Reliance on fossil fuels increases during extreme temperature events in the continental United States

Published in Earth & Environment and Materials

The intensity and frequency of winter storms, droughts, heatwaves, and other extreme events have increased worldwide in recent decades as a result of climate change, and numerous studies expect the trend to further intensify and occur more frequently. In turn, extreme events have been shown to impact electricity systems, causing disruptive and sometimes deadly outages. Large-scale outages are due to a regional imbalance between electricity generation and demand, which can occur because of failures in electricity generation or transmission infrastructure, because surging demand outstrips available generation, or both. For example, very high temperatures decrease the operating efficiency of thermal power plants and solar photovoltaics, droughts limit hydroelectric generation, and winter storms freeze cooling and fuel pipes or wind turbines. Meanwhile, extreme heat greatly increases electricity demand for air conditioning, and extreme cold increases electricity demand in regions where some heating systems are electric.

Although the relative impacts of extreme climate events on the reliability of fossil and renewable electricity generators are not clear, there are widespread concerns that renewable energy systems will be more vulnerable to failure during extreme conditions. If fossil energy sources prove more reliable, increasing frequency and intensity of extreme events would work against mitigation efforts. Yet many states, countries, and companies have announced plans to drastically reduce fossil energy as they target net-zero emissions. Among all scenarios assessed by the most recent IPCC report (AR6), renewable energy sources supply an average of 63% of the world’s primary energy in the year of 2070 when global CO2 emissions reach net-zero (n=476, which indicates number of the scenarios). For 1.5 and 2C net-zero scenarios, renewable sources represent an average of 64% of primary energy when they reach net-zero CO2 emissions in the year of 2068.

Here, therefore, we systematically evaluate energy sources, the carbon intensity (emission per unit of electricity generated) of electricity, and daily temperatures across the U.S. over the period of 2019-2023 to quantitatively characterize how the electricity production systems responded to extremes in recent years. Details of our analytical approach are available in the Supplementary Materials. In summary, we use electricity generation data from the U.S. Energy Information Administration (EIA) and air temperature data from the ERA5-Land reanalysis to assess the sensitivity of daily, state-level electricity generation, carbon emissions and carbon intensity to population-weighted surface air temperatures (calculated from pixel-level), and especially temperature extremes. Note that extreme events here, are based on long-term historical air temperature data extreme detection, which will only see the change in unbiased variance.

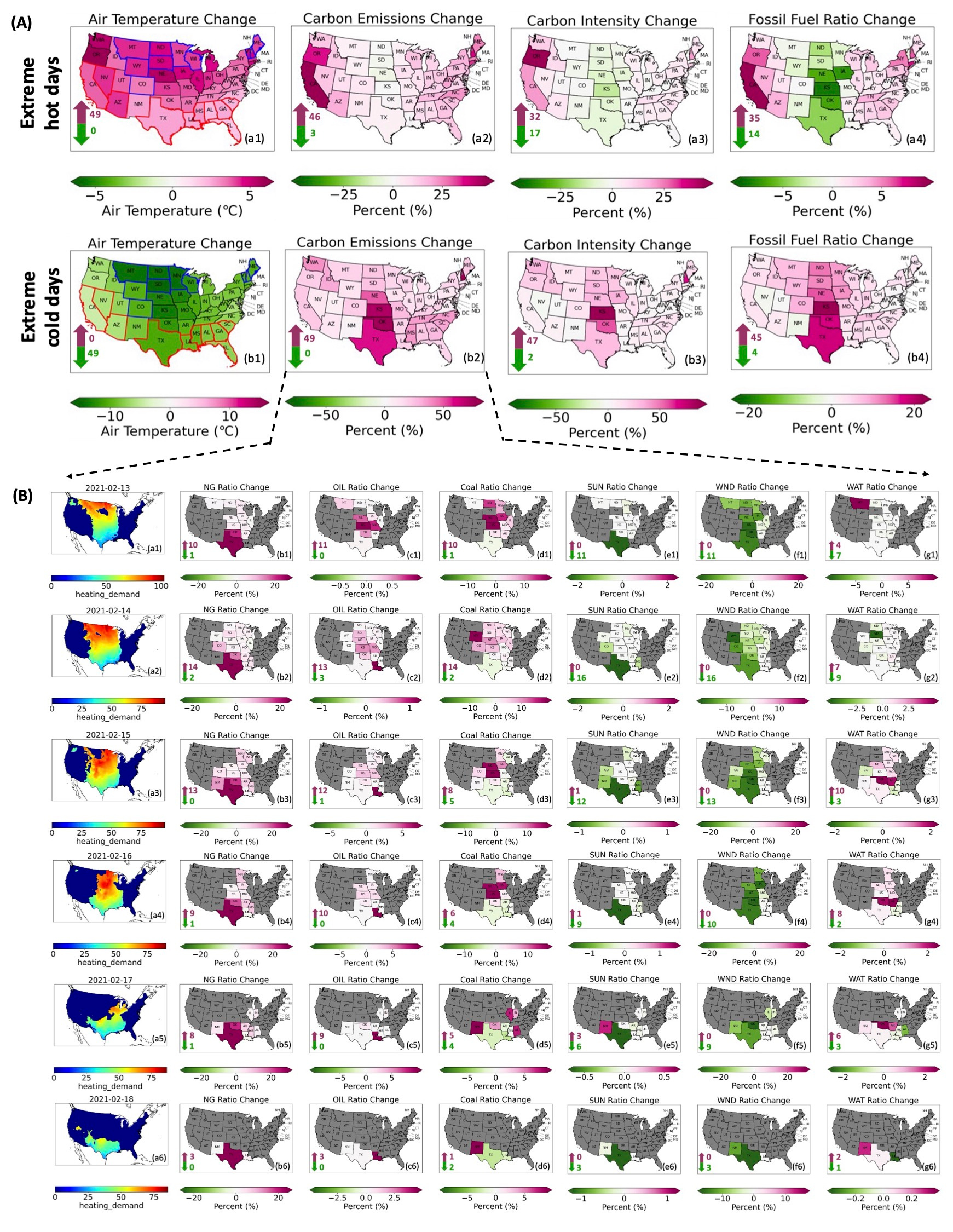

Figure 1. Maps of changes of air temperature, carbon emission, carbon intensity and fossil fuel ratio of power production for all hot and cold extreme temperature events.

Our analysis mainly demonstrated that,

1) During the extreme events, the electricity production becomes dirtier with increasing carbon intensity and carbon emissions.

2) In general, extreme events increase carbon emissions and reliance on fossil fuel across the U.S. states. Specifically, extreme cold events will increase 23.4% carbon emissions on the basis of the normal Ta periods and reliance on the share of fossil fuels by increasing 14.7% in 48 U.S. states on average. Similarly, the extreme hot events will increase 14.1% carbon emissions in 46 states and 6.7% fossil fuels usage in 37 states on average, on the basis of normal Ta periods. In addition, the wind power reductions during extreme cold days and increase during extreme hot days over the central U.S. are also clearly seen. Although the issue of frozen wind turbines has been studies many years, the wind power seems still affected more during extreme cold days than extreme hot days.

3) Cold states are more adapted to extreme cold days and increase their emissions less than warm states. During the extreme cold days, carbon emissions increase 4.4% as Ta declines by 1℃ (compared to the normal air temperature periods) in the warm states. However, for cold states in extreme cold days, carbon emissions only tend to increase 1.4% as Ta declines by 1℃. Our further analysis for warm states shows that emissions increase by 4.4% per 1℃ decreases during the extreme cold days and increase 3.8% per 1℃ increases during the extreme hot events, respectively. Therefore, our results suggest that the extreme cold events have a more serious impact than extreme hot events for warm states.

Overall, our study demonstrates for the first time, that extreme climate events can increase the carbon emissions and the carbon intensity of the energy production, increasing the reliance on carbonated sources of energy and reducing the capacity of renewables. To therefore achieve the goals of net zero emissions, the sizing and development of renewables should be made while accounting not only for changes in demand and mean climate but also targeting reliance on extreme events, which are increasing in frequency and intensity with climate change. This will pose a further challenge for the transition to a fully renewable-based electricity production system.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in