The challenging life of Miocene corals

Published in Earth & Environment and Ecology & Evolution

Why do we study fossil corals ̶ and what makes it difficult?

Tropical coral reefs are among the most impacted ecosystems by climate change, with global warming and ocean acidification driven by carbon dioxide emissions threatening their future. These changes in the environment leave distinct fingerprints in the skeleton of corals, allowing scientists to reconstruct past environmental and climate conditions. While the skeletons of modern corals – some living for up to hundreds of years – provide information prior to the beginning of instrumental observations, fossil corals can extend this window deep into Earth’s past. However, finding suitable fossil material is a major challenge because coral skeletons are made of porous aragonite – an unstable form of limestone – that typically alters soon after the coral die. Unaltered fossil specimens are exceedingly rare.

However, exceptions do exist!

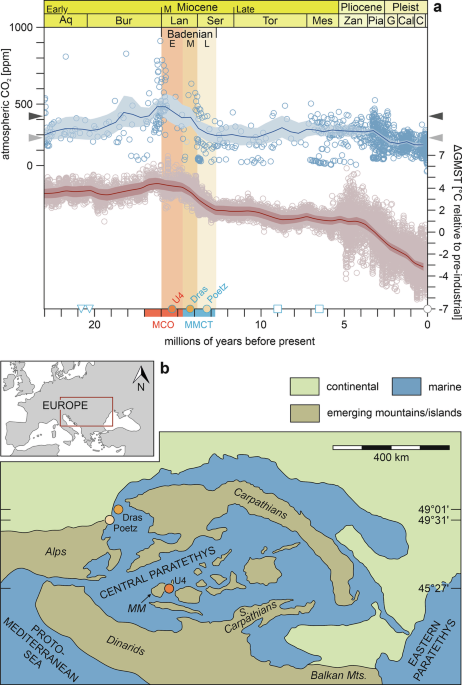

In the collection of the Natural History Museum Vienna, we made the exciting discovery of exceptionally well-preserved Porites corals dating back 13 to 16 million years. Remarkably, these fossil corals retained intact their original aragonite mineralogy, microstructure and porosity of the skeleton, making it possible to access them as archive for paleoenvironmental influences on coral growth. Besides their remarkable preservation, the coral fossils are interesting for three other reasons. Firstly, Porites is today a widely distributed coral and an important reef builder. It serves as a preferred model organism for paleoclimate and coral growth studies, allowing us to make direct comparisons with modern corals. Secondly, the fossils come from a climatic period of great scientific importance, known as the Miocene Climatic Optimum. During this time, global temperatures were highly elevated and atmospheric carbon dioxide levels like those expected in the near future. This makes a useful analog for understanding how corals and their ecosystems could be affected in a warmer, high carbon dioxide world. Thirdly, the corals lived at a high paleolatitude of 45 to 49°N. By contrast, the world's northernmost coral reefs are currently located in Japan at 34°N latitude. Such past coral range expansions have led to the suggestion that high-latitude seas may function as climate change refugia for tropical corals that offer protection from the impacts of warming waters and serve as a long term-buffer against declining coral diversity.

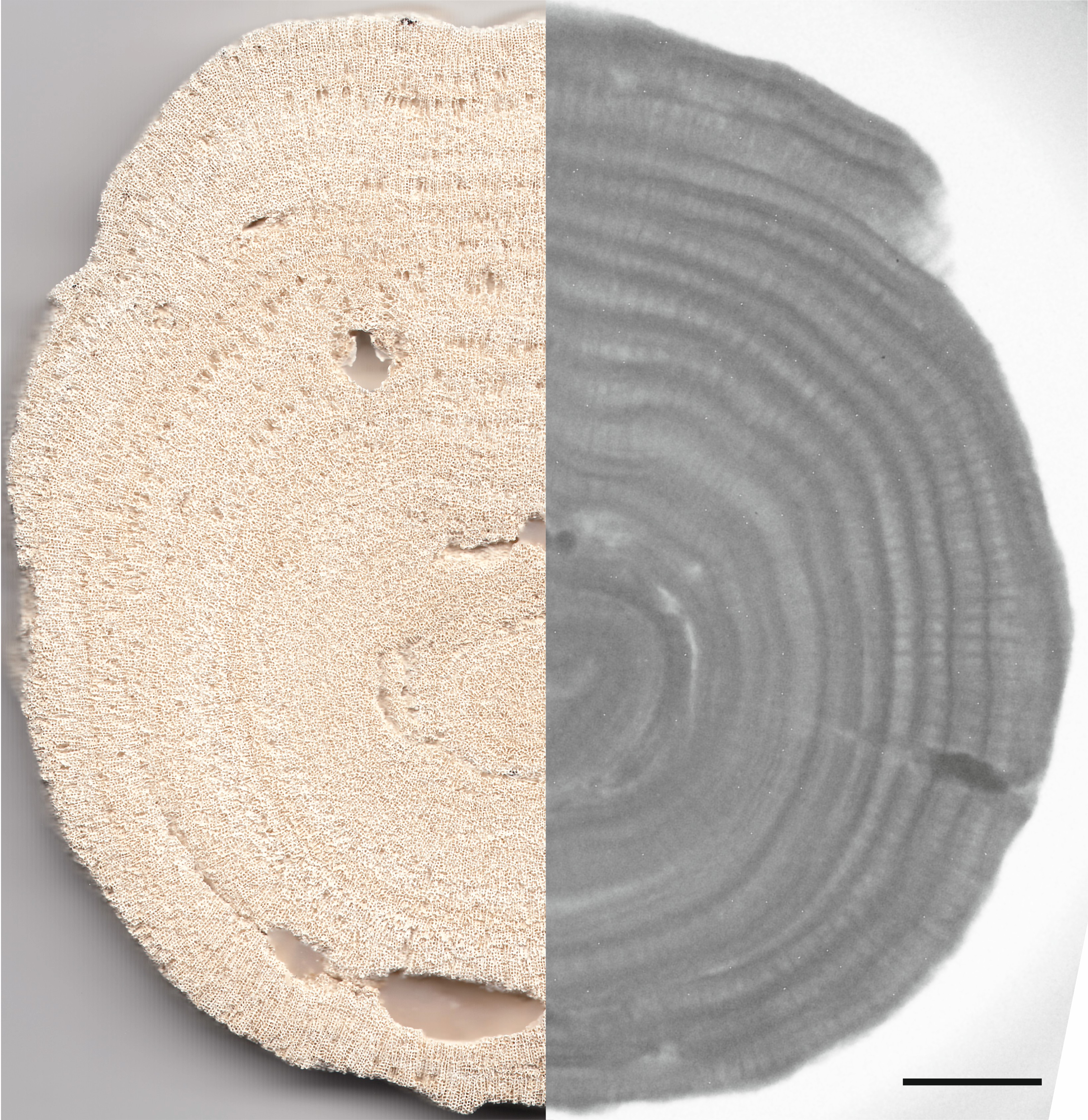

Miocene Porites corallith (rolling coral) in cross section (left) and X-ray image (right). In the X-ray image, alternating light and dark bands can be seen. These bands represent seasonal density differences in the coral skeleton, similar to the growth rings in trees. One light and one dark (denser) band together represent one year. The scale bar is one centimeter.

Unlocking million-year-old secrets

The coral fossils analysed by our research team were collected for their distinctive light coloration and low weight over a century ago. We became interested in them for the same reasons nearly 20 years back, when we started to explore the potential of million-year-old coral fossils for reconstructing past environments. Due to the fragility of the fossil material and the very low growth rates of the corals, we initially faced technical challenges in unlocking these coral archives. To overcome these difficulties, we employed non-destructive X-ray imaging to characterize growth bands and used advanced mass spectrometry to analyze the skeleton’s chemical composition. This allowed us to resolve environmental and physiological signals on seasonal timescales — an unprecedented level of detail for coral fossils this old. The chemical analyses focused on multiple geochemical proxies: the strontium to calcium ratio and oxygen isotopes, both indicators of seawater temperature, the boron to calcium ratio, which is sensitive to the carbonate saturation state of the corals’ internal calcifying fluid, and carbon isotopes to infer the coral nutrition and the functioning of the coral symbiosis.

Not everything was better in the past

The reconstructed seasonal patterns of coral growth and geochemical proxies align closely with what we see in today's Porites corals. This hints that Miocene Porites responded similarly to environmental changes as their modern counterparts. However, the absolute values differ due to variations in environmental conditions. We noticed that the fossil corals had lower calcification rates compared to modern Porites due to slower growth and lower skeletal density. Our multi-proxy study revealed that this slower growth was associated with higher global temperatures and large seasonal sea surface temperature fluctuations of about 10 to 11 °C. The increased global temperatures led to summer conditions in the high-latitude coral habitat that exceeded the critical threshold for coral growth, while winter temperatures neared the lower limit. For the first time in Earth's history, we could identify a possible coral bleaching event caused by summer heat stress through geochemical signatures and growth patterns of a fossil reef coral. We found that low skeletal density resulted from limited calcium carbonate availability for building skeletons, likely due to ocean acidification. Our evidence shows that Miocene corals were able to actively regulate the composition of their calcifying fluid to mitigate the effects of ocean acidification. However, the combination of stress by seasonal temperature changes and ocean acidification pushed them to their limits of resilience.

Follow the Topic

-

Communications Earth & Environment

An open access journal from Nature Portfolio that publishes high-quality research, reviews and commentary in the Earth, environmental and planetary sciences.

Related Collections

With Collections, you can get published faster and increase your visibility.

Archaeology & Environment

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Drought

Publishing Model: Hybrid

Deadline: Mar 31, 2026

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in