The aquarium shop discovery

Published in Ecology & Evolution and Agricultural & Food Science

An unexpected lead

Every research story begins somewhere. Ours started with a simple question: where could we find a piece of mangrove wood? At the time, we were studying mangrove species and needed reference material for microscopic comparison. Someone suggested an unexpected source, the local aquarium shop, where mangrove roots are often sold as decoration for aquaria. It sounded improbable, but curiosity won. I went.

The shop was dimly lit, filled with tanks, filters, and a shelf of twisted wood. Labels promised exotic origins: “honeycomb wood,” “spider root,” “mangrove.” The pieces were beautiful, sculptural forms seemingly shaped by water and time. I chose one labelled “mangrove” and brought it back to the laboratory, convinced that the adventure would not end there. It did not.

Microscopy and revelation

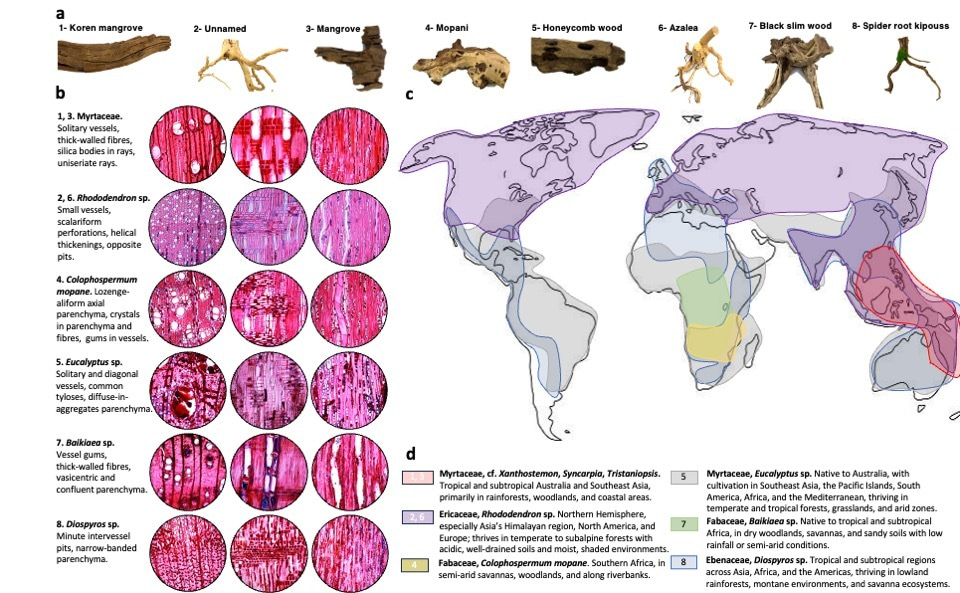

Under the lens, the surprise was immediate. The cell arrangement did not match mangrove wood anatomy. What we had was a completely different species, sold under a familiar name. I believe the misidentification was not malicious. It was likely born from trade habits, where visual resemblance substitutes for botanical accuracy.

Intrigued, I decided to visit another aquarium shop, one that was way better stocked. This time I bought several samples, each labelled as a different type of decorative wood. Back in the lab, the microscope revealed a miniature atlas of the world’s forests: tropical hardwoods, temperate species, woods from Africa, Asia, and South America. Almost every piece was mislabelled. The aquarium trade had unintentionally become a small-scale global timber market.

From observation to publication

That unexpected discovery became the starting point of our study, recently published in Forests (Crivellaro et al., 2025). We documented the diversity of aquarium and ornamental woods, identified species through microscopy, and analysed the implications for trade and consumer awareness. The findings were both fascinating and concerning. Behind the appealing labels lay a web of untraceable origins, inconsistent naming, and potential conservation issues.

The project was not planned, but it captured the essence of scientific curiosity, seeing something ordinary and asking what lies beneath. It reminded me that meaningful research often begins with noticing, not with designing.

Lessons from curiosity

That first visit to the aquarium shop taught me more than I expected. It showed how knowledge can emerge from places far from the laboratory or the field. It reminded me that curiosity is a scientific instrument as powerful as any microscope.

A casual detour became a published study, and a piece of decorative wood became a story about biodiversity, trade, and truth in labelling. Sometimes, science starts not with a grant proposal, but with the simple act of wondering what we are really looking at.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in