The decreasing housing utilization efficiency in China’s cities

Published in Earth & Environment and Sustainability

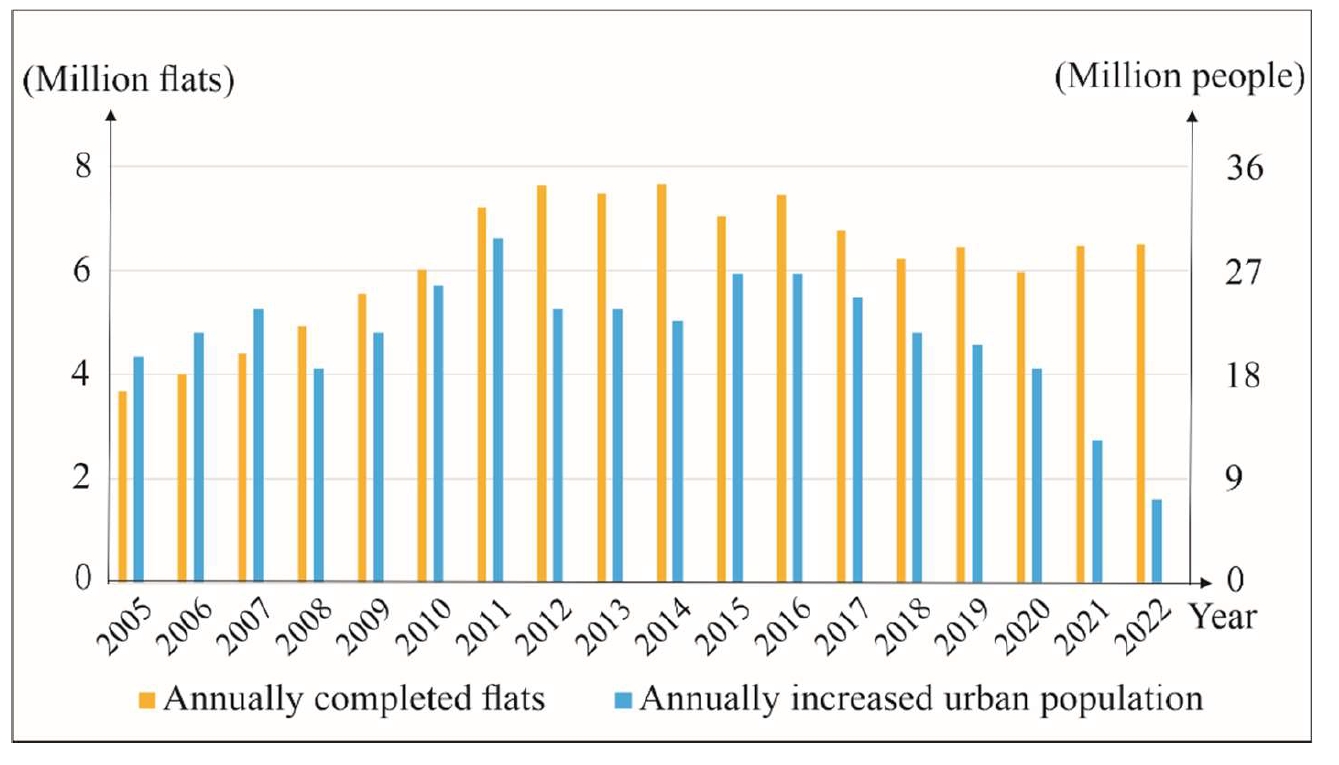

During China’s highly dynamic urbanization process overprovision of housing has created a unique phenomenon commonly referred to as 'ghost cities'. In some cases, entire cities or neighborhoods were virtually empty or were home to far fewer people than would have been possible. This phenomenon gained widespread media attention around the year 2010 and continued to attract attention throughout the following decade. Statistical data from the National Bureau of Statistics of China show that 7.4 million new urban flats were built annually between 2011 and 2016. Although this figure declined, an average of 6.4 million new flats were still constructed each year from 2017 to 2021 (Figure 1). Compared to the annually increasing urban population during the same period, preliminary estimates suggest that the annual oversupply of newly built urban housing rose from 10% to 20% after 2011.

Figure 1. A comparison of annually completed flats and the annual urban population growth in China from 2005 to 2022.

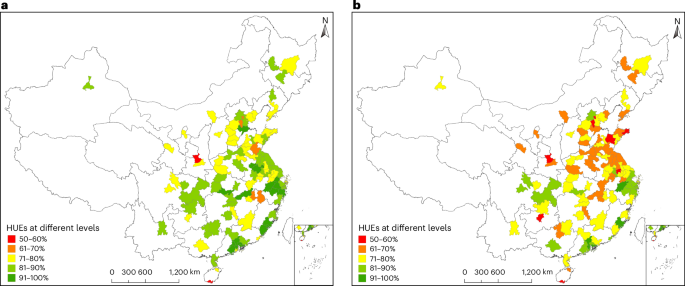

The phenomenon of 'ghost cities' in China represents an extreme form of (almost) complete vacancy in urban living spaces. In reality, however, the under-utilization of urban housing is far more common than complete vacancy, with many newly developed areas experiencing low occupancy rates or inefficient use (Figure 2). To date, there has been a lack of nationwide studies that examine the status and evolution of the discrepancy between urban housing supply and demand in China at a high spatial resolution.

Figure 2. A comparison of inefficient housing observed during the day and at night from the same perspective.

In this study, the researchers first proposed the concept of "housing utilization efficiency (HUE)" to assess urban housing supply and demand. HUE is defined as the ratio of the actual population to the population capacity within specific spatial units. Second, they developed a framework to measure HUEs across China for the years 2010 and 2020 at a high spatial resolution (sub-district level), utilizing various emerging big data sources. Third, they analyzed the spatio-temporal evolutions of China's urban HUEs between 2010 and 2020 at multiple scales, including the sub-district, city and region levels.

The findings of this study reveal that the overall HUE in China’s highly urbanized areas decreased from 84% in 2010 to 78% in 2020. The cities that experienced the highest decreases in HUEs between 2010 and 2020 were primarily concentrated in the northern part of the Yangtze River Delta and the Shandong Peninsula, with reductions generally ranging from 10% to 20%. Smaller cities, compared to larger ones, tended to experience more significant decreases in HUEs. Furthermore, it is surprising that the most notable decrease in average HUE at the intra-urban scale between 2010 and 2020 was observed in areas located in the central layer of the urbanized region.

The patterns and dynamics of HUEs across China between 2010 and 2020, as discovered by the researchers, are in relation to the country’s specific urbanization characteristics and policies. The motivation for urban construction in many local governments has been greatly stimulated by their heavy reliance on land transfer revenue for public finance over the past two decades, a phenomenon extensively documented and referred to as "land finance". Numerous urban housing complexes, commercial properties, industrial facilities and infrastructure were constructed on the urban peripheries accompanied by the development of these new towns and districts (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The very high-resolution satellite image and drone photograph illustrate the extensive construction of urban housing complexes on the urban peripheries.

Populating these new developments after construction became a major challenge for many local governments. The expected populations mainly come from two main sources: First, populations migrate from inner urban areas to these new developments at the urban peripheries for improving their housing conditions; and second, populations migrate from surrounding rural areas or some lower-tier cities in search of more opportunities. Thus, population loss was observed between 2010 and 2020 in the inner urban areas of many cities, but not throughout the entire city. Conversely, the population in the outer urban areas generally increased accompanied by extensive urban housing growth during the same period. Thus, this development is a result of the outward migration or relocation of downtown functions, accompanied by rural-urban migration.

On the other hand, the researchers observed that regions with notably low HUEs or significant decreases in HUEs between 2010 and 2020 were more likely to experience the 'ghost city' phenomenon. This indicates that some new developments have failed to attract enough residents, despite many of their properties having been purchased through pre-sales. As a result, they contributed to the emergence of the "ghost city" phenomenon. Low-tier cities located in eastern China suffered more from it, due to their large number of new developments but low attractiveness between 2010 and 2020.

The link of this research:

Follow the Topic

-

Nature Cities

This journal aims to deepen and integrate basic and applied understanding of the character and dynamics of cities, including their roles, impacts and influences — past, present and future.

Please sign in or register for FREE

If you are a registered user on Research Communities by Springer Nature, please sign in