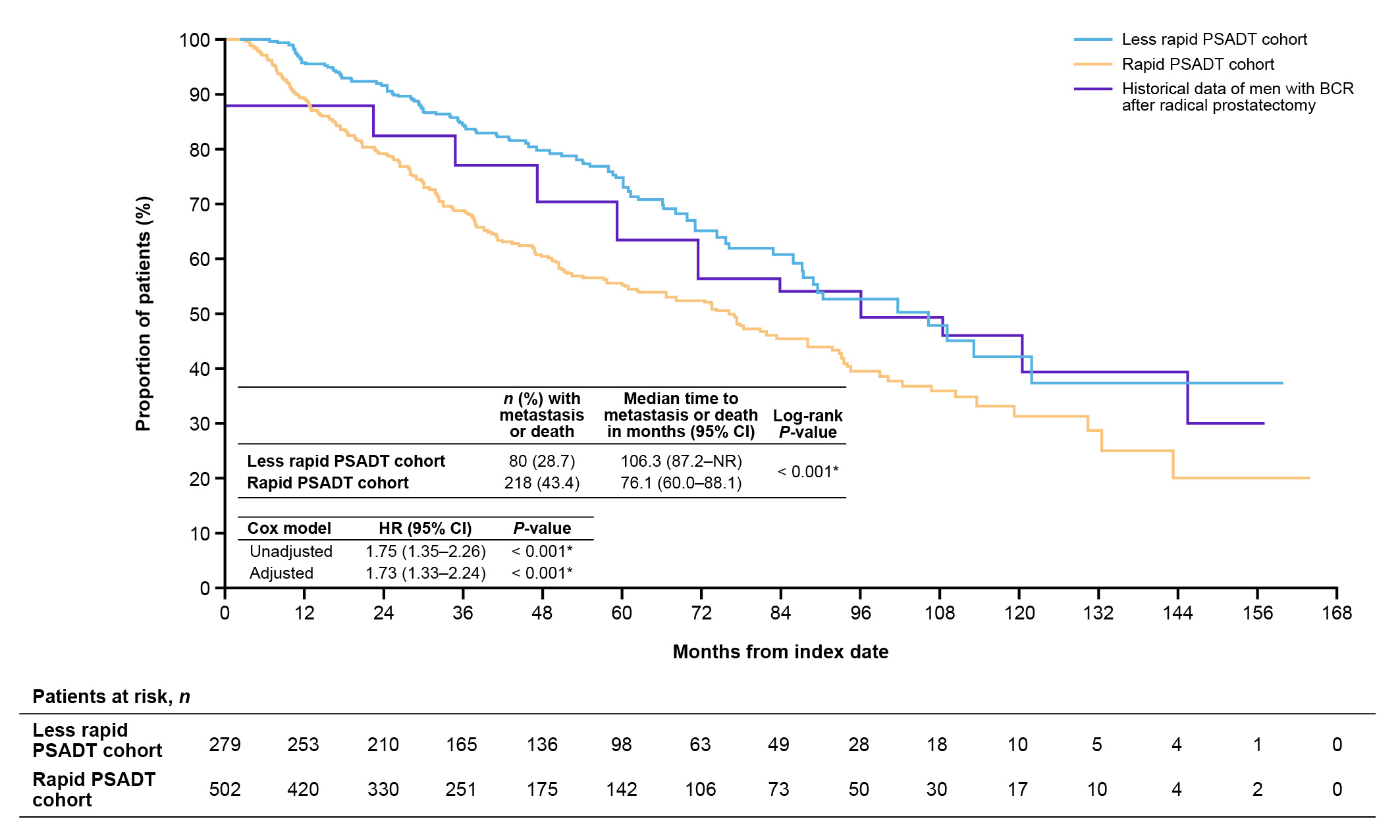

Comparing our time to metastasis results with historical data

We compared our results in patients with early ADT with the Johns Hopkins data of patients who received delayed ADT. We observed that the median time to metastasis for patients with rapid PSADT in our study (102 months; 8.5 years) was similar to historical data among all patients (8 years; Figure 2)1. Importantly, the historical analysis included all patients who had a biochemical relapse, not just those classified as high-risk. Our study also used a higher cut-off for PSA to define recurrence (≥1 ng/mL vs ≥0.2 ng/mL)1,7. We selected a PSA cut-off of ≥1 ng/mL for recurrence to align with the cut-off used in the EMBARK study8. The results of EMBARK led to the approval of enzalutamide to treat patients with nmCSPC and high-risk BCR.

Figure 2. MFS after BCR among patients with nmCSPC by PSADT cohort, including historical Johns Hopkins data1,7.

BCR, biochemical recurrence; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MFS, metastasis-free survival; nmCSPC, nonmetastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer; PSADT, prostate-specific antigen doubling time.

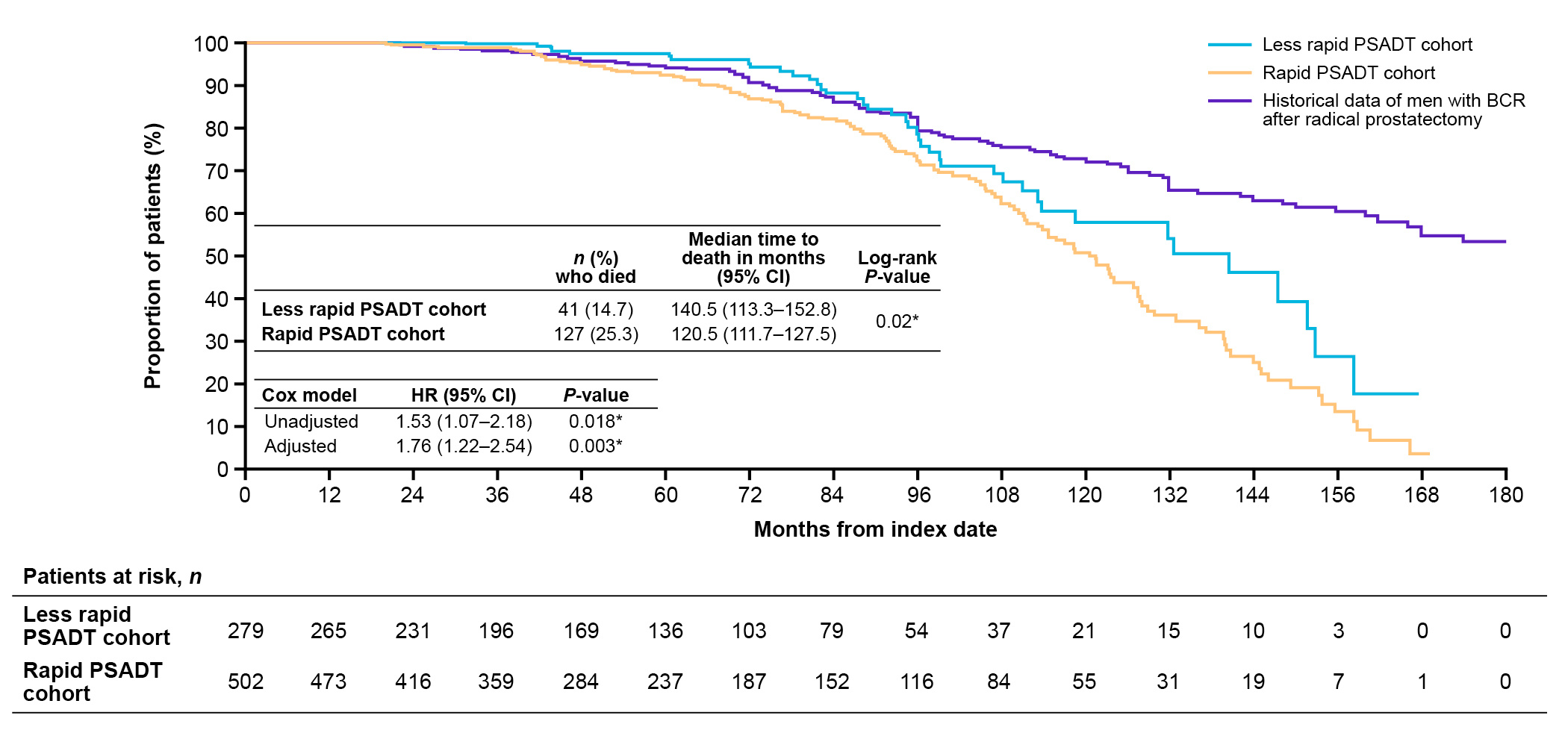

Comparing our OS results with historical data

For median OS (120.5 months; 10 years; Figure 3), the results for patients with rapid PSADT in our study aligned with previous results in patients with a PSADT of 3 to 8.9 months from longer term follow-up from Johns Hopkins (data for historical 3 to 8.9 month PSADT group not shown)2. However, our cohort appeared slightly older than the historical cohort2. The Johns Hopkins PSADT 3 to 8.9 month group also did not include patients with PSADT <3 months, unlike our PSADT ≤9 month group, which included these very high-risk patients2. Also, as noted above, our PSA cut-off was higher than the cut-off used for the historical study. This shows that despite our patients being further along in their recurrence journey, outcomes were similar.

Figure 3. OS after BCR among patients with nmCSPC by PSADT cohort, including historical Johns Hopkins data2,7.

BCR, biochemical recurrence; CI, confidence interval; HR, hazard ratio; MFS, metastasis-free survival; nmCSPC, nonmetastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer; PSADT, prostate-specific antigen doubling time.

What do our findings mean?

Taken together, the similar results for time to metastasis and OS observed between our high-risk patients and historical data of all patients suggests the possibility that early secondary treatment of high-risk recurrence improves outcomes. This is because our patients appeared slightly older, were further along in their recurrence journey, and would, therefore, be expected to have worse outcomes than all patients with this type of recurrence from historical data.

Alternatively, as new therapies are introduced and stage migration continues, these observations could be explained by the improving outcomes in prostate cancer over time9. Given the retrospective nature of our study, we cannot infer cause and effect. Furthermore, caution should be taken when comparing study results as variables can differ between studies and affect both the results and conclusions. More studies are needed to further understand the reasons for the improved outcomes in this contemporary cohort of patients treated with aggressive, early, secondary therapy in relation to the historical Johns Hopkins data.

In summary, this study of VHA data over a 15-year period demonstrates that patients with nmCSPC, high-risk BCR, and a rapid PSADT following definitive therapy had worse outcomes than patients with a less rapid PSADT. Intriguingly, patients with a rapid PSADT from the VHA, who were heavily treated with secondary treatment, appeared slightly older, had potentially poorer health, and had higher PSA levels at recurrence than patients from the historical Johns Hopkins data, had similar outcomes to patients who did not receive aggressive secondary treatment. Further study will determine whether this reflects the benefits of early aggressive treatment of high-risk BCR or improved outcomes over time.

References

1 Pound, C. R., Partin, A. W., Eisenberger, M. A., Chan, D. W., Pearson, J. D. & Walsh, P. C. Natural history of progression after PSA elevation following radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 281, 1591–1597 (1999).

2 Freedland, S. J. et al. Death in patients with recurrent prostate cancer after radical prostatectomy: prostate-specific antigen doubling time subgroups and their associated contributions to all-cause mortality. J Clin Oncol. 25, 1765–1771 (2007).

3 Moradzadeh, A. et al. The Impact of Comorbidity and Age on Timing of Androgen Deprivation Therapy in Men with Biochemical Recurrence after Radical Prostatectomy. Urol Pract. 8, 238–245 (2021).

4 Duchesne, G. M. et al. Timing of androgen-deprivation therapy in patients with prostate cancer with a rising PSA (TROG 03.06 and VCOG PR 01-03 [TOAD]): a randomised, multicentre, non-blinded, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol. 17, 727–737 (2016).

5 Loblaw, A. et al. Timing of androgen deprivation therapy for prostate cancer patients after radiation: Planned combined analysis of two randomized phase 3 trials. J Clin Oncol. 36, 5018–5018 (2018).

6 Freedland, S. J. et al. Risk of prostate cancer-specific mortality following biochemical recurrence after radical prostatectomy. JAMA. 294, 433–439 (2005).

7 Freedland, S. J. et al. Real-world outcomes following biochemical recurrence after definitive therapy with a short prostate-specific antigen doubling time: potential role of early secondary treatment. Prostate Cancer Prostatic Dis. 10.1038/s41391-024-00894-0 (2024).

8 Freedland, S. J. et al. Improved Outcomes with Enzalutamide in Biochemically Recurrent Prostate Cancer. N Engl J Med. 389, 1453–1465 (2023).

9 George, D. J. et al. 1384P Treatment patterns and overall survival (OS) in metastatic castration-sensitive prostate cancer (mCSPC) from 2010 to 2019. Ann Oncol. 33, S1175–S1176 (2022).

Acknowledgments

Medical writing and editorial support were provided by Adam Anazim, BSc, and Rosie Henderson, MSc, of Onyx (a division of Prime, London, UK) and funded by the sponsors. Pfizer’s generative artificial intelligence (AI) assisted technology, MAIA (Medical Artificial Intelligence Assistant) was used in the production of this blog post to produce the initial draft. After using this tool, the author reviewed and edited the content as needed and takes full responsibility for the content of the blog post.

Funding

This study was sponsored by Pfizer Inc. and Astellas Pharma Inc., the co-developers of enzalutamide.

Stephen J Freedland reports consulting for Astellas Pharma Inc., AstraZeneca, Bayer, Eli Lilly, Exact Sciences, Janssen, Merck, Pfizer Inc., Sanofi, and Sumitomo Pharma America Inc. (formerly Myovant Sciences Inc).

Follow the Topic

-

Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases

This journal covers all aspects of prostatic diseases, in particular prostate cancer, the subject of intensive basic and clinical research world-wide.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in