Stellar wind of old stars reveals existence of a partner

Published in Astronomy

Humans don’t live long enough to realise it, but stars are also born, they age, and they die. It's a process that takes billions of years. As a star gets older, it becomes bigger, colder, and redder – hence the name ‘red giants’. Our sun will also become such a red giant in four and a half billion years.

In the final stage of their life, red giants eject their mass – gas and other matter – in the form of a stellar wind. Earlier observations confirmed that red giants lose a lot of mass this way. Twelve mass-loss rate record holders, in particular, have been baffling scientists for decades. These red giants supposedly eject the equivalent of 100 earths per year for 100 to 2,000 years on end. Even astronomically speaking, that's a lot of matter in a short amount of time. This behaviour was difficult to explain: If you look at the mass of such a star in the next phase of its life, the intense stellar wind doesn't last long enough to account for the mass loss that we’ve seen. It was also statistically improbable that we had discovered twelve of these red giants, knowing that what we were seeing was a phase that lasted only hundreds or thousands of years compared with their billion-year-long life. It's like finding a needle in a haystack twelve times.

In order to (potentially) resolve this decades-old conundrum, we decided to look at two of these red giant stars with the ALMA observatory in Chile. ALMA is the largest ground-based observatory in the world, an interferometer consisting of 66 telescopes which can observe electromagnetic radiation at millimetre and submillimetre wavelengths. The array has been constructed on the 5 000 m elevation Chajnantor plateau. This location was chosen for its high elevation and low humidity, factors which are crucial to reduce noise and decrease signal attenuation due to Earth's atmosphere. ALMA is operational as of 2011.

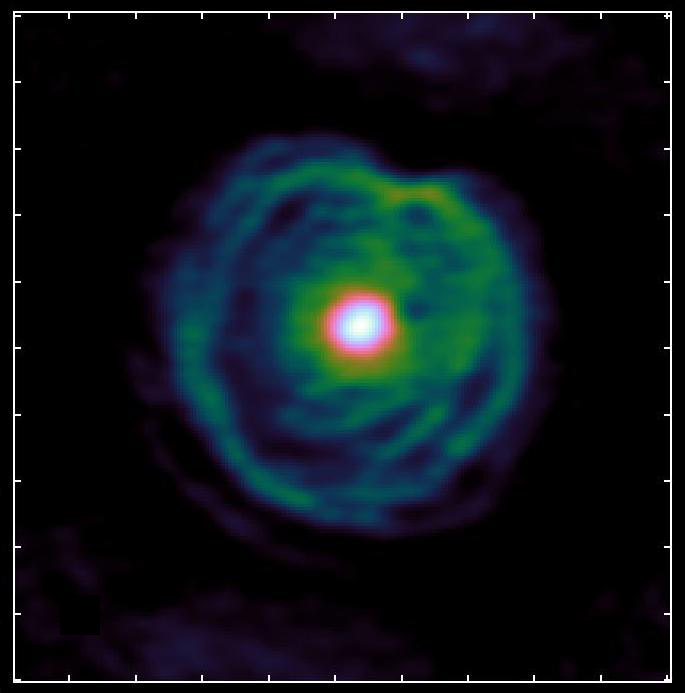

After receiving and reducing the ALMA data, we almost immediately realized what was happening with these two red giants. The first thing that we noticed in the ALMA data was that the wind of both stars forms a spiral. This is an indirect indication that the red giants are not alone, but part of a binary star system. The red giant is the main star with a second star circling it. Both stars affect each other and their environment gravitationally in two ways: on the one hand, the stellar wind is pulled in the direction of the second star and, on the other hand, the red giant itself also wiggles slightly. These movements give the stellar wind a spiral shape.

The discovery of a partner star made everything fall into place. We believed that these red giants were record holders for mass-loss rate, but that’s not the case. It only seemed as though they were losing a lot of mass because there’s an area between the two stars where the stellar wind is much more concentrated due to the gravity of the second star. These red giants don’t lose the equivalent of 100 earths per year, but rather 10 of them – just like the regular red giants. As such, they also die a bit more slowly than we first assumed. To rephrase in a positive way: these old stars live longer than we thought. We are now investigating whether a system with a binary star could also be the explanation for other special red giants. We believed that many stars lived alone, but we will probably have to adjust this idea. A star with a partner is likely to be more common than we thought.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Astronomy

This journal welcomes research across astronomy, astrophysics and planetary science, with the aim of fostering closer interaction between the researchers in each of these areas.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in