Resilient algae may speed up Greenland ice melt

Published in Earth & Environment and Ecology & Evolution

How it all started

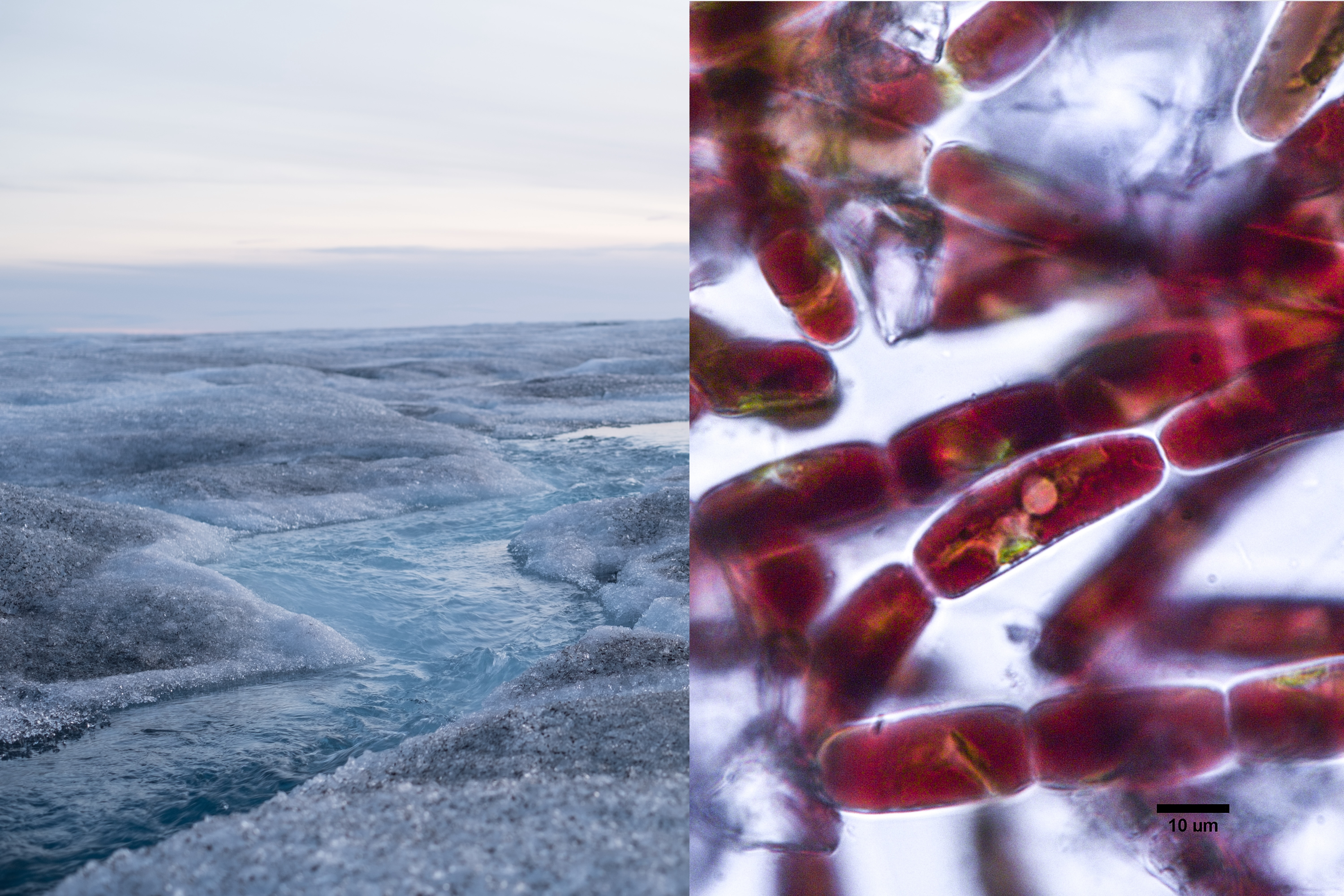

I was already fascinated by life in cold and icy habitats when I decided to study glacier ice algae as part of my PhD project at Aarhus University. I had seen and walked on glaciers before, but I never imagined that glacial ice could harbour such a great abundance of microbes. That changed when my PhD research brought me to the glaciers and ice sheet of Greenland together with a team of dedicated scientists of the Deep Purple research project. For the first time, I stood on the vast, thick ice mass of Greenland. Astonishingly, the ice surface is teeming with microbial life, and one particular algae stands out: blooms of so-called glacier ice algae cover large areas of the ice surface, darkening it due to their dark pigmentation. What I had previously thought was just "dirt"—minerals, soil, or debris on the ice—turned out to be glacier ice algae. Their blooms are known to accelerate ice melt by lowering the ice’s reflectivity (albedo), meaning that more sunlight is absorbed instead of being reflected. However, it remains unclear how their extent will change with rising temperatures and rapid ice loss.

I started asking myself: What do these algae need to grow? What determines where they live? How fast do they grow? And what limits their distribution? I found out that we were still in the dark about what these algae truly need and at which rate they grow and colonize ice surfaces.

I was intrigued - and so began my four-year journey involving extensive experimental planning, international collaborations, more fieldwork on the ice sheet, a polar bear fence, expedition cooking classes, moments of failure and frustration, deep learning about glacier ice algae, and, finally, a publication.

Embarking on a Helicopter to the Greenland Ice Sheet

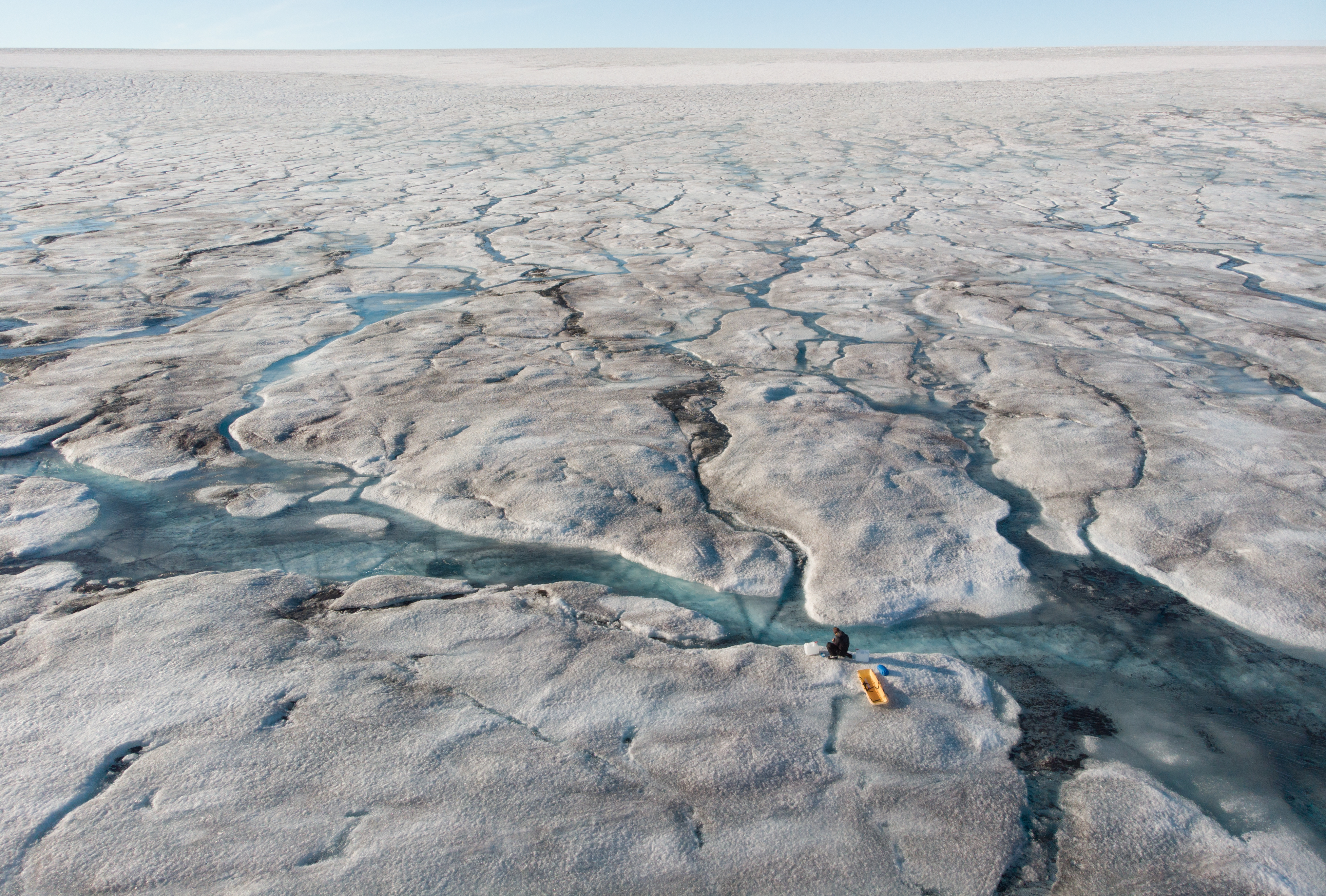

After weeks of planning and rigorous protocol development we headed to the Greenland Ice Sheet in the summer of 2020—right in the middle of the global COVID-19 pandemic. Nine scientists and about two tons of equipment, were dropped off by a helicopter on the ice in the middle of nowhere. First priority: safety (e.g. spotting moulins, which are deep holes in the ice), setting up a camp, sorting and ensuring food supply and a lab tent to work in. We collected surface ice samples, melted them slowly, and incubated them in bottles with stable isotopes and nutrients to track their carbon and nitrogen uptake. After ~30 hours, we processed all our samples. Fieldwork on an ice sheet can be intense. The conditions are tough, unpredictable, and sometimes storms force you to abandon experiments to secure your camp. But we successfully collected our samples, transported them back to Denmark, then to Germany, and finally to Stockholm for the first single-cell measurements of these algae.

Measuring What Our Tiny Friends Are Doing Using Single-Cell Imaging

Before our field expedition, I happened to meet Dr. Katharina Kitzinger from the Max-Planck-Institute for Marine Microbiology (MPI) at a friend’s birthday party. As we got talking about science, I mentioned my research on glacier ice algae and my curiosity about a high-resolution technique for measuring species activity. She smiled and said, ‘Oh, I work with SIMS!’—she did not mean the computer game that consumed too many hours of my life, but Secondary Ion Mass Spectrometry, a powerful method for tracing nutrient uptake at the single-cell level. At the Natural History Museum in Stockholm, I was granted 48 hours of measurement time—an extremely valuable opportunity, since these measurements are time-consuming and expensive. I also learned about another powerful tool: SEM-EDX (Scanning Electron Microscopy with Energy Dispersive X-ray Spectroscopy). This technique not only captures high-resolution images of cells but also reveals their elemental composition—like a chemical fingerprint. I later used this method back at the MPI in Germany.

What did we Discover?

Our study provides the first single-cell data on the elemental composition of glacier ice algae, as well as their nutrient and carbon uptake. We found that these algae are highly efficient in utilizing the limited nutrient resources available on the ice, allowing them to thrive even in nutrient-poor conditions. They store phosphorus internally—a key adaptation for surviving in nutrient-poor ice environments- and take up nitrate and ammonium efficiently. Furthermore, their carbon fixation did not increase after nutrient additions, suggesting they were not nutrient-limited.

Tiny Algae, Big Impact: the future fate of ice algal blooms under a warming climate

With increasing temperatures and rainfall on the Greenland Ice Sheet, new bare ice areas are exposed which were previously covered by snow year around. The remarkable adaptability of glacier ice algae to the nutrient poor habitat, combined with their plasticity in nutritional composition and clear mechanisms for nutrient storage, suggests that glacier ice algae could expand their colonization further inland on the Greenland Ice Sheet, enhancing ice darkening and further accelerating melt. Our findings on glacier ice algae’s growth and nutrient uptake provide insights into their future expansion—and their role in accelerating ice melt under climate change.

Our study adds to the growing body of research emphasizing the importance of microbiology in large-scale physical processes and the need to incorporate biological factors into climate models. Nature is complex, and we are only beginning to grasp the ways in which these tiny microbes shape our planet’s changing landscapes.

Further reading (in addition to the paper):

https://tech.au.dk/en/about-the-faculty/news/show/artikel/resilient-algae-may-speed-up-greenland-ice-melt

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Communications

An open access, multidisciplinary journal dedicated to publishing high-quality research in all areas of the biological, health, physical, chemical and Earth sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Women's Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Advances in neurodegenerative diseases

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 24, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in