SN BEN and SDG 3: A Commentary for World Malaria Day

Published in Microbiology, Biomedical Research, and General & Internal Medicine

Malaria: Background and History

Malaria is a life-threatening disease spread to humans through the bites of female mosquitoes infected with the Plasmodium parasite [WHO Malaria Factsheet]. Malaria is mostly found in tropical countries, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa, where it poses a significant public health challenge. The disease, although life threatening, is preventable and curable and does not spread from person to person.

Symptoms of Malaria

A person bitten by a malaria carrying mosquito may not show any symptoms until 8-15 days after being bitten. Symptoms of the disease can range from mild or severe, with mild symptoms often being mistaken for other illnesses:

- fever,

- chills

- nausea,

- vomiting,

- muscle pain,

- and headache.

As the disease progresses, severe symptoms may develop, severe symptoms include:

- fatigue,

- confusion,

- seizures,

- and difficulty breathing.

Those at high risk of severe infection leading to severe complications and/or death are babies, children under five years, pregnant women and girls, and people with HIV or AIDS.

Overlap with Sickle Cell Disease

Malaria has been affecting human beings for over 5000 years [A Brief History of Malaria], and in that time the human body has developed ways to fight back. Sickle cell disease is a genetic disorder that affects the haemoglobin in red blood cells, causing them to assume a sickle shape [Verywell Health: Sickle Cell and Malaria: What’s the Link?] – think of the farm tool. This abnormal shape can lead to blockages in blood flow and various health complications. Interestingly, there is a significant overlap between regions with high malaria prevalence and those with high rates of sickle cell mutations. Read our previous blog: SDG3: Sickle Cell Disease and its Impact on the Black community to find out more.

The sickle cell trait, where an individual inherits one normal haemoglobin gene and one sickle cell gene, provides a protective advantage against malaria. This is because the sickle-shaped red blood cells are less hospitable to the malaria parasite, slowing their growth, thus reducing the severity of the infection [Medical News Today]. Decreased parasite growth also allows more time for the immune system to react to and destroy the infected red blood cells. This evolutionary adaptation explains the higher prevalence of Sickle Cell in malaria-endemic regions.

Effects on Babies

Malaria poses a severe threat to babies and young children, who are among the most vulnerable to the disease, accounting for a significant proportion of malaria-related deaths globally. According to the World Health Organisation (WHO), children younger than five years accounted for 76% of fatalities due to malaria in 2023 [WHO Malaria Factsheet]. Babies can contract malaria through the bite of an infected mosquito or in the womb from their mothers. Symptoms in babies include high fever, chills, drowsiness, loss of appetite, and rapid breathing. If not treated promptly, malaria can lead to severe complications, and even death.

Diagnosis and Treatment

Fast and accurate diagnosis of malaria is important for effective treatment, especially for young children between ages one and five. When doctors diagnose based on symptoms alone, they often misdiagnose, leading to unnecessary treatments. This not only wastes medicine but can also make malaria parasites resistant to drugs over time.

There are three main ways to test for malaria. The first is by looking at symptoms like fevers and vomiting. WHOs Integrated Management of Children Illness (IMCI) created an algorithm to help doctors diagnose childhood diseases such as malaria based on symptoms, and this has helped improve diagnostic rates. However, many diseases in tropical areas cause similar symptoms, so this method is not reliable.

The second method involves blood tests; the gold standard for malaria diagnosis. A finger prick can provide a sample that’s either checked under a microscope for parasites or used in a rapid diagnostic test (RDT) that detects malaria proteins in minutes without the need for special training. The third and most accurate method is a lab test called PCR (polymerase chain reaction), which can detect even smaller amounts of the parasite and identify the exact malaria species. However, due to its complicated technology, high cost and limited availability, it is not often used.

When it comes to treatment, mild malaria can often be managed at home with antimalarial pills such as chloroquine, along with medicines to manage symptoms (such as paracetamol to bring down fevers). Severe cases need hospital care as soon as possible; especially if the child is unconscious, has trouble breathing, seizures, or extremely low blood sugar. In these situations, doctors use intravenous (IV) artesunate, which works better than drugs like chloroquine (which often fails against African malaria strains due to their resistance against this drug type). If the child has severe anaemia from malaria, they may need a blood transfusion, though milder cases are treated with iron supplements instead.

Preventing malaria is just as important as treating it. The Mosquirix vaccine, approved by WHO in 2021, which is approved for children in sub-Saharan Africa and other areas with high malaria transmission, resulted in a 9% decrease in deaths and 30% decrease in hospital admissions of children with severe malaria. Unfortunately, vaccine immunity is short-lived. The best everyday defences are mosquito nets and insecticides to prevent bites, and draining stagnant water where mosquitoes breed. Scientists are also working on long-term solutions like gene drive, which works by genetically modifying female mosquitoes to make them infertile, thus reducing their numbers. By combining better testing, effective treatment, and smart prevention, we can protect more children from this dangerous disease.

Spreading Awareness

Fortunately, there are charities and organisations dedicated to the funding of research, prevention and eradication of malaria. They provide vaccinations, healthcare, mosquito nets, trainings, programmes and parental education for how to manage malaria if their child contracts it. Among many other initiatives, World Vision and the Malaria Consortium send community health workers to homes infected with malaria so that sufferers do not have to travel far for care.

Malaria No More is a UK based charity, with global offices. They launch campaigns with the endorsement of celebrities such as David Beckham and Zoe Sugg to engage public curiosity to a higher level and spread awareness. Beckham’s campaign Malaria Must Die, So Millions Can Live launched in February 2017, and within two months the campaign reached one billion people, resulting in the discussion of malaria at the Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting that year (see also Zero Malaria Britian more campaigns). Malaria No More also share personal stories – the retelling of these real-life stories is immediate and powerful, connecting with our emotions and encouraging us to listen and take action.

The Against Malaria Foundation primarily fundraises for mosquito nets for families in malaria-endemic areas. As I am writing this, on the 11th of April 2025, they have raised $751,074,615, funded 340,859,437 nets and have protected 613,546,987 people from malaria, and counting. Their main fundraising event is Swim Against Malaria. Events like these, or bake sales, quizzes, sponsored silences, walks and marathons, ‘dress down days’ at work or ‘mufti days’ at school, are other great activities to fundraise for malaria, or for any charity of your choice. Celebrating WHOs World Malaria Day on April 25th is a fantastic opportunity to collaborate on these initiatives.

At Springer Nature we proudly contribute to malaria research by publishing the innovative work of our authors. Examples of our broader-scope journals which publish malaria-based content include Nature Immunology and BMC Infectious Diseases of Poverty. At BMC, we have our very own Malaria Journal dedicated to publishing only malaria-based research. Malaria Journal launches Collections (or ‘Special Issues’) which target specific topics within the field to share with their readers, such as: The RTS,S/AS01 Malaria Vaccine Implementation Programme in Ghana, Kenya and Malawi. Collections increase community engagement, visibility and research output in a niche area – in this case, focussing on the distribution of malaria vaccinations to African countries. Springer Nature also promotes research via our Research Communities website; the channel BugBitten is dedicated to the study of malaria and other infectious diseases.

As an organiser of Springer Nature’s Black Employee Network (SN BEN), I love introducing our members to cultural exhibitions and events, which speak to our identities and connect us to our cultures, ancestries and heritages. This April, we visited the Hard Graft: Work, Health and Rights exhibition at the Wellcome Collection, where we discovered how creatives campaign against malaria through art.

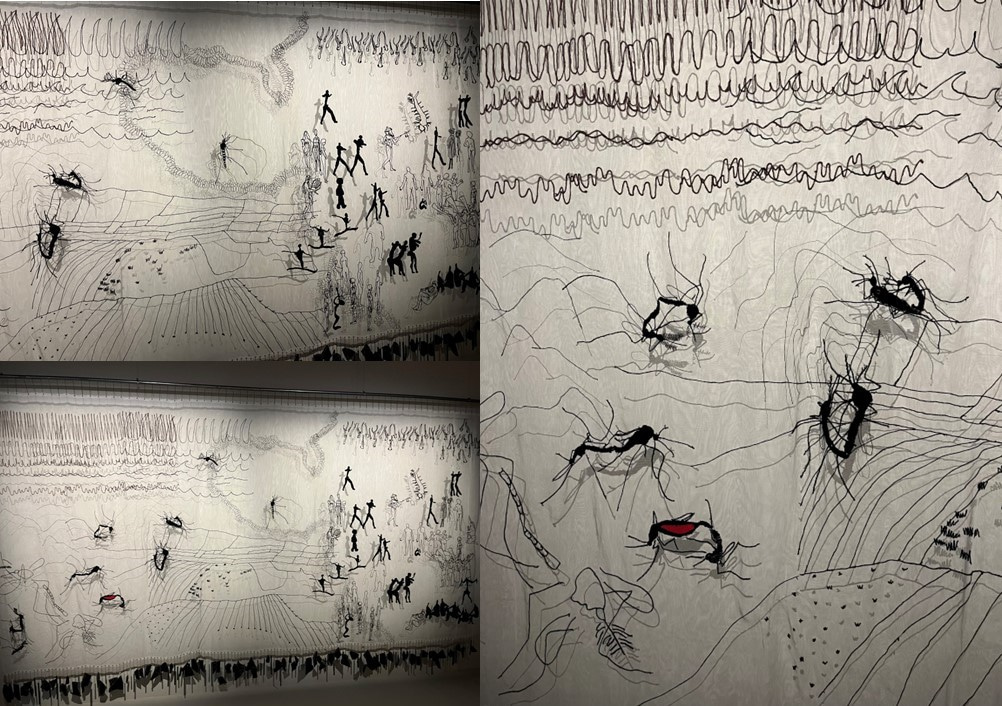

In her artwork Mosquito Shrine, Vivian Caccuri uses mosquito nets, cotton thread, slate and aluminium to portray mosquitoes and humans comparatively, highlighting the spread of infectious diseases through the literal medium used to prevent them (Figure 1). The same exhibition presents an assortment of postage stamps from 1962-63 – from Nigeria, to Sierra Leone, to Dubai – promoting WHO’s Global Malaria Eradication Programme (Figure 2). Here we are, 62 years on, still looking for the same answers to end malaria.

Through our ignorance and misunderstanding of diseases such as malaria, we are perpetuating the cycle of racial and systemic poverty. The failure to protect children and young people from Black and ethnic minority backgrounds from diseases like malaria, is not only impacting on health but also on education, work, relationships and community infrastructure. I’d like to leave you with this: how can you make a difference and support the prevention and eradication of malaria? How can you help change the world?

Figure 1: Mosquito Shrine, Vivian Concurri, 2018. Wellcome Collection, 2025.

Figure 2: Postage stamps promoting the World Health Organisation's Global Malaria Eradication Programme, 1962-63. Wellcome Collection, 2025.

References:

- Abdoulaye Diabaté. “How to end malaria once and for all”, TEDtalks, April 2024, https://www.ted.com/talks/abdoulaye_diabate_how_to_end_malaria_once_and_for_all?language=en

- Amir, Amirah et al. “Diagnostic tools in childhood malaria.” Parasites & vectors vol. 11,1 53. 23 Jan. 2018, doi:10.1186/s13071-018-2617-y

- Arrow KJ, Panosian C, Gelband H, editors. Institute of Medicine (US) Committee on the Economics of Antimalarial Drugs; Saving Lives, Buying Time: Economics of Malaria Drugs in an Age of Resistance. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2004. 5, A Brief History of Malaria. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK215638

- Parang N Mehta, Russell W Steele. “Pediatric Malaria Treatment & Management”, Medscape, 19 July 2024, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/998942-treatment

- Parang N Mehta, Russell W Steele. “Pediatric Malaria Medication”, Medscape, 19 July 2024, https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/998942-medication

- Tangpukdee, Noppadon et al. “Malaria diagnosis: a brief review.” The Korean journal of parasitology vol. 47,2 (2009): 93-102. doi:10.3347/kjp.2009.47.2.93

- World Health Organization Factsheet: Malaria, 11 December 2024: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/malaria

- Very well Health: Sickle Cell and Malaria: What’s the Link?, 23 August 2024: https://www.verywellhealth.com/sickle-cell-and-malaria-5323165

This project was developed and edited by India Sapsed-Foster, Associate Publisher. 'Malaria: Background and History' authored by Abiola Lawal, Senior Publisher. 'Diagnosis and Treatment' written by Kesiena Okumagba, BSc Physics student at the University of Kent. 'Spreading Awareness' created by India Sapsed-Foster.

Follow the Topic

-

Malaria Journal

This journal is aimed at the scientific community interested in malaria in its broadest sense.

-

BugBitten

A blog for the parasitology and vector biology community.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Elimination of infectious diseases of poverty as a key contribution to achieving the SDGs

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Ongoing

AI for Malaria Elimination: Data-Driven Innovations in Surveillance and Control

As malaria-endemic regions continue to generate vast and complex datasets—from epidemiological surveillance and vector control to genomic sequencing and intervention outcomes—the need for robust, scalable, and intelligent data management systems has never been more urgent. This collection explores the transformative impact of Artificial Intelligence (AI) on managing, integrating, and interpreting malaria-related data to support research, policy, and public health action.

While AI applications in diagnostics have received considerable attention, this collection shifts the focus to underexplored areas such as:

-Data harmonization and integration across varied sources (e.g., clinical, entomological, environmental, genomic, geospatial, intervention efficacy studies, socioeconomic, and surveillance

-Predictive modeling and decision support systems for malaria control and elimination strategies

-AI-driven tools for real-time surveillance, outbreak detection, and resource allocation

-Ethical, governance, and equity considerations in the deployment of AI for malaria data management

-Infrastructure and capacity-building for sustainable AI adoption in low-resource settings

We welcome original research, case studies, reviews, and methodological papers that demonstrate innovative uses of AI to enhance the quality, accessibility, and utility of malaria data. Contributions that address challenges in data interoperability, bias mitigation, and community engagement are especially encouraged.

This collection aims to foster interdisciplinary dialogue and highlight scalable solutions that can accelerate progress toward malaria elimination through more innovative data practices.

This Collection supports and amplifies research related to SDG 3, Good Health and Well-Being.

All submissions in this collection undergo the journal’s standard peer review process. As an open access publication, this journal levies an article processing fee (details here). We recognize that many key stakeholders may not have access to such resources and are committed to supporting participation in this issue wherever resources are a barrier. For more information about what support may be available, please visit OA funding and support, or email OAfundingpolicy@springernature.com or the Editor-in-Chief.

Publishing Model: Open Access

Deadline: Aug 11, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in