Scaffolding the Scaffolder: How Artificial inteligence Can Support Parents Without Replacing Them

Published in Social Sciences, Electrical & Electronic Engineering, and Education

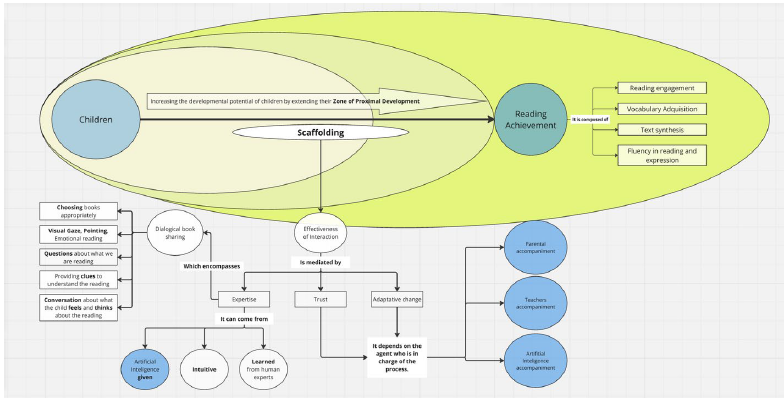

In those quiet, familiar moments, something developmentally profound is taking place. Shared reading is not just about learning words or following a story. It is a rich social interaction in which adults guide attention, interpret emotions, ask questions, and connect the story to the child’s own experiences. Developmental psychology describes this kind of adaptive, responsive support as scaffolding: the process by which an adult or an expert pair helps a child achieve beyond what they could do alone. Those everyday moments of shared reading and domestic interactions are among the most powerful developmental experiences in early childhood. They are where language expands, attention strengthens, emotions are interpreted, and thinking skills grow. The complexity and enhancement potential of those moments and experiences are guiding our work, illustrated in Fig. 1, and integrating these concepts into a model for how scaffolding, enacted through practices like Dialogical Book Sharing (DBS), facilitates desired learning outcomes.

Fig. 1 Theoretical Framework for AI-Assisted Reading.

Developmental science refers to the support adults provide in these moments as “scaffolding.” Good scaffolding means adjusting the complexity in Fig. 1 to help at the child’s level, not too much, not too little, so the child can do just beyond what they could manage alone.

Yet scaffolding presents a paradox. It is central to development, but it is also extremely difficult for parents to observe themselves while it is happening. These interactions unfold in seconds, are emotionally charged, and involve voice tone, gestures, timing, and responsiveness. Even trained researchers need video replay to analyze them carefully. Parents, immersed in interaction, simply cannot self-monitor in real time. As a result, common advice such as “ask more questions” or “be responsive” often feels abstract and hard to translate into concrete behavior.

Our study asked a simple but far-reaching question: can artificial intelligence help parents reflect on how they support their children, without replacing the human relationship at the heart of development? This question led us to develop GABRIEL, an AI system designed not to teach the child directly, but to support the caregiver.

Instead of positioning AI as a judge or instructor, we designed GABRIEL as a reflective mirror. Parents record a short reading interaction using a smartphone. The system analyzes the video and produces structured descriptions of key interaction moments, scores based on established developmental scales, and a brief, non-judgmental reflection highlighting strengths and one area to consider. The AI does not intervene during interactions. It works after the moment has passed, supporting adult reflection rather than directing behavior in real time.

In practical terms, this system functions somewhere between a developmental psychologist, a video rater, and a structured reflection tool, but in a form that could be scalable and accessible. That scalability is important. The study was conducted with families in Colombia, using typical smartphones and real-world recording conditions, not laboratory equipment. In many contexts around the world, families do not have access to ongoing developmental guidance or specialized assistance. Yet mobile technology is widespread even in LMIC. If AI can responsibly support parental reflection, it may contribute to reducing developmental inequities, not by replacing care, but by strengthening it.

A central part of the research was testing whether the system’s evaluations aligned with human observers trained in developmental psychology. As GABRIEL incorporated more psychological theory and more sophisticated video processing, its assessments became significantly closer to human ratings. Interestingly, the most theoretically advanced version did not perfectly replicate human scoring patterns. Rather than seeing this as a failure, we interpret it as a potential strength. Human observers bring expertise but also biases. AI, when carefully guided by theory, may detect patterns humans overlook. The goal is not to reproduce human judgment exactly, but to provide a complementary, theory-driven perspective.

We were deliberate about the boundaries of the system. GABRIEL does not talk to the child, does not tell parents what to say in the moment, and does not replace human interaction. Scaffolding is deeply relational and emotional. Trust, warmth, and empathy cannot be automated. The AI is positioned as a support for the adult, while the caregiver remains the central developmental partner.

There is also a broader concern that AI may reduce human thinking by automating tasks. Our approach follows a different logic: cognitive augmentation rather than automation. The system does not make parenting easier in a mechanical sense. Instead, it makes reflection more structured and potentially deeper. Parents must interpret feedback, connect it to their lived experience, and decide how to adapt their future interactions. This is a metacognitive process, thinking about one’s own actions and intentions, which can strengthen parental agency. For this reason, we describe the approach as “scaffolding the scaffolder.”

This study demonstrates that it is technically and conceptually possible to translate complex developmental psychology into AI tools that provide reliable, theory-informed reflections for caregivers. The next steps involve studying how parents change their interactions after using such feedback, examining issues of trust and acceptance, testing cultural and algorithmic biases, and comparing AI-generated reflections with those of expert clinicians.

At a broader level, the work contributes to an ongoing societal question. As AI technologies enter homes, will they distract families, or can they help people become more aware, intentional, and connected in their relationships? We argue for a model of AI that does not aim to replace human care, but to help humans see their own interactions more clearly. In this vision, technology does not step into the relationship between parents and children. Instead, it stands beside the caregiver, functioning as a theory-informed mirror that supports more conscious and deliberate engagement.

Follow the Topic

-

Human Arenas

The aim of this journal concerns the interdisciplinary study of higher psychological functions (as topic of a general theory of psyche from the perspective of cultural psychology) in human goal-oriented liminal phenomena in ordinary and extraordinary life conditions.

Introducing: Social Science Matters

Social Science Matters is a campaign from the team at Palgrave Macmillan that aims to increase the visibility and impact of the social sciences

Continue reading announcementRelated Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Arena of Technologies

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Arena of Health

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Ongoing

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in