Ten-year pursuit of a dream: exploring the mystery of flexistyly

Published in Ecology & Evolution, Genetics & Genomics, and Plant Science

A fascinating sexual system in plants

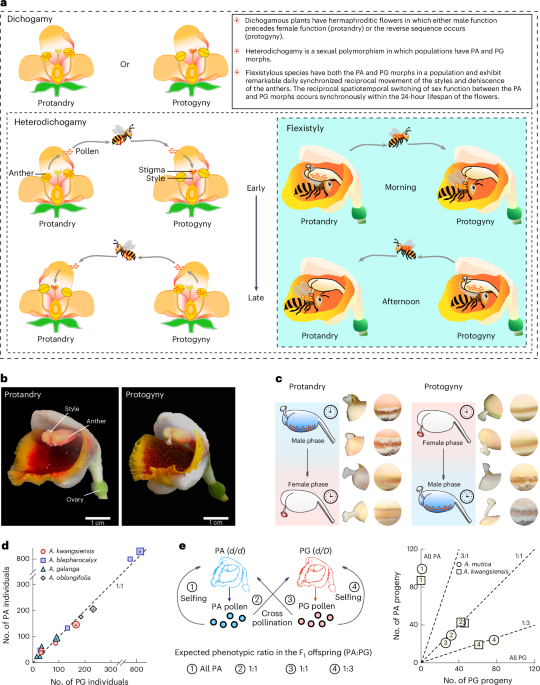

The differentiation of sexual function in hermaphroditic plants is the main pattern of sexual reproductive system diversity. The mechanism controlling the differentiation of sexual function in plants is complicated, extremely challenging and fascinated. Although many studies have revealed the genetic mechanism of several mating strategies, such as dioecy and heterostyly, the genetic mechanism of the widespread cross-pollination strategy—dichogamy is largely unknown. Most dichogamous species are either fixed for protandry (mature male function ahead of female function) or protogyny (mature female function ahead of male function), which creates obstacles to disentangling the genetics of dichogamy. There is a lack of a deep understanding of the genetics of dichogamy, restricting our understanding on the evolution of sexual diversity in plants.

Flexistyly, a special form of heterodichogamy (a type of dichogamy), is a unique dichogamy in the ginger family (Zingiberaceae) reported by Qing-Jun Li et al. in Nature (Li et al. Nature 410: 22). There are two morphs in the flexistylous population with a 1:1 ratio: one morph is protogynous or anaflexistyly, and the other is protandrous or catafexistyly. In the morning, protogynous individuals present female functions with downward stigma (on the passage of pollinator visitation as the recipient of pollen) and closed anthers. Moreover, protandrous individuals play male functions, with upward stigmas (far from pollinator visitation) and dehiscent anthers (donor of pollen). In the afternoon, the role of the sexual functions of protogynous individuals and protandrous individuals is reversed: protogynous individuals play a male function, and protandrous individuals play a female function. This is a marvelous mating strategy for promoting outcrossing and avoiding selfing and male‒female functional interference. Thus, flexistylous species provide an optimal model for investigating the genetics of dichogamy. (Videos of flexistyly: https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1038%2Fs41477-025-02125-3/MediaObjects/41477_2025_2125_MOESM3_ESM.mov and https://static-content.springer.com/esm/art%3A10.1038%2Fs41477-025-02125-3/MediaObjects/41477_2025_2125_MOESM4_ESM.mov.)

A long journal for decoding the mystery of flexistyly

Since the report of flexistyly in nature, many studies have been conducted to probe the ecological, physiological, and evolutionary significance of flexistyly. In addition, although studies of molecular mechanisms have been carried out via different methods for many years, the key genes involved are difficult to identify. This seemed to be an unattainable dream of Qing-Jun Li. With the development of sequencing and corresponding data analysis, we have a good opportunity to explore the deep background of flexistyly. Subsequently, Qing-Jun Li organized a research group composed of different experts approximately 2016 to attempt to uncover the mystery of flexistyly. We then set off on a long journey, cooperated closely, and contributed our wisdom and ability to our common dream.

We first investigated the morph ratio of PG:PA in natural populations of several Alpinia species. Moreover, pollination experiments were also conducted between and within the two morphs. In the wild, selfing is almost impossible. The results clearly revealed a PG:PA ratio of 1:1 in natural populations. Interestingly, F1 offspring resulting from cross-pollination between morphs yielded a PG:PA ratio of 1:1. F1 offspring self-pollinated with PA produced only PA, and those self-pollinated with PG produced both morphs with a PG:PA ratio of 3:1. These results explicitly revealed that morphs of flexistyly conferred Mendelian inheritance. In this system, PG is heterozygous for the dominant allele (d/D; D for dichogamy), and PA is homozygous for a recessive allele (d/d).

Fortunately, we then identified a dichogamy-determining region (DDR) in chromosome 8 via a GWAS. A comparison of the genomes of PG and PA indicated that the DDR exhibited a hemizygous structure in which PG has a large insertion containing an intact LTR compared with the genome of PA. There are seven genes in the DDR. Initially, we focused on the known gene Cold-Regulated Gene 27/28 (COR27/28) because this gene has been validated to be a key regulator of the circadian clock and is regulated by temperature and light signals. These anticipated functions seemed to fit the daily dynamics of flexistyly. However, COR27/28 is a pseudogene in PA. At this stage, we had to shift our focus to other genes associated with the DDR region. Since DDR is located in the 5′ UTR of the SMPED1 gene, we turned our attention to SMPED1 itself. Meanwhile, we verified the expression pattern and function of SMPED1 in Alpinia species as well as other genes in the DDR within a day under natural illumination and continuous illumination. During the experiment under continuous illumination, we surprisingly found that the sexual functions of PA were converted to the sexual functions of PG. The exciting finding was that only SMPED1 exhibited the expected rhythmic expression matched with the behaviors of style and anther under both natural and continuous illumination.

However, how to validate the function of SMPED1 in nonmodel Alpinia species such as a “enormous mountain” has hindered our progress for several years. We first wanted to construct a transgenic regeneration system for Alpinia species. Callus induction and redifferentiation were the primary challenges. Although we have spent several years and successfully induced calli in Alpinia mutica, a transgenic regeneration system based on calli has been difficult to achieve until now. In addition to callus culture, other methods aimed at constructing a transgenic regeneration system for Alpinia species have been explored. All ended in failure. Fortunately, the use of the antisense oligodeoxyribonucleotide (AS-ODN) technique could be used to validate the function of SMPED1 in Alpinia species. On the basis of the coding sequence of SMPED1, we selected an effective AS-ODN that can reduce the expression of SMPED1 in Alpinia mutica. Under the effective AS-ODN treatment, the style movement of Alpinia mutica almost stopped. This result inspired us to confirm that rhythmic movement of style, or female function, was directly controlled by SMPED1. However, the rhythm of the anthers did not change under the AS-ODN treatments. This may be caused by an impermeable secondary cell wall on the anther preventing the penetration of the AS-ODN.

We therefore employed Arabidopsis thaliana to validate the function of SMPED1. Initially, we encountered a problem: when we aligned the CDS sequence of SMPED1 against public databases, no homologous genes were identified, leaving us puzzled. During this prolonged period of uncertainty, an accidental insight prompted us to search the protein sequence of SMPED1 against nucleotide databases. The search revealed that homologous proteins do exist in other plant species, including the model plant Arabidopsis thaliana. In A. thaliana, two SMPED1-like proteins—AtSMPED1 and AtSMPED2—were identified, and bioinformatic analysis of their gene expression indicated high levels in pollen. This discovery greatly encouraged us and suggested that SMPED1 was likely the key gene we had been seeking. Consequently, we generated transgenic Arabidopsis lines that overexpression and knockdown of AmSMPED1, AtSMPED1, and AtSMPED2 under the control of the 35S promoter. The overexpression and knockdown of AtSMPED1 and AtSMPED2 can promote and delay the dehiscence of anthers, respectively. The overexpression of AmSMPED1 in A. thaliana can also promote the dehiscence of anthers. Although this is a very difficult process because we have to work continuously for 24 h, the results provided strong evidence that SMPED1 was the critical gene that we have been searching for a long time. Thus, we clearly stated that SMPED1, as a pleiotropic gene, “controls the fundamental reproductive behaviors of both male and female organs simultaneously.”

It was interesting that there was only one synonymous mutation in the coding region of SMPED1 between PA and PG. This finding suggested that the rhythmic expression of SMPED1 could be regulated by the promoter, a cis-regulatory element. Our experiments validated that the activities of the promoters were significantly different between PA and PG.

Because flexistyly is not present in all the species in Zingiberaceae, further questions remained that how and when intraspecific sexual dimorphism occurred in Alpinia. Evolutionary genomics suggested that the formation of PG was induced by LTR insertion, which occurred approximately 4.06 million years ago. We also collected data from 281 genomes to explore the evolution of SMPED1 in angiosperms. These results suggested the evolutionary and structural conservation of SMPED1 across angiosperms, indicating that SMPED1 plays a key role in the reproductive biology of diverse angiosperms.

In general, this study revealed a novel gene at a Mendelian locus that promotes autonomous outcrossing in dichogamy. Our findings innovated our knowledge on the origin and evolution of sexual diversity in plants, despite many remaining questions waiting to be answered. The conservation of SMPED1 in angiosperms suggested that this gene plays an important role in mating time in angiosperms, which could provide a candidate site for crop breeding.

It has been a journey of approximately ten years from the beginning to this publication. This is a cooperative achievement that integrates the painstaking effort of every participant. Many thanks to every coauthor and those people who helped us. Sadly, Qing-Jun Li passed away on December 1, 2022, just as we were nearing a breakthrough. The publication of this paper achieved a dream and serves as a tribute to Qing-Jun Li’s memory.

If you are interested in more details about the story, please read our paper “Jian-Li Zhao*#, Yang Dong#, Ao-Dan Huang#, Sheng-Chang Duan#, Xiao-Chang Peng#, Hong Liao, Jiang-Hua Chen, Yin-Ling Luo, Qin-Ying Lan, Ya-Li Wang, Wen-Jing Wang, Xin-Meng Zhu, Pei-Wen Luo, Xue Xia, Bo Li, W. John Kress, Jia-Jia Han*, Spencer C. H. Barrett*, Wei Chen* & Qing-Jun Li. Ginger genome reveals the SMPED1 gene causing sex-phase synchrony and outcrossing in a flowering plant” published in Nature Plants on 07 October, 2025 (https://doi.org/10.1038/s41477-025-02125-3). You can also read this Chinese blog for a more interesting story behind this paper: https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/3VzFCycea6o1OhJAxqARNw.

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Plants

An online-only, monthly journal publishing the best research on plants — from their evolution, development, metabolism and environmental interactions to their societal significance.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in