Strontium isotopes reveal habitat preferences of fossil herbivores in Malawi

Published in Ecology & Evolution and Arts & Humanities

Paleoecologists often use the behavior of modern animals as an analogue for the behavior of fossil individuals of the same species, or of a closely related taxon. These assumptions are justified under the principle of actualism (or uniformitarianism), which posits that the present is "key" to understanding the past. Unfortunately, it turns out that animals, even in the recent past, can behave in ways that are quite different from what we can observe today. Some biogeochemical methods allow us to to catch a glimpse of how these individuals actually behaved.

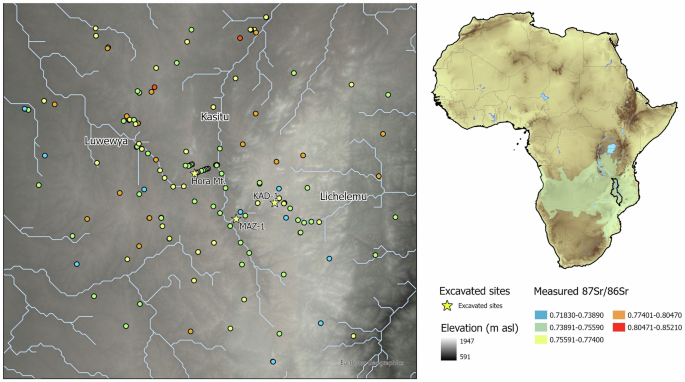

I am part of a team (the Malawi Ancient Lifeways And Peoples Project, or MALAPP, led by Dr. Jessica Thompson, Yale University) that has been investigating hunter-gatherer archaeological sites in the Mzimba district of Malawi since 2016. Many of the animal bones found in these sites belong to large, gregarious grass-eaters, or grazers, such as the zebra and the wildebeest. Today, much of the land in our study area is cultivated, so we cannot observe these same animals to make assumptions about their behaviors and habitats.

The non-cultivated parts of the study area are mostly characterized by open woodland with sparse seasonal grasses. Modern year-round grasslands are limited to two main habitat types: grasslands along rivers and other sources of water, and grasslands in the mountains. The latter are a component of a unique, discontinuous bioregion called the Afromontane region, which is a critical biodiversity hotspot comprising evergreen forests and grasslands. These grassy habitats are relatively limited in extension, so do all these fossil grazers indicate that grasslands were more extensive in the past?

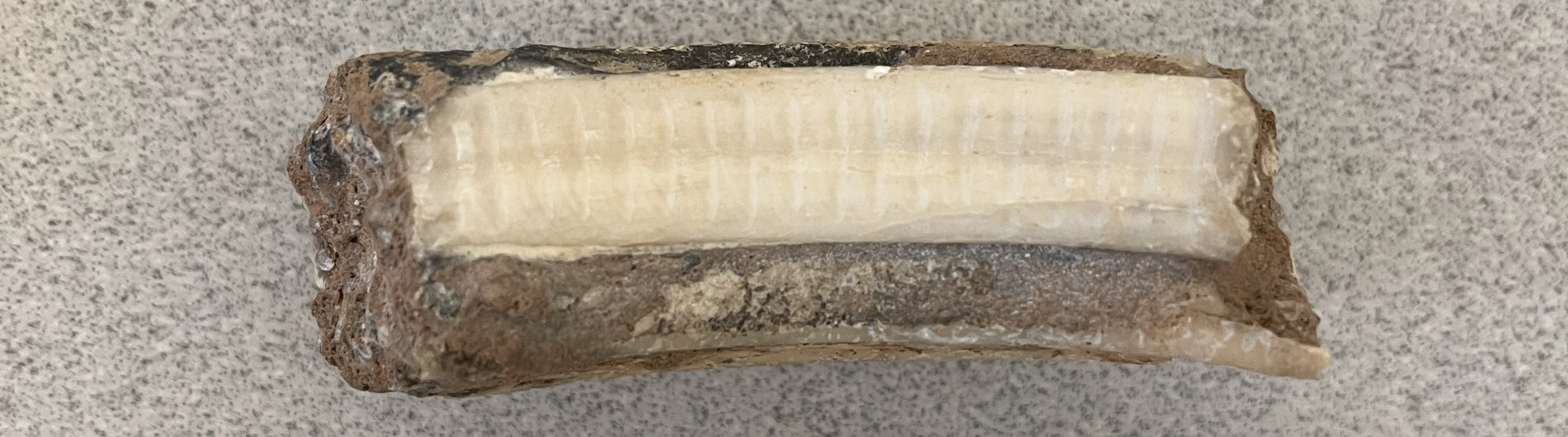

To find out, we decided to use strontium isotopes - namely the ratio of radiogenic strontium-87 to strontium-86. This ratio depends on geological substrate and is incorporated in the bodies of organisms through food and water, thus acting as a "fingerprint" for provenience.

First we needed a map of how strontium isotopes vary across the study area. We call that an "isoscape". To build one, we collected plants from different parts of the study area (just over 2500 square km) and measured strontium isotopes in them, then used spatial interpolation to create the isoscape. We then measured strontium isotopes in fossil teeth and used these values to find matches in the isoscape for likely areas of provenience.

The results show that large grazers grew up in riparian and Afromontane habitats; the same habitats that are grassy today and did not move away across the year. Why does this matter? There are two implications. The first one is anthropological. If these highly-prized prey animals were always available in highly localized parts of the landscape, then ancient hunters could procure them quite reliably and predictably. Across traditional societies, this resource structure favors territorial behavior (whereas disperse and unpredictable resources favors inter-group cooperation to buffer the risk of shortfalls). The second implication is about conservation. We often think that to preserve grazers population whose migratory routes are being disrupted we need to protect migratory "corridors", for instance by limiting fences along the way. However, some populations did not migrate even before fencing and competition with livestock, so it is important to figure out what factors promote different movement patterns, including year-round residence.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in