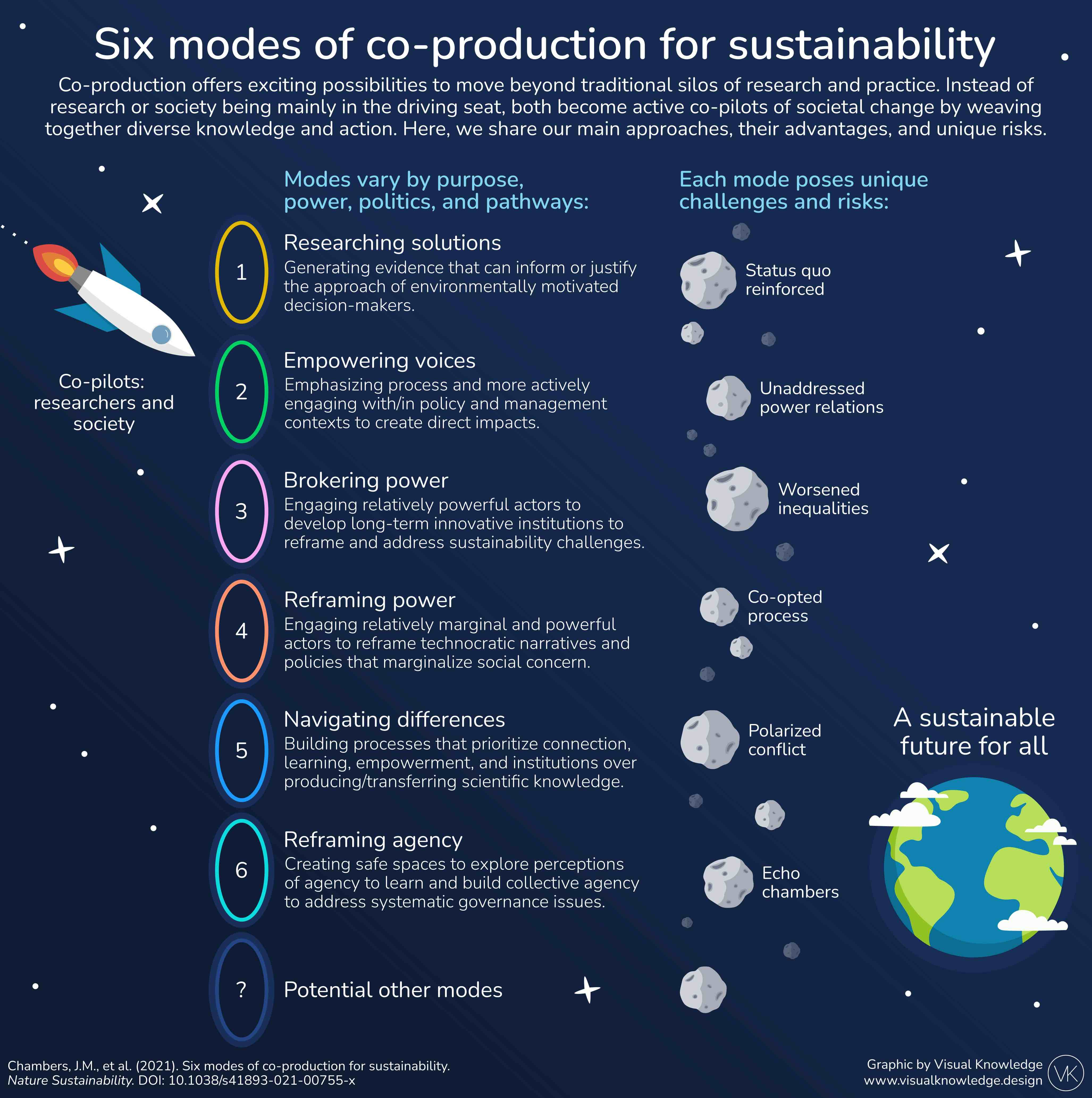

Six modes of co-production for sustainability

Published in Sustainability

Co-production supports diverse people to develop knowledge and action for addressing persistent societal challenges. Yet, little is known about the variety of co-production approaches in use, and their outcomes. To explore this in the realm of sustainability, we embarked on a collaborative multi-year journey that resulted in our new paper: Six modes of co-production for sustainability.

The idea for this paper emerged from two workshops in the US and Mexico, where we brought together diverse researchers and practitioners of co-production to discuss experiences and challenges. I was completing my PhD research at the time, which uncovered a significant gap between conservation and development aims and outcomes in northern Peru. However, I was struggling to connect this knowledge to actual change. When I was approached by the Luc Hoffmann Institute (LHI) to lead an analysis of co-production, I jumped at the opportunity to further explore the topic and rethink my own approach to linking research and action by learning from so many others.

What was originally planned as a 6-month literature review quickly grew into a collaborative multi-year project that connected 42 co-production scientists and practitioners around the world. Instead of limiting ourselves to a specific method, funder, or region, we gathered 32 cases that were as diverse as possible in their practices, contexts, and scales. Taking such a broad view was challenging to analyze, yet it revealed many interesting differences which would have remained hidden from within any particular silo. Yet, our cases had one thing in common. They all aimed to weave research and practice together for the sustainability of ecosystems – working on complex issues such as land and ocean biodiversity loss, wildfires, climate change, and supply chains.

Our analysis was highly collaborative in its design. As the project lead, I had the analytical bird’s-eye view across all cases to identify interesting points of difference, while an expert for each case was heavily involved in critically reflecting on their case. In various workshops, our author team collaboratively interrogated the emerging findings. The result was a long list of ways in which cases differed. Four themes emerged as particularly important for shaping co-production practices and outcomes. In our paper, we call these the ‘four P’s’: the purpose of co-production, understanding of power, approach to politics, and pathways to impact. A cluster analysis based on different approaches to these four aspects revealed that certain cases took similar design choices – what we call six modes of co-production for sustainability.

This process challenged our understandings of what ‘co-production’ is, what it can achieve, and also what it may risk. The learning across our author team has been multi-faceted, and many are already using the heuristic to facilitate more reflexive co-production design. I share three important insights I learned during this study.

First, I became aware of the mode I most often employ, and how I could better manage the risks it entails. I realized that my PhD research was squarely in Mode 4 (reframing power). I valued the autonomy of my research process to take a critical view of interventions and spotlight marginalized perspectives of project impacts. However, I came to realize that it wasn’t just the knowledge that mattered. Rather, the way I produced and explored this knowledge with those holding power to change existing interventions was fundamental to its impact. I learned several important lessons from other projects similarly seeking to challenge technocratic conservation narratives among game farming in South Africa, Colombia's Protected Area Network, and the global network of Large Scale Marine Protected Areas (LSMPAs). They taught me how to share power with intervention proponents while still maintaining a critical and politically attuned research lens, and how to prevent research from being co-opted by others.

Second, reflecting on my aims, I realized the need to step outside of my comfort zone and explore new modes. In particular, I was inspired by how mode 3 (brokering power) managed to create safe dialogue spaces that facilitated reframing of sustainability issues with powerful actors whilst actively developing innovative institutions and governance solutions. Check out the global initiative SeaBOS for an example. I also realized the need to better connect such global scale efforts to grassroots movements led by local and indigenous leaders. Several inspiring initiatives developed long-term partnerships in East Africa, Australia, & in global biodiversity assessment processes to weave together scientific and local/indigenous knowledge to support local solutions and broader policy changes. I was also blown away by the creative methods employed, such as participatory mapping to express diverse cultural relations to the sea, and a range of techniques to reveal people’s sense of their own agency to foster collective agency. Several inspiring examples are further outlined in our recent post: The Hitchhiker’s guide to co-production.

Third, I realized the importance of cultivating a supportive environment within which to do this work. This study taught me the urgent need to co-produce not only knowledge, but also direct action and impact via changed relations, practices, institutions, etc. Yet, many institutions are not supportive of more collaborative approaches to research – often entailing longer and slower timelines, and extra effort that is not rewarded. ‘Good process’ is regarded as an intangible aspect of research that is rarely newsworthy. In my current position at Wageningen University, I have enjoyed moving into mode 6 (reframing agency) by facilitating a university-wide process that aims to explore diverse views on what makes research transformative for society and cultivate an institutional environment to enable such work. The insights from our Nature Sustainability paper have already informed key design choices and spotlighted important risks we are managing, such as the creation of echo chambers that fail to reach beyond ‘the already converted’ in order to influence practice.

Our study has taught me that the design choices behind efforts to connect knowledge and action are anything but apparent. Co-producers all aim to connect knowledge and action, but do so in very different ways, often taking the choices and associated risks for granted. A failure to openly recognize and explore this together can result in many missed opportunities. It can even undermine our intended outcomes for sustainability if we ignore critical risks. We hope that our paper can serve as a useful tool for researchers and societal actors to actively reflect on their design choices when embarking on these critical collaborative processes for sustainability.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Sustainability

This journal publishes significant original research from a broad range of natural, social and engineering fields about sustainability, its policy dimensions and possible solutions.

What are SDG Topics?

An introduction to Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) Topics and their role in highlighting sustainable development research.

Continue reading announcement

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in